Design Intelligence

Cf.

- Design Knowledge

- Design

- Intelligence

- Knowledge

- Information

- Bias

- Robustness

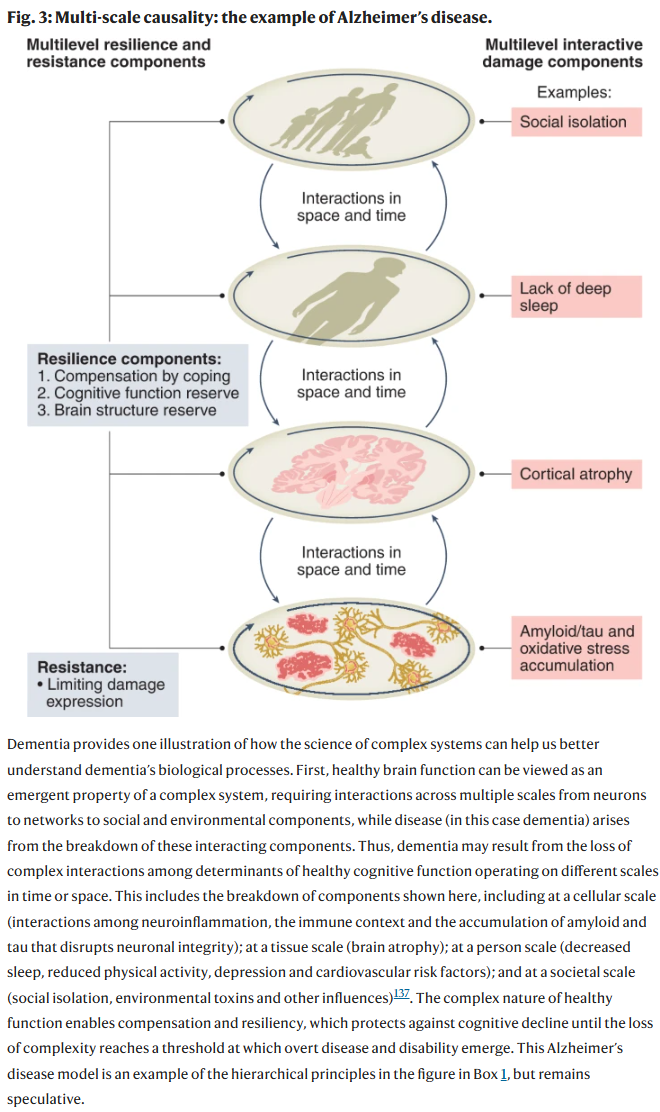

- Resilience as a concept, Resilience as an approach

- Leadership

- astrocognition

- technosignatures (intelligence as an ability to transmit electromagnetic signals)

- gradational intelligence (in all biological entities)

- robustness

- resilience

- response diversity

- viability theory

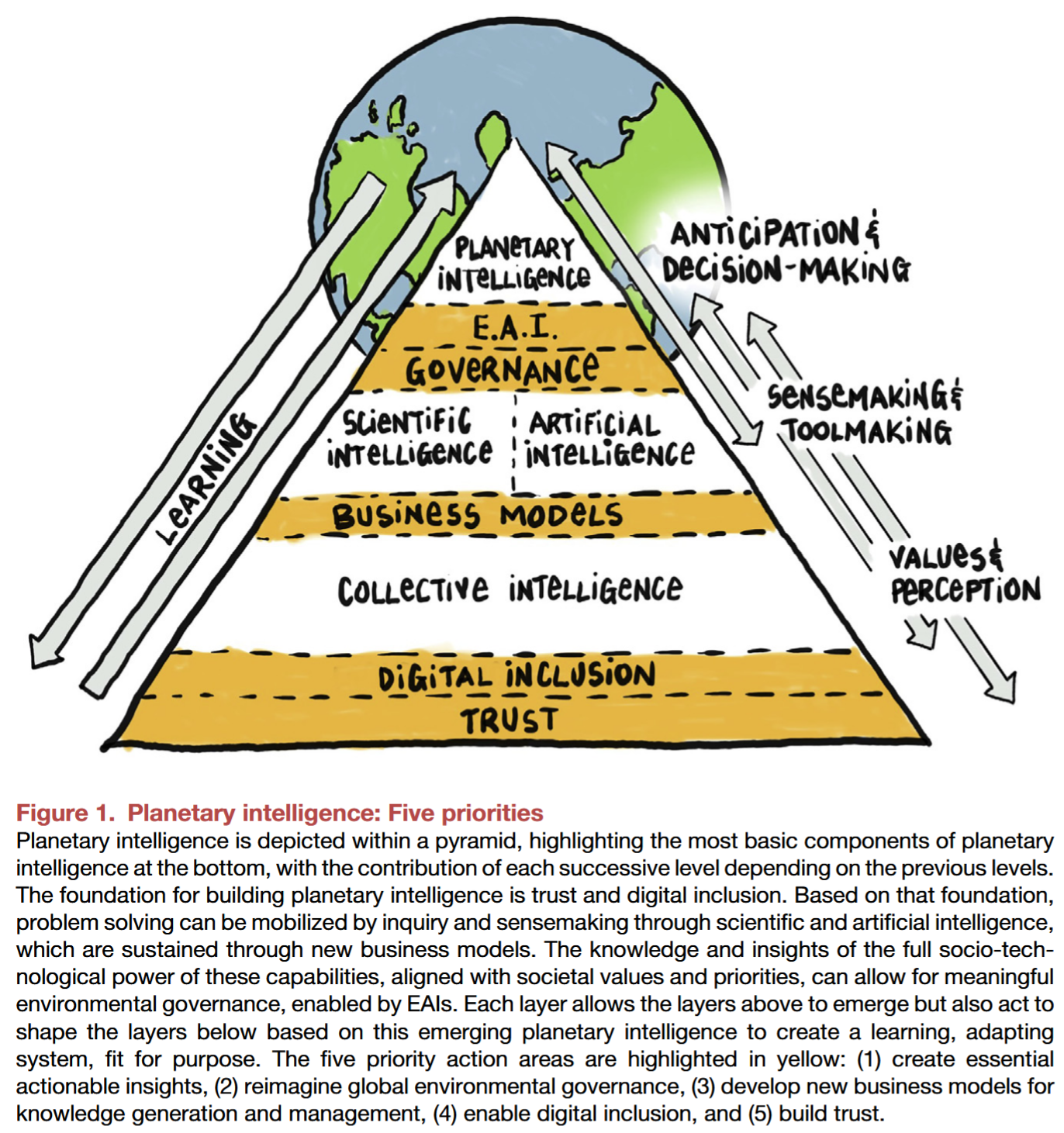

- planetary intelligence

Premises

TOC

- Ontological and epistemological framing of intelligence

- Definitions and mechanisms of intelligence

- Promises and advantages of intelligence

- Costs, risks, and trade-offs of intelligence

- Alternatives and complements to intelligence

- Amplifying, constraining, and designing with intelligence

Agents and Processes of Intelligence

- Individuals (organisms, devices)

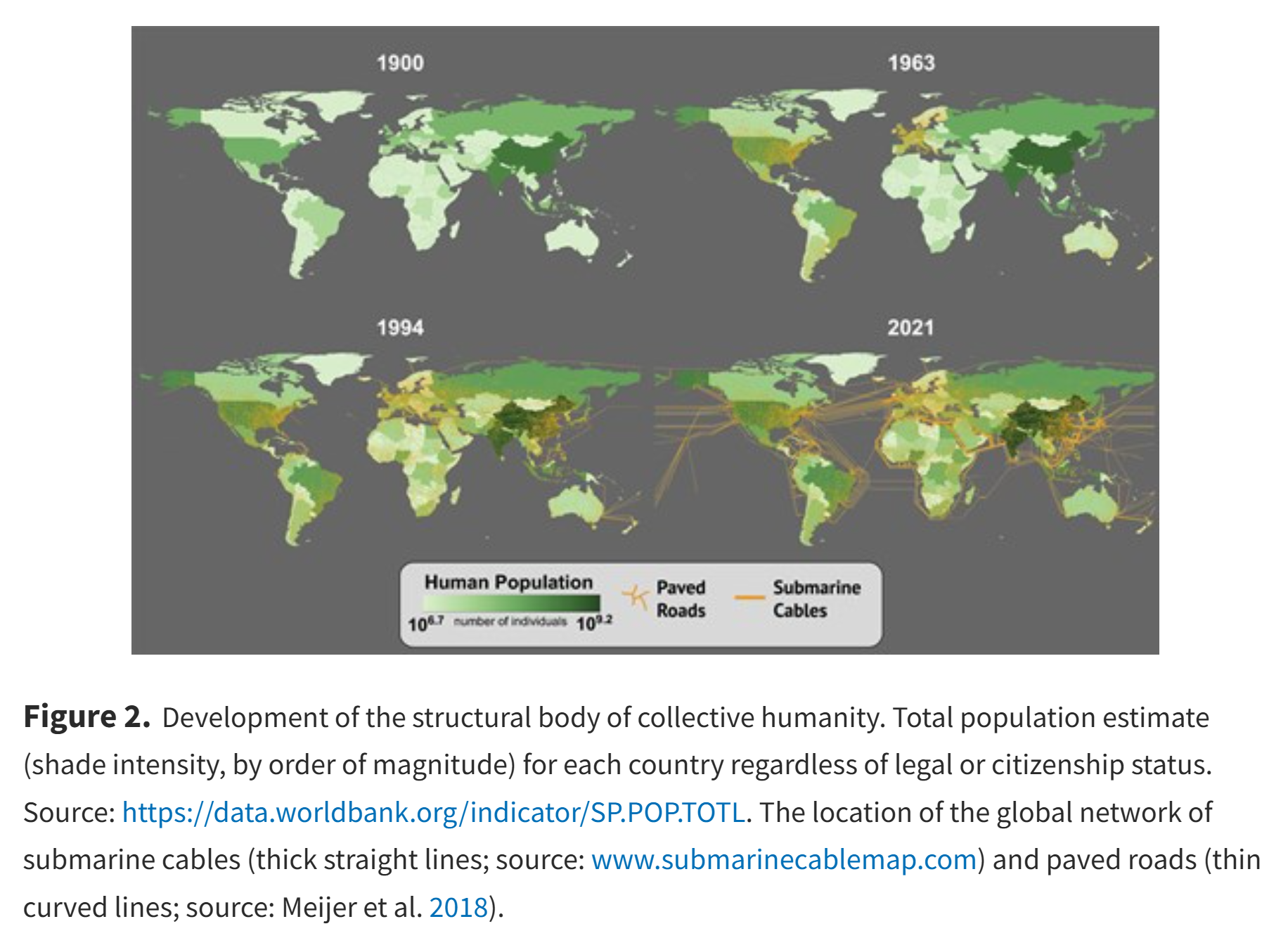

- Collectives (swarms, societies, ecosystems, planetary)

- Relationships (niches, environments, planetary systems)

- Processes (sensing, information processing, communication, decision-making, acting, learning, adaptation, evolution)

- Systems (biological, technological, socio-ecological, planetary)

- Regimes (legal, cultural, political)

Definitions and Mechanisms of Intelligence

See: Intelligence

Promises and Advantages of Intelligence

-

Intelligence is one of many evolved strategies for persistence in far‑from‑equilibrium, energy processing systems (cf. Life). It does not have a privileged status that makes it more valuable than other ways of being. Humans tend to valorise intelligence because it is their dominant survival strategy.

-

Intelligence emerges in specific ecological and evolutionary contexts. It is one strategy among others, such as faster reproduction, the production of more offspring or eggs, or more cautious life histories.

-

Intelligence deal with the identification of patterns and the making of decisions under conditions of limited information, knowledge, time, and resources. It aims at satisficing rather than optimality or perfection. It injects limited information, compresses it for processing, and compares incoming data with limited models produced through prior experimentation and tested through trial‑and‑error approaches that try to keep the whole chain economical.

-

Intelligence operates as insurance against uncertainty. Corvids, for example, hide food, spend resources to pretend to hide food, re‑cache if they think others observed them, and retrieve caches. This flexibility enables them to cope with unpredictable environments.

-

Intelligence is a strategy that societies and organisms co‑opt and repurpose in many different ways. The flexibility of intelligence allows misapplication at the same time as beneficial innovation. Its evolved characteristics were tactical. By contrast, humans (or rather collective systems that include humans?) can apply intelligence to pursue curiosity about the world, to play, or to serve diverse purposes that humans invent. Cf. the discourse about civilisational paths in astrobiology.

-

Intelligence is paradoxical. Its operation must be agile, short term, and limited in scope, but its results presume longevity. Longevity is necessary for learning and training and for time to benefit from the application of intelligence. In organisms, this often means longer lifespans, such as those of whales, elephants, or sharks, with extended periods of care. Longevity can also arise from the societal retention of knowledge, culture, and technology across generations.

Costs and Trades-offs of Intelligence

-

Organisms use heuristics and bounded rationality, combined with adaptive forgetting and other strategies, to limit these costs. Even death evolved as an adaptive strategy that limits the costs of intelligence by resetting, error correcting and updating in a cheaper way (it is also a boundary for complexity in organism design, programmed death at cell levels is a way to improve signal-to-noise ratio by pruning neurones, etc.). Retention of useful information while purging what is not useful is the key challenge for this approach. A challenge of selecting usefulness is constant. Biological systems and human waste circumvent it by accepting extinctions and redundancies in a world that local agents see as unbounded.

-

Gathering, processing, storing, retrieving, updating, and testing information is costly. The human brain is an expensive tissue. Human lifestyle, geographical distribution, social structures, and diets all had to change to sustain it. The impact is even more dramatic when societies prioritise certain desired properties of collective and technologically supported intelligence. Greater intelligence requires a greater energetic budget and has further implications.

-

Intelligence is not always the best or only strategy. Humans often overfit their predictive models and misallocate resources. Nonhuman beings can also overspend on intelligence (cf. ecology of fear). For instance, corvid caching behaviour can incur substantial opportunity costs, especially when they forget where they hid food. In such cases, the premiums of intelligence as insurance against uncertainty become unsustainable or counterproductive.

-

Externalisation into collectives changes the economy of intelligence. Less biological computation is required per individual, but the system must invest in the maintenance of artefacts and institutions.

-

Long‑lived intelligence systems can generate slow crises. Climate change, driven by energy‑intensive technologies that earlier generations deployed for short‑term gains, is a prime example. In this frame, efforts such as the slow food movement may appear as local self‑indulgence in the face of larger systemic issues.

-

The same flexibility makes intelligence dangerous. It often leads to traps, problems, and misjudgements when people apply it outside its original evolutionary frame. So, not only costly but with a negative reward for survivability at the expense of curiosity or creativity.

-

Intelligence might appear to be innovative, but it is always path dependent and constrained by prior investments, existing structures, and resources. At the individual and institutional level, sunk‑cost effects mean that agents continue to invest in failing strategies because they have already committed resources. Technological systems of artificial intelligence can exhibit capability overhangs when actors repurpose them beyond their design assumptions, which creates new vulnerabilities.

Alternatives and Complements to Intelligence

See: Robustness

-

Intelligence is one strategy among many. Other strategies, such as faster reproduction, high fecundity, or more cautious life histories, can support persistence without substantial investment in information processing.

-

Robustness, redundancy, and apparent “inefficiency” can have evolutionary advantages. The configurations that persist in living systems are rarely the most efficient in human engineering terms. Instead, they can absorb shocks, maintain functional variability, sustain redundancy, and cope with novelty while combining agility with slowness.

-

Robustness and intelligence co‑evolve. Systems that can tolerate errors and variability are better able to explore and learn, because components can become damaged, disconnect, or die, while the system persists. At the same time, robustness often requires intelligent strategies such as feedback loops, modularity, and degeneracy.

-

Niche construction provides another alternative or complement. Organisms increase robustness by constructing niches that reduce environmental uncertainty. Intelligent agents build niches to increase robustness. Stable niches allow exploration and learning and can foster higher intelligence. Environmental engineering reduces stress and risk and can enable complex behaviour, but it can also reduce the need for intensive internal computation by stabilising the environment.

-

In the frame of viability theory, living systems do not maximise a scalar objective. They remain within acceptable states across time and perturbation. Intelligence is self‑evidencing and maintains an agent’s existence within its ecological niche, but it operates alongside other strategies that sustain viability.

Amplifying, Constraining, and Designing with Intelligence

To be developed...

- Amplify by coupling agents into larger sensing–acting ensembles.

- Use automation to concentrate and distribute intelligence, changing who or what counts as an intelligent agent.

- Prospect for nonhuman proposals.

AI Related Considerations

- Algorithmic conservation (e.g., digital forests, twins, etc.)

- Smart more-than-human cities and urban governance

- Hybrid human-nonhuman-AI decision-making collaborations

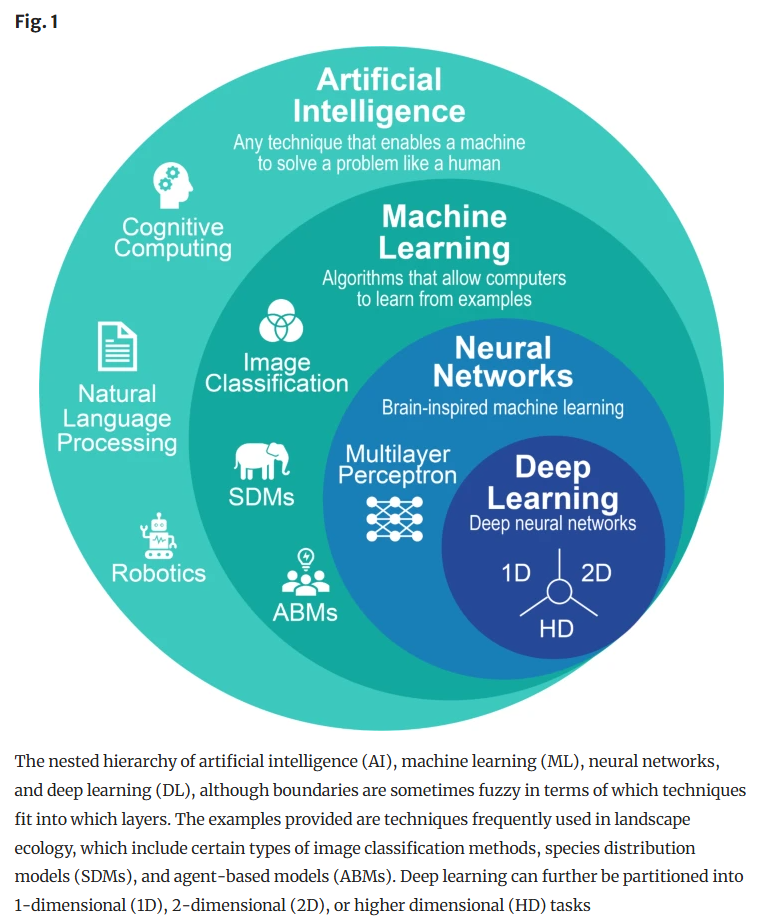

This is a not unproblematic taxonomy that is technique-centric and mixes domains with methods.

Frazier, Amy E., and Lei Song. “Artificial Intelligence in Landscape Ecology: Recent Advances, Perspectives, and Opportunities.” Current Landscape Ecology Reports 10, no. 1 (2024): 1. https://doi.org/10/hbb6wb.

Han, Barbara A., Kush R. Varshney, Shannon LaDeau, Ajit Subramaniam, Kathleen C. Weathers, and Jacob Zwart. “A Synergistic Future for AI and Ecology.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 38 (2023): e2220283120. https://doi.org/10/gsrsmr.

This is a Microsoft paper.

Luers, Amy L. “Planetary Intelligence for Sustainability in the Digital Age: Five Priorities.” One Earth 4, no. 6 (2021): 772–75. https://doi.org/10/gpx3bq.

Kloppenburg, Sanneke, Aarti Gupta, Sake R. L. Kruk, Stavros Makris, Robert Bergsvik, Paulan Korenhof, Helena Solman, and Hilde M. Toonen. “Scrutinizing Environmental Governance in a Digital Age: New Ways of Seeing, Participating, and Intervening.” One Earth 5, no. 3 (2022): 232–41. https://doi.org/10/gp8hq6.

Francisco, Marie, and Björn-Ola Linnér. “AI and the Governance of Sustainable Development. An Idea Analysis of the European Union, the United Nations, and the World Economic Forum.” Environmental Science & Policy 150 (2023): 103590. https://doi.org/10/gsshn7.

Principles and Approach

Consider system-like process-based characteristics to assess living communities. Cf. development, plasticity, ageing, stress, etc.

Precedents and Subthemes

- Distributed and collective intelligence across scales.

- Materiality of intelligence as a distributed resource-intensive system.

- Intelligent studies, critical intelligence studies, governance and politics of intelligence.

Challenges and Needs

Roudavski, Stanislav. “The Ladder of More-than-Human Participation: A Framework for Inclusive Design.” Cultural Science 14, no. 1 (2024): 110–19. https://doi.org/10/g8nn27.

- Communication across diverse more-than-human collectives.

- Resisting biases in collective intelligence.

- Decision-making within these collectives.

- Understanding outcome and deciding on criteria of success.

- Sustaining effort over long timeframes.

- Responding in real time.

- Looking into history to understand system dynamics.

Argument Plan

Follow the AND, BUT, THEREFORE structure.

Objective

Frame a research agenda for design intelligence.

Significance

Without such a framework, both boosterish and critical narratives will remain anthropocentric and constrained by inherently biased and incomplete human intuitions.

Anthropocentric narratives, constrained by human biases and limited knowledge, impede transformative planetary change.

Cf.

Artificial Sociality Manifesto

Gaps

Existing definitions of intelligence lack ecological and evolutionary context, limiting their applicability to planetary-scale systems.

Substantial bodies of knowledge, practices, and future options remain unexplored because of the absence of methods to deploy more-than-human intelligence.

Research Question

Can design outcomes (expressed as an increase in the probability of thriving and justice) improve through application of an ecological and evolutionary framework for intelligence?

- Under what ecological and evolutionary conditions does intensifying design intelligence (in human, nonhuman, and artificial forms) increase or decrease the probability of multispecies thriving and justice?

- How can participatory design practices recognise, enlist, and redistribute more‑than‑human forms of intelligence (e.g. plant behaviour, ecosystem feedbacks, planetary signals)?

- Which alternative strategies (robustness, redundancy, niche construction, simplification, restraint) should designers sometimes prioritise over “more intelligence”?

Methods

- Conceptual synthesis. Integrate narratives of intelligence.

- Strategic comparison. Intelligence versus alternative strategies.

- Case studies. Reread cases from existing work (Where did intelligence reside? What trade-offs occurred?).

- Design principles and prompts (were does intelligence reside and what does it cost? Which nonhuman intelligences are already in action and how can they be amplified without exploitation? Would adding more sensing or predictive analytics increase or decrease thriving and justice in a given context?) Present as practical prompts.

Results

An ecological definition of intelligence within planetary systems (and beyond).

Alternative strategies with worthy goals and support for them.

An argument for the cases when intelligence is justified.

The costs and risks of the intelligence strategy.

Discussion

- Need for substrate-agnostic intelligence systems.

- Need for just intelligence systems (inclusion, transparency, accountability).

- Need for both amplified innovation and caution (bounded testing, cross-checking, delegation-first approaches, etc.).

Practical action.

Future research.

Conclusion

- AND: Design already participates in building multi‑scalar intelligences (local, institutional, planetary).

- BUT: Without a more‑than‑human framing, these intelligences risk being brittle, unjust, and ultimately self‑defeating. They also fail to access the full possibility space of alternative futures.

- THEREFORE: Designers need a concept of design intelligence that foregrounds trade-offs, costs, and long‑term viability sometimes recommending restraint rather than intensification.

References

This is an opportunistic selection for now.

Intelligence is the acquisition and application of collective knowledge operating at a planetary scale, integrated into the function of coupled planetary systems.

Frank, Adam, David Grinspoon, and Sara Walker. 2022. “Intelligence as a Planetary Scale Process.” International Journal of Astrobiology 21 (2): 47–61. https://doi.org/10/gphj4k.

Intelligence is the capacity to accumulate evidence for a generative model of one’s sensed world, or self-evidencing.

Friston, Karl J., Maxwell J. D. Ramstead, Alex B. Kiefer, Alexander Tschantz, Christopher L. Buckley, Mahault Albarracin, Riddhi J. Pitliya, et al. 2024. “Designing Ecosystems of Intelligence from First Principles.” Collective Intelligence 3 (1): 26339137231222481. https://doi.org/10/hbbnnz.

Information Framework of Intelligence (IFI) applies across all systems including physics, biology, humans and AI. Central to this framework is the “intelligence niche”, which provides a conceptual basis for understanding constraints on intelligence and the evolution of intelligence.

Hochberg, Michael E. 2025. “An Information Framework of Intelligence.” BioSystems 256: 105548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2025.105548.

General.

Clark, Andy. 2024. “Mind Unlimited?” In Extreme Philosophy: Bold Ideas and a Spirit of Progress, edited by Stephen Hetherington, 123–37. New York: Routledge.

A suggestive discussion of a relevant process (aging) from a complex systems perspective. Cf. also Stress

Cohen, Alan A., Luigi Ferrucci, Tamàs Fülöp, Dominique Gravel, Nan Hao, Andres Kriete, Morgan E. Levine, et al. “A Complex Systems Approach to Aging Biology.” Nature Aging 2, no. 7 (2022): 580–91. https://doi.org/10/gqqz7x.

Jacob, Michael S. 2023. “Toward a Bio-Organon: A Model of Interdependence between Energy, Information and Knowledge in Living Systems.” Biosystems 230: 104939. https://doi.org/10/hbbnsr.

Jacob, Michael, and Parham Pourdavood. 2025. “Evolutionary Principles Shape the Health of Humanity as a Planetary-Scale Organism.” BioScience, 2025, biaf055. https://doi.org/10/hbbnsx.

Finkenstadt, Daniel J. 2025. Bioinspired Strategic Design Nature-Inspired Principles for Dynamic Business Environments. New York: Routledge.

Korteling, J. E. (Hans), Geke C. van de Boer-Visschedijk, Romy a. M. Blankendaal, Rudy C. Boonekamp, and Aletta R. Eikelboom. 2021. “Human- versus Artificial Intelligence.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 4: 622364. https://doi.org/10/gjrvcx.

Lingam, Manasvi, Adam Frank, and Amedeo Balbi. 2023. “Planetary Scale Information Transmission in the Biosphere and Technosphere: Limits and Evolution.” Life 13 (9): 1850. https://doi.org/10/gstc3n.

Lior, Yair, and Patrick McNamara. 2025. “Major Evolutionary Transitions in Culture and Cognition: The Anthropocene and Techno-Biotic Cognition.” Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences (US), 2025, 1–28. https://doi.org/10/hbbnn5.

Wong, Michael L., and Anirudh Prabhu. 2023. “Cells as the First Data Scientists.” Journal of The Royal Society Interface 20 (199): 20220810. https://doi.org/10/gr542v.

Scharf, Caleb, and Olaf Witkowski. 2024. “Rebuilding the Habitable Zone from the Bottom up with Computational Zones.” Astrobiology 24 (6): 613–27. https://doi.org/10/gt7gqp.

Tegmark, Max. 2017. Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Trewavas, Anthony. 2014. Plant Behaviour and Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.