Leadership

This note is about the concept of leadership, especially collective and more-than-human versions of the concept.

Cf.

- Knowledge

- Agency

- Governance

- stewardship

- trusteeship

- custodianship

- control

- influence

- organizing

- coordination

- guidance

- authority

- power

- responsibility

- Decision Making

- quorum sensing

- collective decision-making

- intergroup conflict1, intergroup cooperation

- collective knowledge2

Definitions

Anthropocentric

“a co-created, performative, contextual, and attributional process where the ideas articulated in talk or action are recognized by others as progressing tasks that are important to them”3

Types of leadership:

- Leadership as position: does where leaders operate make them leaders?

- Leadership as person: do the qualities or identities of leaders make them leaders?

- Leadership as result: do the outcomes leaders achieve make them leaders?

- Leadership as process: does how leaders get things done make them leaders?

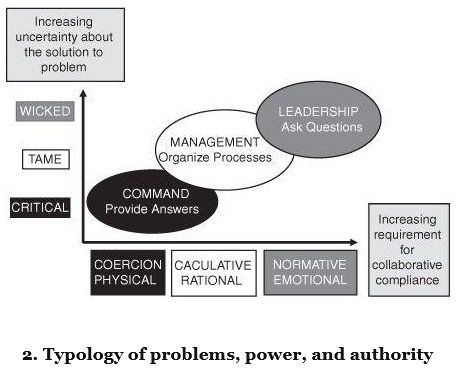

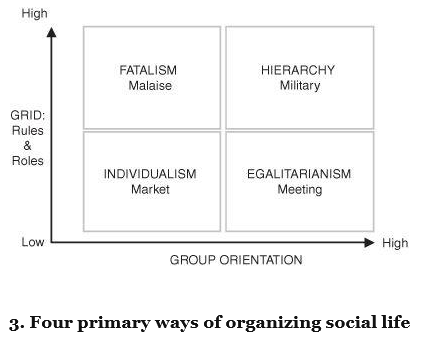

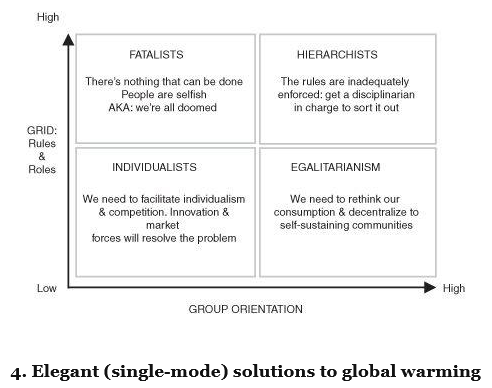

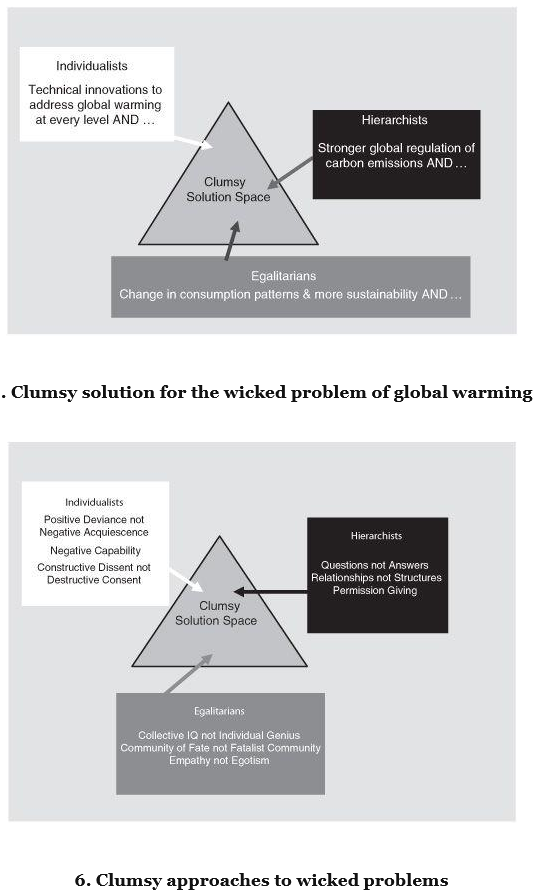

"Elegant" solutions are problematic. Instead, multiple frameworks overlap in practice creating a "clumsy solution space".

How would these diagrams and frameworks change in the context of "naturalised", more-than-human leadership?

Grint, Keith. Leadership: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Intermediate Perspectives

These are perspectives that might be anthropocentric but that are also opening possibilities that can result in a foundation for more-than-human or nonhuman leadership.

Emotion

There is research on Emotion or valency in all lifeforms. This can link to the discussion of emotion in leadership.

Lonati, Sirio, Zachary H. Garfield, Nicolas Bastardoz, and Christopher von Rueden. “Leadership as an Emotional Process: An Evolutionarily Informed Perspective.” The Oxford Handbook of Evolution and the Emotions (Oxford), 2024, 1021–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197544754.013.33.

Marginal Human Cases such as Infants

As an example of marginal cases that can apply to rights but also to leadership. This can include young children, people with severe cognitive disabilities, and other humans who are not typically considered capable of leadership. This can help us understand the minimal conditions for leadership and how it might apply to nonhuman animals or collectives such as ecosystems.

Margoni, Francesco, and Lotte Thomsen. “How Infants Predict Respect-Based Power.” Cognitive Psychology 152 (2024): 101671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2024.101671.

Inclusive

How can we define leadership in non-anthropocentric way?

Leadership is a relationship between agents that influences choice making in action selection.

Leadership is:

- What mechanisms/events control/influence the action/process first (set the schedule, set the budget as per usual, or ensure survival of old trees or habitat retention first, etc.)

- The adjustment of the slope of probability towards a goal or a tendency

- A reward or lure for directed actions

Leadership is not:

- Not tyranny or absolute control

Leadership is a collective phenomenon. It presumes a group with a freedom to chose and the choices that follow some agents rather than others.

Leadership involves subjective risk taking. If there is an evolved preference or some other imposed mechanism, it is not leadership. This does not imply consciousness or self-awareness.

The leader does not need to chose or commit to leadership to lead.

Leadership involves some form of credit from the followers who take risk in following without complete knowledge of the outcomes.

Leadership can result in multiple forms of benefit, not only in the attainment of a goal.

Leadership has persistence across multiple decisions and tolerance towards variable outcomes.

Relational leadership: socially constructed, processual, and emerging.

Uhl-Bien, Mary. ‘Relational Leadership Theory: Exploring the Social Processes of Leadership and Organizing’. The Leadership Quarterly 17, no. 6 (2006): 654–76. https://doi.org/10/dfhbrh.

Evolutionary Perspectives

A more general process to leadership is the process of hierarchy formation in groups. This still focuses on the evolution of human leadership largely skipping at fast speed the pre-human evolution is biasing the discussion towards human and human-like leadership. A very hierarchical approach too that presumes progress and human technical systems at the pinnacle.

Cf. special issues “The evolution and biology of leadership: A new synthesis” in The Leadership Quarterly (2020).

Van Vugt, Mark, and Christopher R. von Rueden. “From Genes to Minds to Cultures: Evolutionary Approaches to Leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 2 (2020): 101404. https://doi.org/10/ggqh4n.

Little, John C., Roope O. Kaaronen, Janne I. Hukkinen, Shuhai Xiao, Tatyana Sharpee, Amro M. Farid, Roshanak Nilchiani, and C. Michael Barton. “Earth Systems to Anthropocene Systems: An Evolutionary, System-of-Systems, Convergence Paradigm for Interdependent Societal Challenges.” Environmental Science & Technology 57, no. 14 (2023): 5504–20. https://doi.org/10/gzz84q.

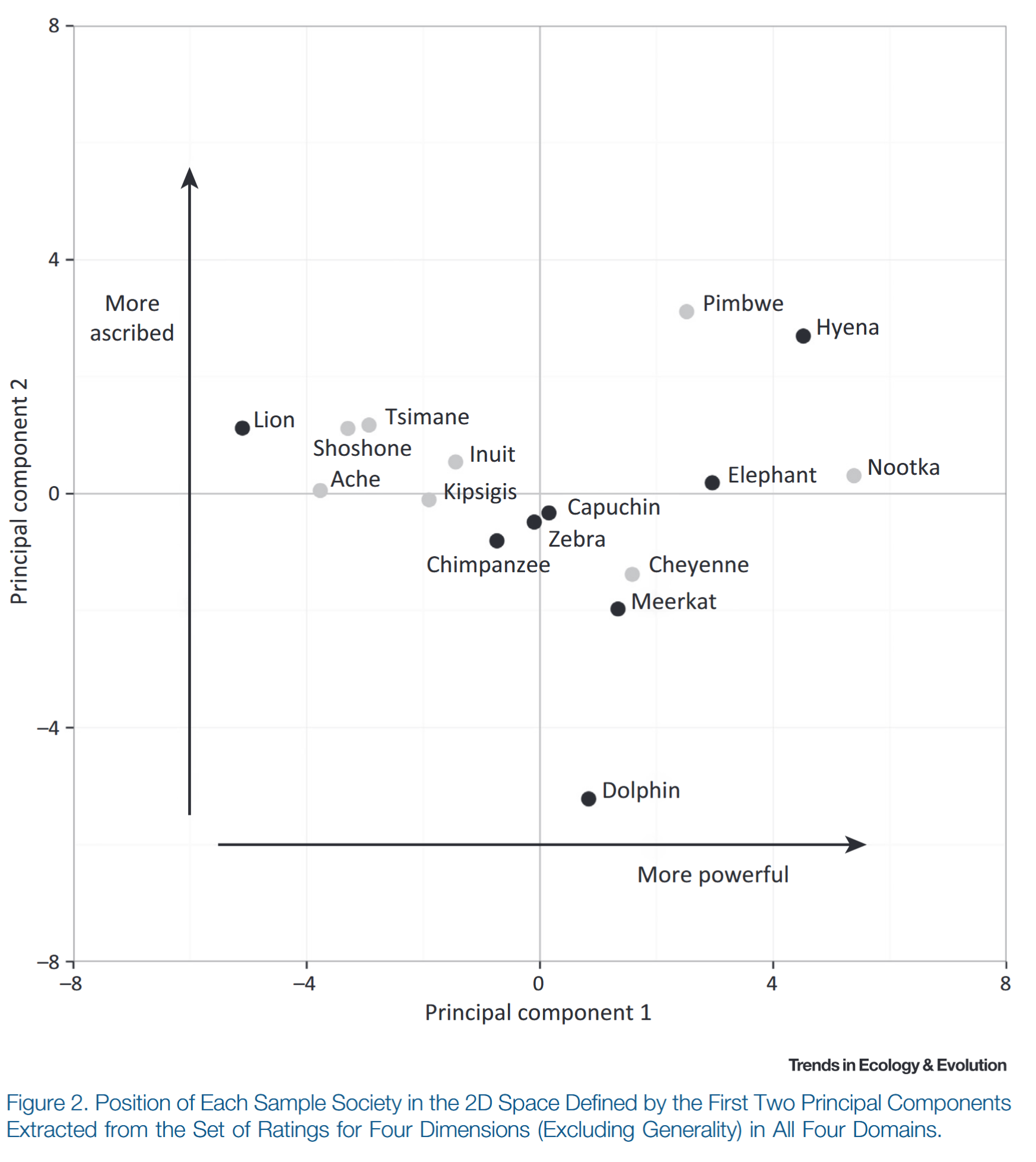

"Variation in leadership can be measured in multiple dimensions, including emergence (how does one become a leader?), distribution (how widely shared is leadership?), power (how much power do leaders wield over followers?), relative benefit (do leaders gain more or less than followers?), and generality (how likely are leaders in one domain, such as movement or conflict resolution, to lead in other domains?).

A comparative framework based on these dimensions can reveal commonalities and differences among leaders in mammalian societies, including human societies."

Smith, Jennifer E., Sergey Gavrilets, Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, Paul L. Hooper, Claire El Mouden, Daniel Nettle, Christoph Hauert, et al. “Leadership in Mammalian Societies: Emergence, Distribution, Power, and Payoff.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 31, no. 1 (2016): 54–66. https://doi.org/10/f77f6h.

Emergent Perspectives

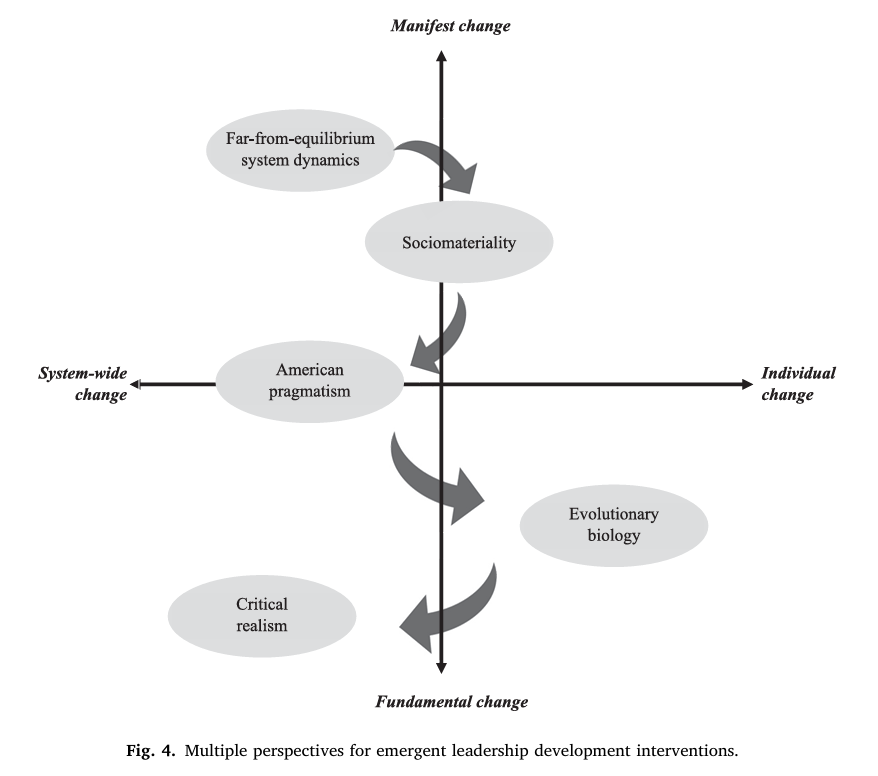

A review of perspectives on emergent leadership.

Wolfram Cox, Julie, Karryna Madison, and Nathan Eva. “Revisiting Emergence in Emergent Leadership: An Integrative, Multi-Perspective Review.” The Leadership Quarterly 33, no. 1 (2022): 101579. https://doi.org/10/gpd6rr.

Information Perspective

Leadership can be defined as the process by which certain agents in a system disproportionately influence the information flows that shape collective decision-making and action selection.

In Human Organizations/Systems

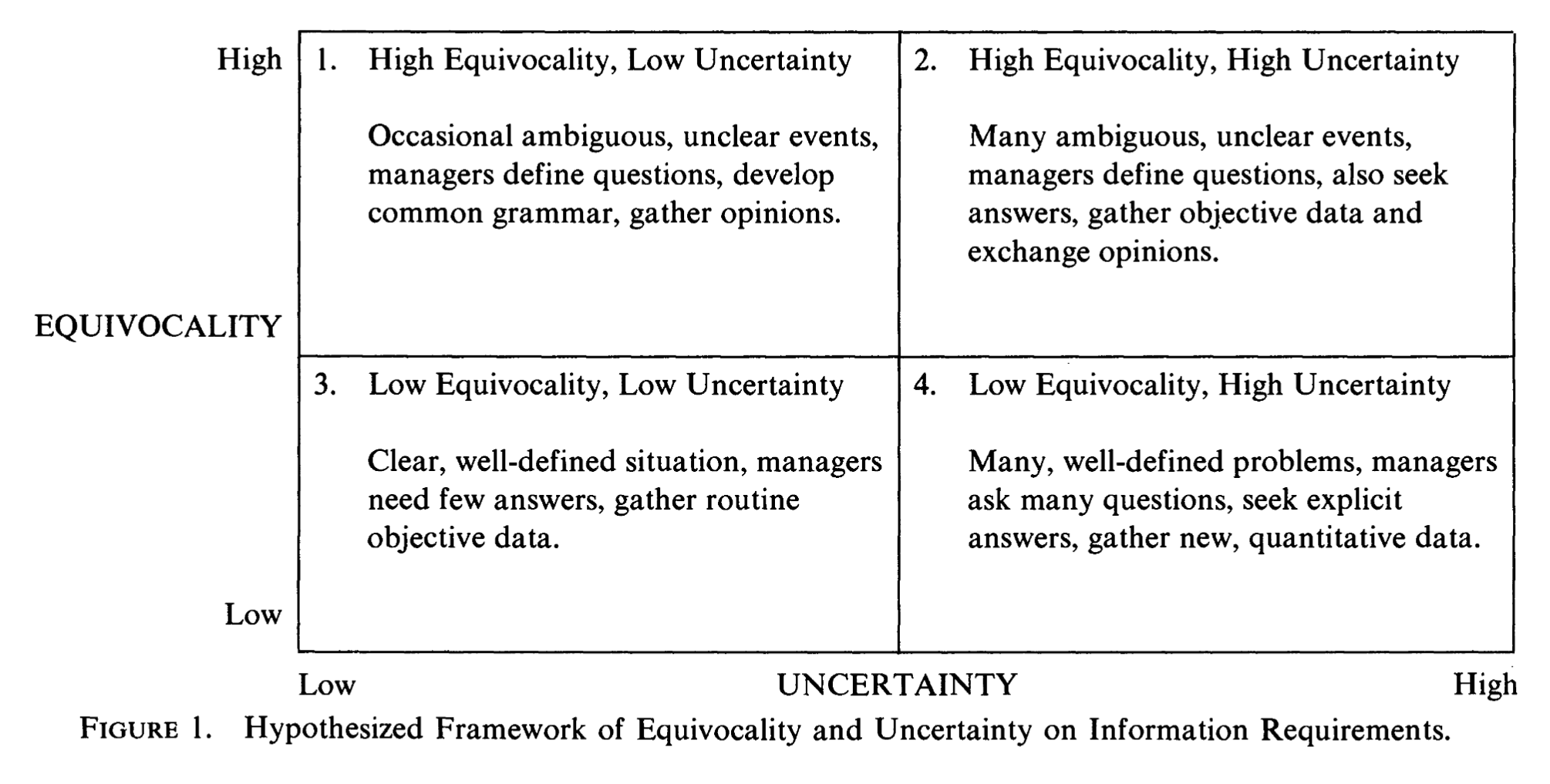

Organizational structures exist to process/transform information under uncertainty.28 Cf. the “information-processing view” of organisation design (rules, hierarchy, lateral relations) as ways to reduce/handle uncertainty and reduce information burdens.29

Daft, Richard L., and Robert H. Lengel. “Organizational Information Requirements, Media Richness and Structural Design.” Management Science 32, no. 5 (May 1986): 554–71. https://doi.org/10/dhd6jr.

Arrow, Kenneth Joseph. The Limits of Organization. New York: Norton, 1974.

Economic/information constraints on coordination; useful for framing leadership as reducing coordination costs by simplifying decisions/communications.

Sensemaking as Meaning Compression

Cf.

- sensemaking

- sensegiving

- sensebreaking

- narrative leadership

The function of leaders is to turn ambiguity into a coherent story that can guide action.

Weick, Karl E. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2010.

Maitlis, Sally, and Marlys Christianson. “Sensemaking in Organizations: Taking Stock and Moving Forward.” Academy of Management Annals 8, no. 1 (2014): 57–125. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.873177.

Attention as a Limited Resource

Leaders and leadership structures allocate limited attention, effectively compressing the information the organization interprets as salient.

Ocasio, William. “Towards an Attention-Based View of the Firm.” Strategic Management Journal 18, no. S1 (1997): 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199707)18:1+%253C187::AID-SMJ936%253E3.0.CO;2-K.

In Nonhuman/Ecological Systems

Stigmergy (environment as a compressed message), where ant pheromone trails compress private foraging experiences into a scalar value (“trail strength”) that biases routing.

Bonabeau, Eric, Marco Dorigo, and Guy Theraulaz. Swarm Intelligence: From Natural to Artificial Systems. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Hölldobler, Bert, and Edward O. Wilson. The Ants. Berlin: Springer, 1990.

Quorum thresholds (one bit: go / no-go), groups compress distributed evidence into a threshold crossing that triggers a phase transition (honeybees selecting sites, bacterial quorum sensing where molecules encode population density and behaviour switches at thresholds).

Seeley, Thomas D. Honeybee Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Waters, Christopher M., and Bonnie L. Bassler. “Quorum Sensing: Cell-to-Cell Communication in Bacteria.” Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 21, no. 2005 (2005): 319–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001.

Challenges

Leadership in the Anthropocene must respond to interconnected ecological and social crises (a polycrisis) driven largely by intensive human (especially capitalist) activity. This requires moving beyond strictly anthropocentric models toward ecocentric, relational, and systems‑thinking frameworks that:

- recognise multispecies agency and biophysical limits,

- prioritise long‑term collective stewardship and precaution over short‑term control,

- aim for regenerative rather than exploitative outcomes,

- distribute influence and accountability across human and nonhuman actors and institutions,

- integrate diverse knowledges (scientific, Indigenous, local), and

- enable adaptive, equity‑centred decision‑making across scales.

In practice, this reframes leadership as an ongoing, situated process of coordinating care, resilience, and justice across socio‑ecological systems rather than as command by isolated individuals.

Still most of existing approaches would argue for stewardship and responsible guardianship by humans for future human generations.

DDL Definition (working)

Roudavski, Stanislav. “Design for All Life: Editorial.” Architect Victoria 3 (2022): 32–37. https://doi.org/10/gr3r7f.

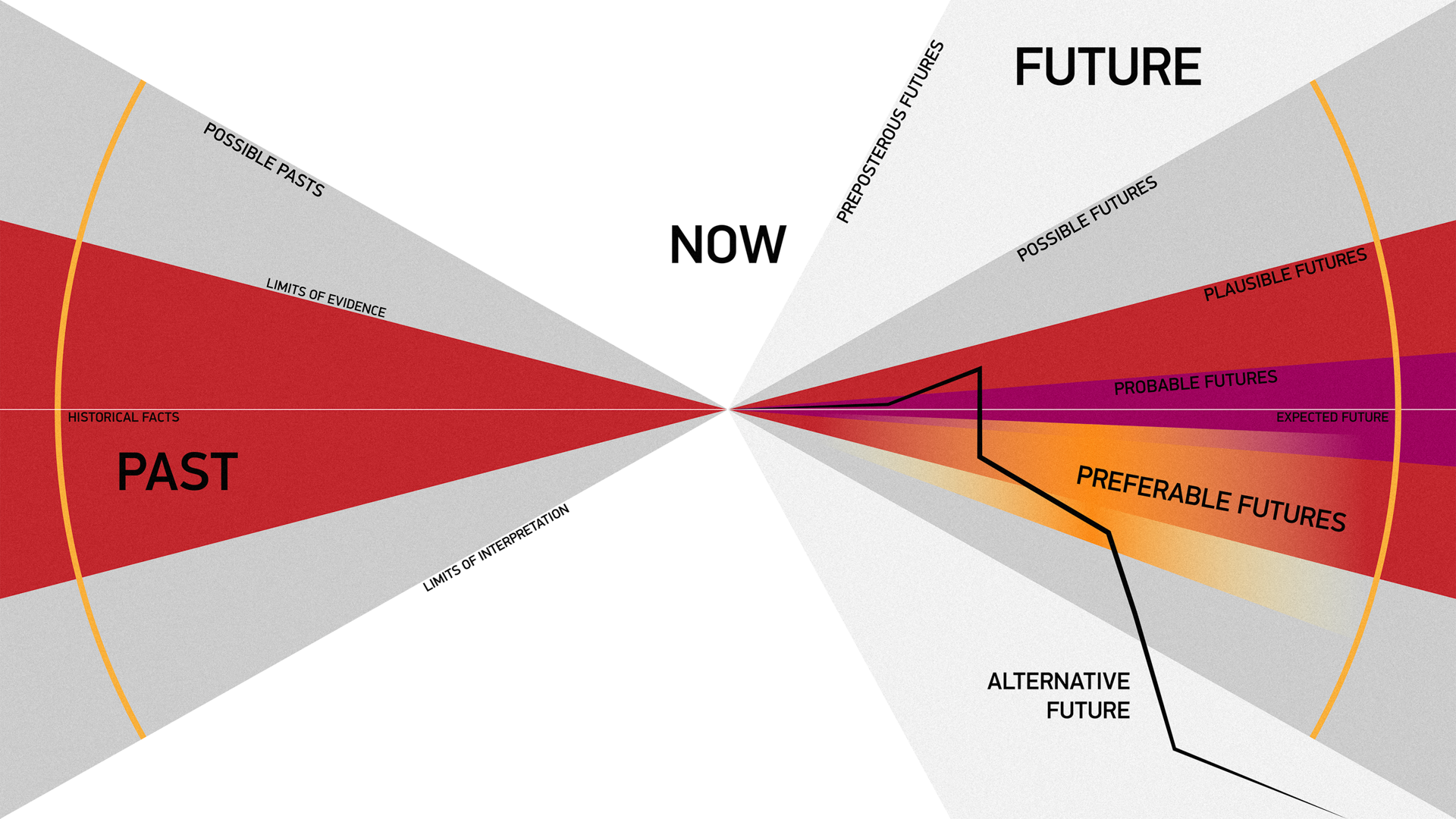

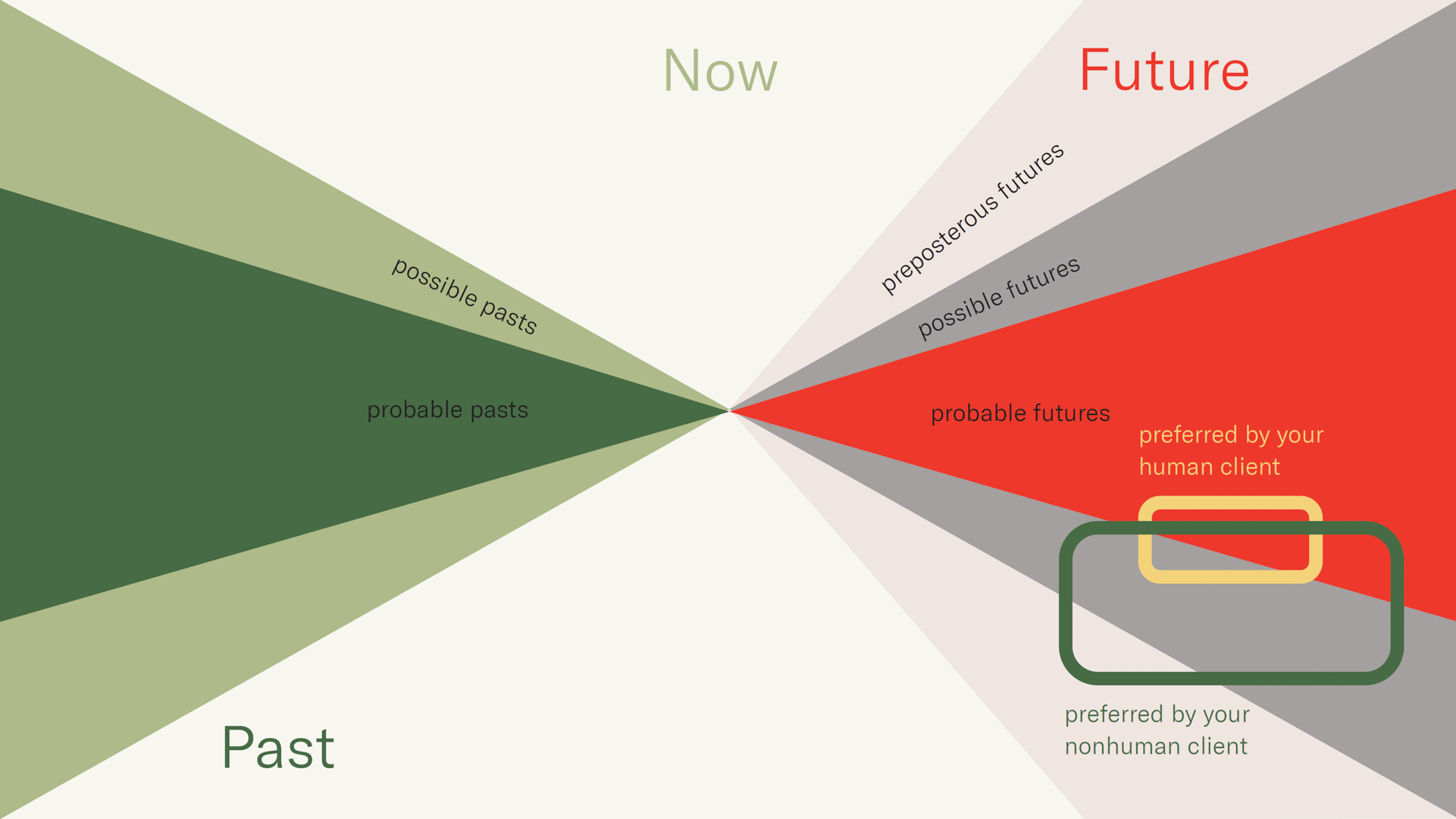

Leadership is a force that results in a redirection of the trends towards some preferable futures. It is opposite to resistance to such redirection. Each redirection requires effort.

Background

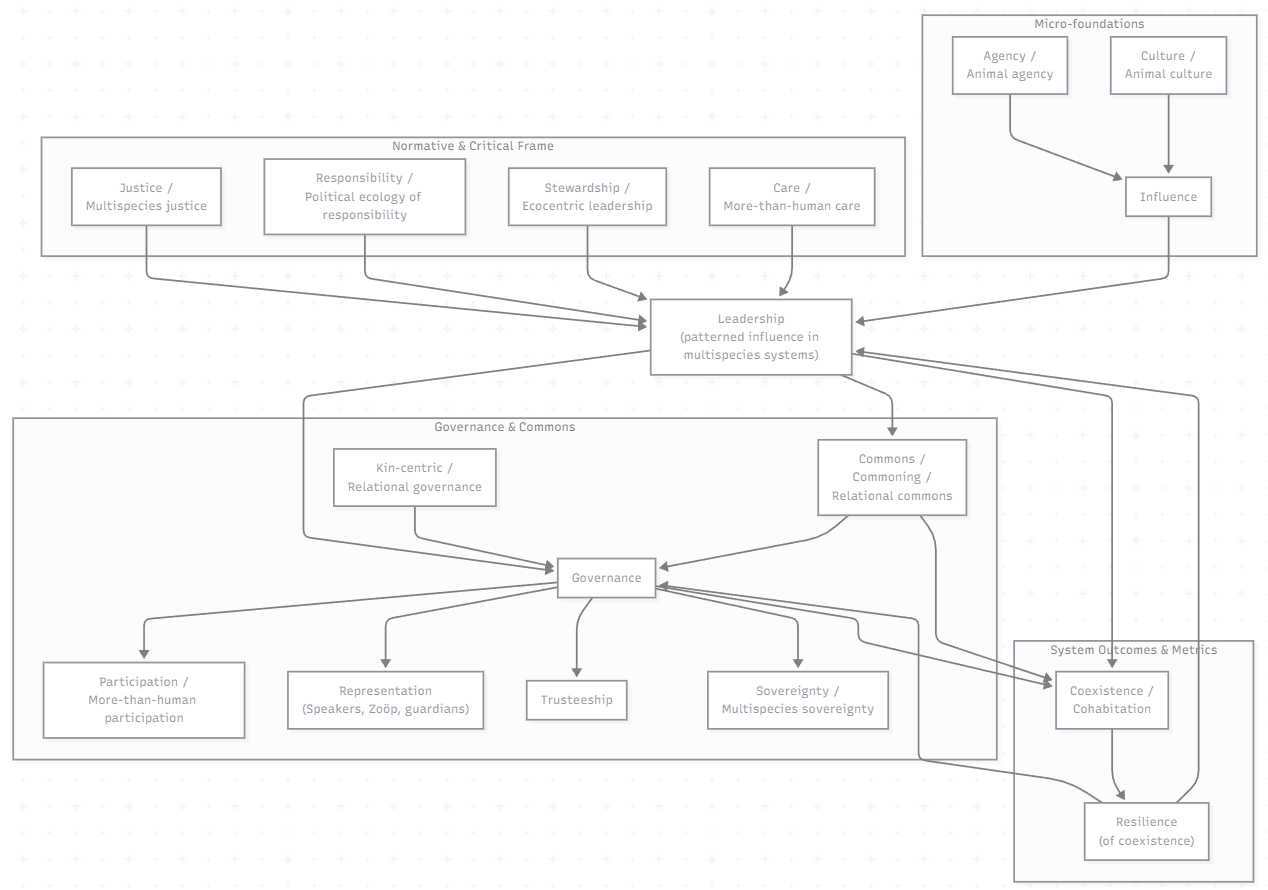

- There is empirically grounded scholarship showing:

- Nonhuman animals and ecosystems exert systematic, often decisive influence on socio‑ecological trajectories (animal agency/culture, cooperative foraging, place‑making, hydrosocial processes).

- Governance and commons theory increasingly centres relations, interdependence, care, and multispecies justice rather than human control over “resources”.

- Design, architecture, and HCI are experimenting with methods, artifacts, and infrastructures that decentre humans and treat nonhuman beings and ecological processes as clients, co‑designers, or rights‑bearing stakeholders.

- Only a few works link these strands to “leadership” per se, but several provide bridges:

- Animal agency and culture as measurable influences on management outcomes and collective behaviour.

- Relational commons and multispecies organizing as governance frameworks where influence is distributed across species and processes.

- Ecocentric leadership and coexistence resilience as governance concepts that are related to leadership.

- There is no single framework of non-anthropocentric leadership.

Processes, Functions, and Mechanisms

- Influence

- Coordination

- Facilitation

- Brokerage

- Boundary spanning

- Mobilisation

- Convenorship

- Legitimacy

- Attribution/credit

- Trust dynamics

Key Approaches

Leadership as Practice

Why this counts as leadership (practice) and not just mutual influence?

-

Leadership as practice names a patterned, directional form of influence that coordinates collective action toward shared or emergent ends; by contrast, mutual influence can be symmetric, transient, and uncoordinated.

-

Key distinguishing features:

- Directionality/asymmetry: practices systematically bias decision‑making or action selection in particular directions (scheduling, prioritising, cueing), not merely produce reciprocal effects.

- Coordination function: practices align timing, roles, information, and resources so participants pursue coherent joint outcomes.

- Persistence and patterning: leadership appears as recurring routines, norms, signals, or skill distributions that persist across multiple decisions.

- Risk and credit dynamics: following involves contingent risk; leadership practices include mechanisms for attribution, trust, or legitimacy that make risky following possible.

- Enabling capacity: leadership stabilises collective capacities (problem‑solving, learning, resilience) that exceed momentary interactions.

- Normative/legitimacy dimension: practices are embedded in rules, expectations, or obligations that shape who may lead and how influence is interpreted.

-

Operational definition (practice view):

- Leadership is the distributed set of routines, signals, rules, skills, and legitimacy‑bearing interactions that asymmetrically and repeatedly shape the probability of collective choices and coordinated actions toward shared or emergent outcomes.

-

How to test it empirically:

- Look for patterned asymmetries in influence, recurrence across episodes, coordination outcomes (vs. noise), and social or institutional mechanisms that confer credit, trust, or authority for those patterns.

This framing keeps the focus on what the group accomplishes through sustained practices, not on individual traits or isolated acts of influence.

Raelin, Joseph A., ed. Leadership-as-Practice: Theory and Application. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Śliwa, Martyna, and Peter Case. “Leadership-as-Practice: Appreciation, Critique, and Future Directions.” In The Routledge Critical Companion to Leadership Studies, edited by David Knights, Helena Liu, Owain Smolović-Jones, and Suze Wilson, 160–71. Routledge, 2024.

Collective and Relational Leadership

Aydın, Adnan Menderes. “Relational Leadership: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda.” MANAS Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi 15, no. 1 (2026): 126–45. https://doi.org/10.33206/mjss.1605660.

Collective leadership in practice often depends on collective intelligence, knowledge commons, and trans‑local networks that produce, curate, and circulate shared knowledges and practices across places.

- Collective intelligence: distributed sensing, cognition, and decision‑making across humans, nonhumans, and artefacts that combine diverse information and heuristics to bias action selection without a single commander.

- Knowledge commons: shared repositories, protocols, and stewardship norms that preserve, attribute, and validate practical knowledge; these commons create persistence, credit, and trust that make risk‑taking and coordinated following possible.

- Trans‑local networks: boundary spanners, interoperable infrastructures, and cross‑site relations that link local practices into wider patterns of influence, enabling diffusion, scale, and comparative learning.

Implications for leadership

- Leadership becomes an emergent, networked property: patterning of influence across nodes rather than sole individual authority.

- Infrastructure and metadata (provenance, credit, protocols) supply legitimacy and make following intelligible.

- Brokers, hubs, and boundary objects act as episodic leaders by translating, mobilising, or stabilising practices across contexts.

- Governance of the commons (rules, sanctions, licensing) shapes who can lead and how nonhuman knowledge sources are recognized.

Empirical signals to look for

- Shared, reusable repositories or artefacts with clear provenance and re‑use patterns.

- Recurring cross‑site coordination, templates, or protocols that bias outcomes.

- Visible attribution and credit systems that support trust in risky following.

- Network roles (hubs, brokers, periphery) correlated with directional influence and coordination outcomes.

- Inclusion of nonhuman sensors/actors or ecological processes as stable information sources or boundary objects.

This framing foregrounds how collective intelligence + commons + trans‑local ties produce the asymmetric, persistent, and coordinated influence.

Boelens, Rutgerd, Arturo Escobar, Karen Bakker, Lena Hommes, Erik Swyngedouw, Barbara Hogenboom, Edward H. Huijbens, et al. “Riverhood: Political Ecologies of Socionature Commoning and Translocal Struggles for Water Justice.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 50, no. 3 (2023): 1125–56. https://doi.org/10/hbcx99.

Comfort, Louise K., and Sandra L. Resodihardjo. “Leadership in Complex Adaptive Systems.” International Review of Public Administration 18, no. 1 (2013): 1–5. https://doi.org/10/hbcx98.

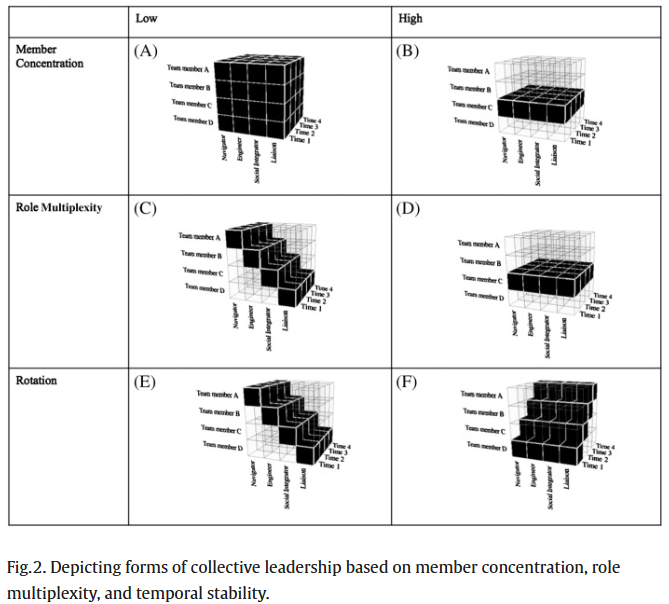

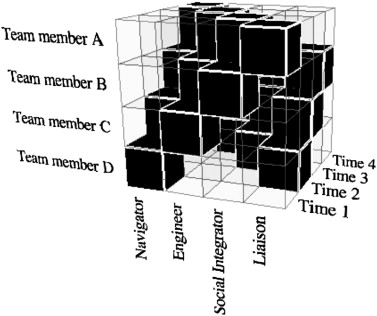

Contractor, Noshir S., Leslie A. DeChurch, Jay Carson, Dorothy R. Carter, and Brian Keegan. “The Topology of Collective Leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly 23, no. 6 (2012): 994–1011. https://doi.org/10/gf83kr.

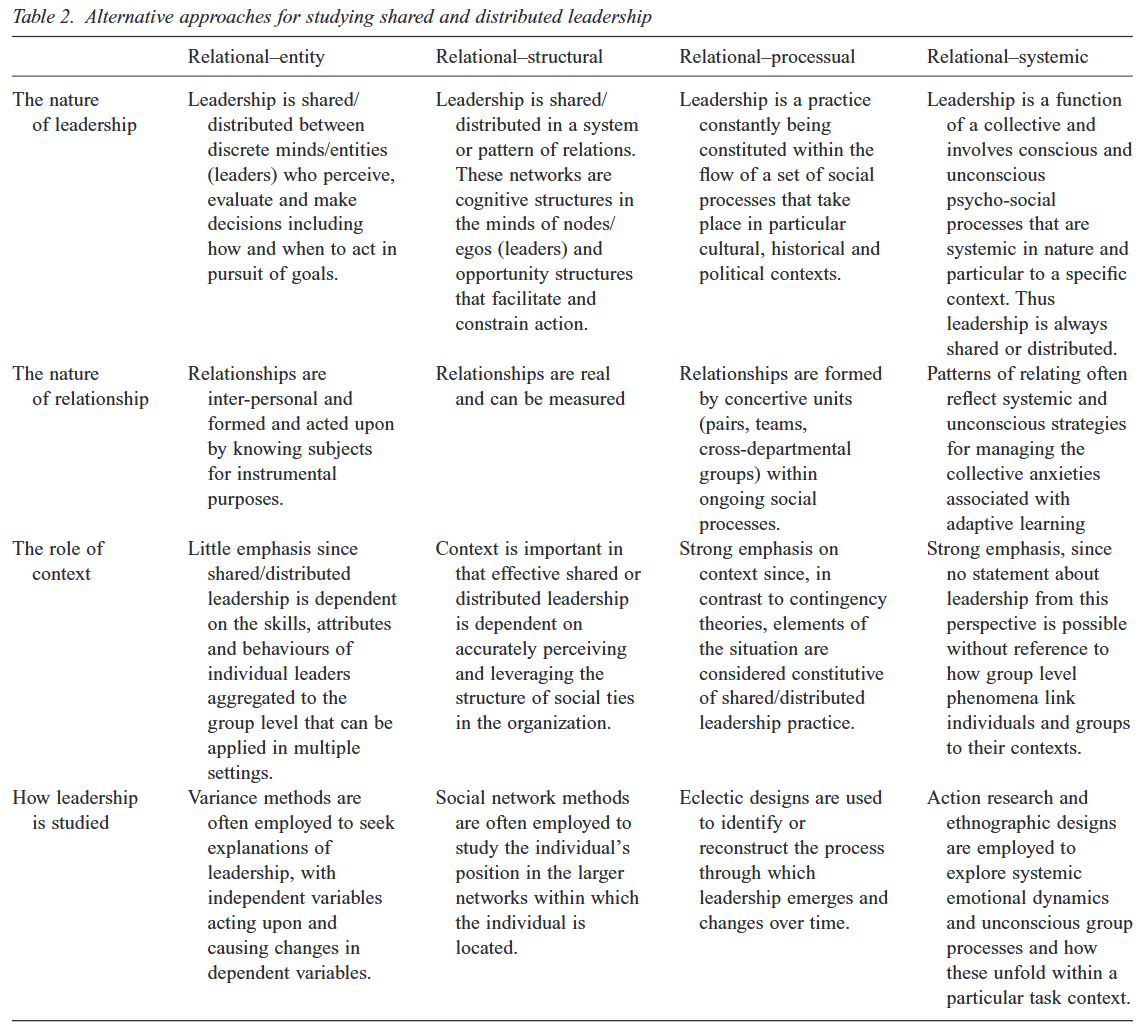

Fitzsimons, Declan, Kim Turnbull James, and David Denyer. “Alternative Approaches for Studying Shared and Distributed Leadership.” International Journal of Management Reviews 13, no. 3 (2011): 313–28. https://doi.org/10/bkvp69.

Friedrich, Tamara L., William B. Vessey, Matthew J. Schuelke, Gregory A. Ruark, and Michael D. Mumford. ‘A Framework for Understanding Collective Leadership: The Selective Utilization of Leader and Team Expertise Within Networks’. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, no. 6 (2009): 933–58. https://doi.org/10/fqxt9d.

Rosile, Grace Ann, David M Boje, and Carma M. Claw. ‘Ensemble Leadership Theory: Collectivist, Relational, and Heterarchical Roots from Indigenous Contexts’. Leadership 14, no. 3 (2018): 307–28. https://doi.org/10/gdgkt5.

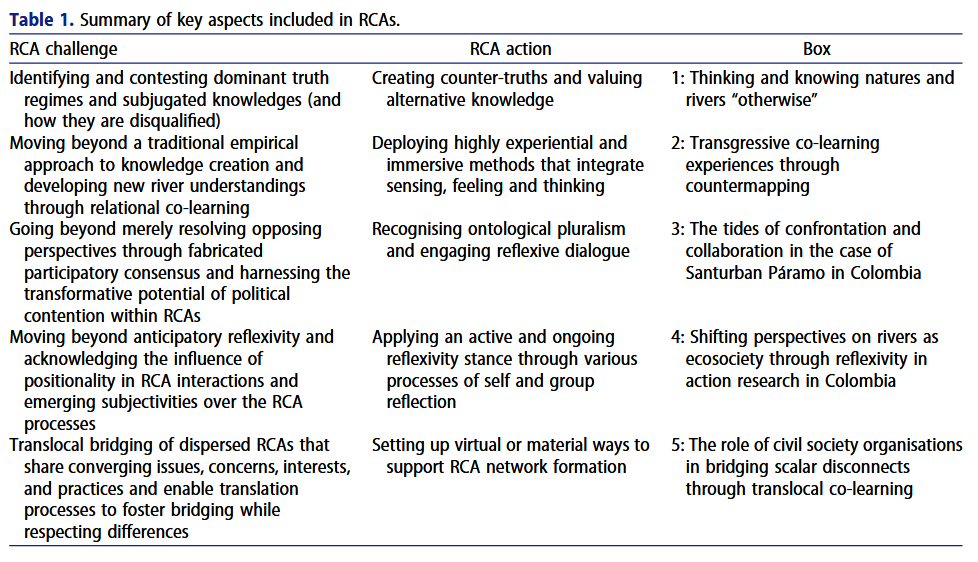

RCA: River Co-Learning Arenas

Souza, Daniele Tubino de, Lena Hommes, Arjen Wals, Jaime Hoogesteger, Rutgerd Boelens, Bibiana Duarte-Abadía, Juan Pablo Hidalgo-Bastidas, et al. “River Co-Learning Arenas: Principles and Practices for Transdisciplinary Knowledge Co-Creation and Multi-Scalar (Inter)Action.” Local Environment 30, no. 1 (2025): 58–80. https://doi.org/10/hbczbb.

Communicative Leadership

Barge, J. Kevin. “A Communicative Approach to Leadership.” In Origins and Traditions of Organizational Communication, edited by Anna M. Nicotera, 327–47. London: Routledge, 2019.

Related and Component Concepts

Needed because the term "leadership" is rarely used explicitly in more-than-human contexts. Closest you can get is “ecocentric leadership as stewardship”, engaging with leadership theory (collective leadership, complexity leadership) in application to ecocentric, relational, multispecies systems (but still human leadership).4

See

Nonhuman Expertise

Animals can learn, innovate, have some plasticity. this is interesting but does not have to be crucial. They are successful because they exist (have survived), as such they have done something well.

Dukas, Reuven. ‘Animal Expertise: Mechanisms, Ecology and Evolution’. Animal Behaviour 147 (2019): 199–210. https://doi.org/10/gfsp4n.

Prasher, Sanjay, Julian C. Evans, Megan J. Thompson, and Julie Morand-Ferron. ‘Characterizing Innovators: Ecological and Individual Predictors of Problem-Solving Performance’. PLOS ONE 14, no. 6 (2019): e0217464. https://doi.org/10/gmq6gn.

Rojas-Ferrer, Isabel, and Julie Morand-Ferron. ‘The Impact of Learning Opportunities on the Development of Learning and Decision-Making: An Experiment with Passerine Birds’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 375, no. 1803 (2020): 20190496. https://doi.org/10/ggzknt.

Snell-Rood, Emilie C., and Sean M. Ehlman. ‘Ecology and Evolution of Plasticity’. In Phenotypic Plasticity & Evolution, edited by David W. Pfennig, 139–60. CRC Press, 2021.

On expertise of leaders in ant teams:

Richardson, Thomas O., Andrea Coti, Nathalie Stroeymeyt, and Laurent Keller. ‘Leadership – Not Followership – Determines Performance in Ant Teams’. Communications Biology 4, no. 1 (2021): 1–9. https://doi.org/10/gmq6nq.

"This article provides evidence indicative of animals meeting each of the three definitions of expertise established in the scientific literature: expertise as a social construction, expertise as exceptional performance, and expertise as knowledge. In addition, cases of deliberate practice by non-human animals are offered. Acknowledging some animals as experts, regardless of consciousness, is warranted by the research findings and would prove useful in solving many issues remaining in the human expertise literature"

Helton, William S. ‘Animal Expertise, Conscious or Not’. Animal Cognition 8, no. 2 (2005): 67–74. https://doi.org/10/b88gx8.

Also in

Helton, William S., and Nicole D. Helton. ‘Expertise in Other Animals: Canines as an Example’. In The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, edited by K. Anders Ericsson, 2nd ed., 49–59. 2008. Reprint, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

For good definitions and the discussion of 'deliberate practice', with a mention of Helton and animals, see:

Suddendorft, Thomas, Melissa Brinums, and Kana Imuta. ‘Shaping One’s Future Self: The Development of Deliberate Practice’. In Seeing the Future: Theoretical Perspectives on Future-Oriented Mental Time Travel, edited by Kourken Michaelian, Stanley B. Klein, and Karl K. Szpunar, 343–66. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

This comprehensive book has example on expertise in Insects:

Córdoba-Aguilar, Alex, ed. Insect Behavior: From Mechanisms to Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

E.g., leadership in ant and termite teams.

-

Agency / animal agency / more‑than‑human agency

Working definition: capacity of humans and nonhumans to initiate actions that make a difference to ecological or governance outcomes (including learning, decision‑making, sociality, culture).

Relation to leadership: micro‑level basis of leadership: leadership can be treated as patterned, asymmetric Agency whose effects reliably shape collective behaviour or system trajectories. Animal‑agency and culture work show nonhumans influencing management outcomes in leadership‑like ways.5 -

Influence

Working definition: the effect an actor, relation, or process has on others’ behaviour, decisions, or on system‑level properties (e.g., movement routes, resource flows, resilience).

Relation to leadership: in relational/collective views, leadership ≈ patterned influence in interaction networks. Influence is the operational core of leadership; the question becomes “who/what influences what, when, and how?” across species and institutions.6 -

Stewardship / ecocentric leadership as stewardship

Working definition: ethos and practice of caring for and maintaining the integrity of ecological and multispecies systems over time, foregrounding humans‑as‑nature.

Relation to leadership: a normative mode of leadership: ecocentric stewardship treats human leadership as service to, and alignment with, living systems rather than control over them. Leadership becomes explicitly subservient to ecological flourishing.7 -

Governance

Working definition: the formal and informal rules, norms, and decision processes through which collective affairs (including conservation and coexistence) are coordinated.

Relation to leadership: Governance is the structural context within which leadership operates. A multispecies view asks how patterns of influence (leadership) are distributed within governance arrangements that include or recognize nonhuman participants.8 -

Commons / commoning / relational commons / more‑than‑human commons

Working definition: Commons as dynamic practices (“commoning”) that maintain shared socio‑ecological systems; relational commons and more‑than‑human commons explicitly include nonhumans and abiotic processes as part of the commons.

Relation to leadership: commoning is the arena in which multispecies leadership emerges: leadership becomes the emergent pattern of relations that “lead” toward or away from multispecies flourishing, rather than management of a human resource stock.9 -

Organizing / multispecies organizing

Working definition: ongoing coordination of activities, roles, and relations in “ecologies‑in‑place” that involve humans and other species.

Relation to leadership: organizing is the process, leadership is the pattern of influence within that process. Multispecies organizing foregrounds how nonhumans co‑shape what is possible, so that leadership becomes an emergent property of multispecies practices, not a human role.10 -

Care / more‑than‑human care / matters of care

Working definition: affective, practical, and ethical practices of attending and responding to needs of humans and nonhumans, often daily, reciprocal, and situated.

Relation to leadership: a particular style of leadership: influence exercised through attentive, situated, reciprocal Care. More‑than‑human care reorients leadership evaluation toward how well it sustains multispecies wellbeing, not only human goals.11 -

Coexistence / cohabitation

Working definition: dynamic states where humans and wildlife share landscapes through mutual adaptation; wildlife persists, risks are tolerable, and relations can include neutral, negative, and positive interactions.

Relation to leadership: coexistence is a system‑level outcome that leadership and governance try to sustain. Human and nonhuman actors “lead” systems toward particular coexistence archetypes via their behaviours, cultures, and institutional decisions.12 -

Trusteeship (non‑anthropocentric trusteeship)

Working definition: governance model in which some actors (trustees) hold authority and obligations to act on behalf of others’ interests, explicitly including nonhumans and future generations.

Relation to leadership: a specific leadership role: trustees exercise leadership for multispecies constituencies under strong normative constraints. Non‑anthropocentric trusteeship reframes human leadership as legally and ethically bound to follow multispecies justice claims.13 -

Sovereignty / multispecies or constitutional sovereignty

Working definition: claims about ultimate authority or self‑determination extended to nonhumans or ecosystems as political subjects (e.g., multispecies constitutional orders).

Relation to leadership: sovereignty sets outer limits and legitimacy conditions for leadership: human leadership must be reconfigured to respect or co‑ordinate with nonhuman and ecological sovereignty, rather than presuming exclusive human authority.14 -

Participation / more‑than‑human participation

Working definition: degrees and modes by which (human and nonhuman) actors are involved in decision‑making, from token consultation to co‑control.

Relation to leadership: participation schemes determine who gets to lead, and to what extent. More‑than‑human participation ladders explicitly ask how far nonhumans are allowed to exercise leadership‑like influence (up to co‑decision or co‑control).15 -

Representation (e.g., “Speakers for the Living,” Zoöp, rights‑of‑nature guardians)

Working definition: mechanisms where some humans formally speak or decide on behalf of nonhuman beings or ecosystems in legal, design, or institutional processes.

Relation to leadership: a mediated form of leadership: representatives hold derivative leadership authority; the quality of representation shapes whether nonhuman interests meaningfully lead outcomes or remain symbolic.16 -

Justice / multispecies justice

Working definition: normative frameworks for fair distribution, recognition, and participation across human and nonhuman beings; includes climate‑justice and coexistence framings that decentre humans.

Relation to leadership: provides the evaluative standard for leadership: leadership is legitimate when patterns of influence realize or approximate multispecies justice (e.g., addressing asymmetries, preventing multispecies suffering).17 -

Resilience (of coexistence)

Working definition: capacity of a human–wildlife system to stay in, or return to, a desired coexistence regime despite disturbances, typically defined by wildlife persistence, institutional legitimacy, and tolerable risk.

Relation to leadership: a performance criterion for leadership and governance at system scale: leadership patterns that stabilize desirable coexistence regimes and prevent shifts toward eradication or chronic conflict are “effective” in resilience terms.18 -

Culture / animal culture

Working definition: socially learned, shared behaviours within animal populations (e.g., migration routes, foraging techniques) that structure demography and responses to interventions.

Relation to leadership: often underpins informational leadership: culturally knowledgeable individuals and groups guide others, so their protection or loss can redirect system trajectories; leadership can be conceptualized around cultural influence nodes.19 -

Responsibility / political ecology of responsibility

Working definition: analytical and ethical focus on who has the power and obligation to act, given deep asymmetries between humans and nonhumans.

Relation to leadership: a critical lens on leadership: clarifies that, despite multispecies agency, humans typically hold disproportionate structural power and thus bear primary leadership responsibility for transforming systems toward justice.20 -

Kin‑centric / relational governance

Working definition: governance grounded in kinship, reciprocity, and relational ontologies where animals, spirits, and lands are relatives and co‑participants in decision‑making.

Relation to leadership: recasts leadership as kinship‑based relational influence: human leaders act as relatives and caretakers, closely following guidance, signals, and obligations emerging from more‑than‑human kin and places.21

Nonhuman Leadership

Animal Groups

Leadership occurs in nonhuman animal groups, e.g., elephants, wolves, dolphins, primates, birds, fish, insects. Leadership in these groups can involve decision-making about movement, foraging, social interactions, and conflict resolution. Nonhuman leadership often relies on social cues, communication signals, and established hierarchies or roles within the group.

Cf.:

- (Social) information transfer

- Management of extensive or ephemeral resources

- Dimensions of social organisation in animal groups

- Collaborative hunting (has also been applied as an approach to artificial agents. Does this mean that artificial agents can lead one another?22)

Followers are also important. For example, if fishes can choose whom to collaborate with, which might mean following the patterns the others have established, it means those others become leaders.23 To manage relevant information flows, that is: manage, compete for, delegate leaderships, fish can use referential gestures,24 octopi can punch fish,25 etc. (is this punching an example constituting animal husbandry the same as our example with powerful owls is an example of farming?).

"Leadership is ubiquitous within animal societies, occurring when one individual or subset of individuals, the leader(s), exert(s) a disproportional influence on the behaviors of others (followers)."

Smith, Jennifer E. 2017. “Non-Human Leadership.” In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science, edited by Todd K. Shackelford and Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford, 1–4. Cham: Springer.

The speed–accuracy trade-off paradigm illustrates how decision-making balances precision and urgency.26 For example, ant colonies, when conditions are favourable, wait for more approvals before selecting a new nest, prioritising accuracy. In contrast, under urgent circumstances, they decide with less verification to act quickly.27 This trade-off is most evident when the decision-maker possesses sufficient information but the pressure for speed leads to misinterpretation or premature action.

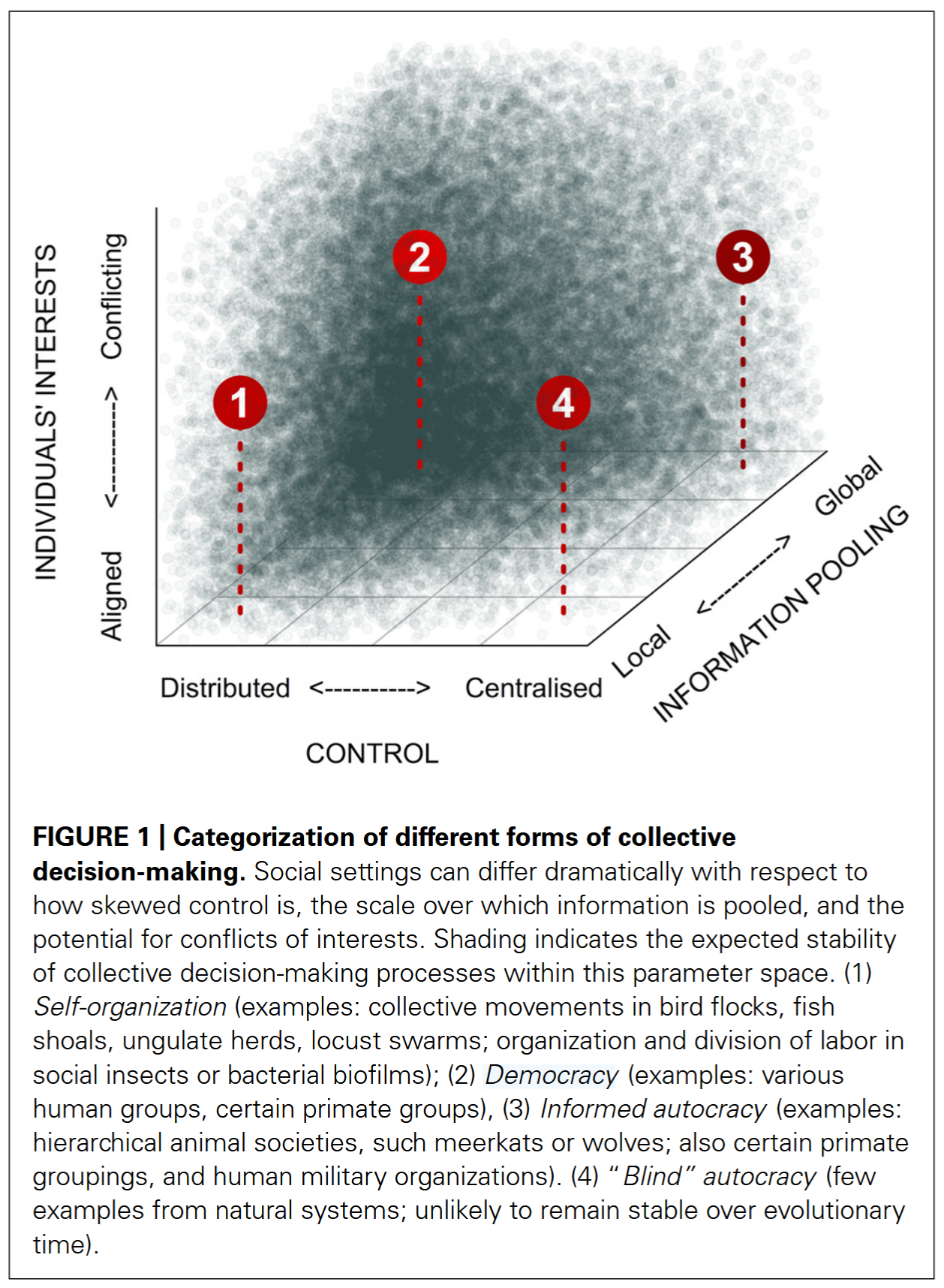

Microorganisms

Collective decision-making can range from centralized (autocratic/leader-driven) to distributed (democratic/egalitarian). In this context, "leadership" refers to situations where a single or a few individuals (or cells) have a disproportionate influence over group decisions, akin to a leader in animal or human societies. Decision-making systems distribute along axes such as the degree of control skew (from distributed to centralized) and the scale of information pooling (local vs. global).

Ross-Gillespie, Adin, and Rolf Kümmerli. 2014. “Collective Decision-Making in Microbes.” Frontiers in Microbiology 5: 00054. https://doi.org/10/gfzwnt.

References

Collinson, David L. “‘Only Connect!’: Exploring the Critical Dialectical Turn in Leadership Studies.” Organization Theory 1, no. 2 (2020): 2631787720913878. https://doi.org/10/ghx4vc.

Grint, Keith, and Owain Smolović Jones. Leadership: Limits and Possibilities. 2005. 2nd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2023.

Huopalainen, Astrid. ‘More-than-Human Leadership? Studying Leadership in Horse–Human Relationships’. In The Oxford Handbook of Animal Organization Studies, edited by Linda Tallberg and Lindsay Hamilton, 87–100. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Ives, Christopher D., Jenny Wilkinson, and Doug MacKie. “Ecological Leadership in a Planetary Emergency.” In The Handbook of Climate Change Leadership in Organisations, 129–54. London: Routledge, 2023.

Pietraszewski, David. 2020. “The Evolution of Leadership: Leadership and Followership as a Solution to the Problem of Creating and Executing Successful Coordination and Cooperation Enterprises.” The Leadership Quarterly, vol. 31 (2): 101299. https://doi.org/10/gf39dn.

Smith, Jennifer E. ‘Non-Human Leadership’. In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science, edited by Todd K. Shackelford and Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford, 1–4. Cham: Springer, 2017.

Somoza-Norton1, Andrea, Claudia I. Rivera Cárdenas, Lisa Pabigian, and Megan Drap. “Biomimetic Leadership: Core Beliefs for Sustainable Organizations.” Journal of Ecohumanism 2, no. 1 (2023): 77–91. https://doi.org/10/hbgfrn.

Winchester, Nik. “Leadership and Posthuman Ethics.” In The Routledge Critical Companion to Leadership Studies, edited by David Knights, Helena Liu, Owain Smolović-Jones, and Suze Wilson, 52–63. New York: Routledge, 2024.

y use of LLMs. If you use them, state how you used them and label AI-generated content on Miro. Do not present AI output as your own work.

- Include at least two pe

Footnotes

De Dreu, Carsten K. W., and Zegni Triki. “Intergroup Conflict: Origins, Dynamics and Consequences across Taxa.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 377, no. 1851 (2022): 20210134. https://doi.org/10/gqxnmv.˄

Whiten, Andrew, Dora Biro, Nicolas Bredeche, Ellen C. Garland, and Simon Kirby. “The Emergence of Collective Knowledge and Cumulative Culture in Animals, Humans and Machines.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 377, no. 1843 (2021): 20200306. https://doi.org/10/gnz8t2.˄

Fairhurst, Gail T., and Mary Uhl-Bien. “Organizational Discourse Analysis (ODA): Examining Leadership as a Relational Process.” The Leadership Quarterly 23, no. 6 (2012): 1043–62. https://doi.org/10/gfzswn.˄

Tushman, Michael L., and David A. Nadler. “Information Processing as an Integrating Concept in Organizational Design.” The Academy of Management Review 3, no. 3 (1978): 613–24. https://doi.org/10/frrhd7.˄

Galbraith, Jay R. Designing Complex Organizations. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1973.˄

Ritter, Luea, and Anaïs Sägesser. “Toward an Ecocentric Leadership as Stewardship Framework: Insights from Fostering Transformative Partnerships and Collective Practice.” Earth Stewardship 2, no. 5 (2025): e70027. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpx.˄

Edelblutte, Émilie, Roopa Krithivasan, and Matthew Nassif Hayek. “Animal Agency in Wildlife Conservation and Management.” Conservation Biology 37, no. 1 (2023): e13853. https://doi.org/10/gqkjfs. Steinhardt, Margarita, Susanne Pratt, and Daniel Ramp. “Re-Thinking Felid–Human Entanglements through the Lenses of Compassionate Conservation and Multispecies Studies.” Animals 12, no. 21 (2022): 2996. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpv. Bhattacharyya, Jonaki, and Scott Slocombe. “Animal Agency: Wildlife Management from a Kincentric Perspective.” Ecosphere 8, no. 10 (2017): e01978. https://doi.org/10/gch9v4.˄

Edelblutte, Émilie, Roopa Krithivasan, and Matthew Nassif Hayek. “Animal Agency in Wildlife Conservation and Management.” Conservation Biology 37, no. 1 (2023): e13853. https://doi.org/10/gqkjfs. Brakes, Philippa, Emma Carroll, Sasha Dall, Sally Keith, Peter McGregor, Sarah Mesnick, Michael Noad, et al. “A Deepening Understanding of Animal Culture Suggests Lessons for Conservation.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288, no. 1949 (2021): 20202718. https://doi.org/10/gjr2tm. Marchini, Silvio, Katia M. P. M. B. Ferraz, Vania Foster, Thiago Reginato, Aline Kotz, Yara Barros, Alexandra Zimmermann, and David W. Macdonald. “Planning for Human-Wildlife Coexistence: Conceptual Framework, Workshop Process, and a Model for Transdisciplinary Collaboration.” Frontiers in Conservation Science 2 (2021): 752953. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpw.˄

Ritter, Luea, and Anaïs Sägesser. “Toward an Ecocentric Leadership as Stewardship Framework: Insights from Fostering Transformative Partnerships and Collective Practice.” Earth Stewardship 2, no. 5 (2025): e70027. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpx. S. Riley, Sophie. “Listening to Nature’s Voice: Invasive Species, Earth Jurisprudence and Compassionate Conservation.” Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law 22, no. 1 (2019): 117–36. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpz.˄

Moon, Katie, Dru Marsh, Benjamin Cooke, and Richard Kingsford. “Relational Commons: An Ontological and Governance Framework beyond Protected Areas and the Boundaries of Conservation.” Conservation Letters 18, no. 5 (2025): e13137. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp4. Paul, Andrew, Robin Roth, and Saw Sha Bwe Moo. “Relational Ontology and More-than-Human Agency in Indigenous Karen Conservation Practice.” Pacific Conservation Biology 27, no. 4 (2021): 376–90. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp5. Marchini, Silvio, Katia M. P. M. B. Ferraz, Vania Foster, Thiago Reginato, Aline Kotz, Yara Barros, Alexandra Zimmermann, and David W. Macdonald. “Planning for Human-Wildlife Coexistence: Conceptual Framework, Workshop Process, and a Model for Transdisciplinary Collaboration.” Frontiers in Conservation Science 2 (2021): 752953. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpw. Carter, Neil H., and John D. C. Linnell. “Building a Resilient Coexistence with Wildlife in a More Crowded World.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Nexus 2, no. 3 (2023): pgad030. https://doi.org/10/j2tx.˄

Bresnihan, Patrick. “The More-than-Human Commons: From Commons to Commoning.” In Space, Power and the Commons, edited by Samuel Kirwan, Leila Dawney, and Julian Brigstocke, 93–112. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016. Moon, Katie, Dru Marsh, Benjamin Cooke, and Richard Kingsford. “Relational Commons: An Ontological and Governance Framework beyond Protected Areas and the Boundaries of Conservation.” Conservation Letters 18, no. 5 (2025): e13137. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp4. Ressiore C., Adriana, David Ludwig, and Charbel El-Hani. “The Conceptual Potential of ‘More-than-Human Care’: A Reflection with an Artisanal Fishing Village in Brazil.” Geo: Geography and Environment 11, no. 2 (2024): e00159. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp6.˄

Ehrnström-Fuentes, Maria, Steffen Böhm, Sophia Hagolani-Albov, and Linda Annala Tesfaye. “Multispecies Organizing in the Web of Life: Ethico-Political Dynamics of Matters of Care in Ecologies-in-Place.” Business Ethics Quarterly, 2025, 1–30. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp7.˄

Maria Ehrnström‑Fuentes et al., “Multispecies Organizing in the Web of Life: Ethico‑Political Dynamics of Matters of Care in Ecologies‑in‑Place,” Business Ethics Quarterly (2025); Meg Parsons, “Governing with Care, Reciprocity, and Relationality: Recognising the Connectivity of Human and More‑Than‑Human Wellbeing and the Process of Decolonisation,” Dialogues in Human Geography (2023); Ressiore C., Adriana, David Ludwig, and Charbel El-Hani. “The Conceptual Potential of ‘More-than-Human Care’: A Reflection with an Artisanal Fishing Village in Brazil.” Geo: Geography and Environment 11, no. 2 (2024): e00159. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp6.˄

Pooley, Simon, Saloni Bhatia, and Anirudhkumar Vasava. “Rethinking the Study of Human–Wildlife Coexistence.” Conservation Biology 35, no. 3 (2021): 784–93. https://doi.org/10/gkr7bg. Marchini, Silvio, Katia M. P. M. B. Ferraz, Vania Foster, Thiago Reginato, Aline Kotz, Yara Barros, Alexandra Zimmermann, and David W. Macdonald. “Planning for Human-Wildlife Coexistence: Conceptual Framework, Workshop Process, and a Model for Transdisciplinary Collaboration.” Frontiers in Conservation Science 2 (2021): 752953. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpw. Carter, Neil H., and John D. C. Linnell. “Building a Resilient Coexistence with Wildlife in a More Crowded World.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Nexus 2, no. 3 (2023): pgad030. https://doi.org/10/j2tx. Jolly, Helina, and Amanda Stronza. “Insights on Human−wildlife Coexistence from Social Science and Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge.” Conservation Biology 39, no. 2 (2025): e14460. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp8.˄

Santiago-Ávila, Francisco J., and Adrian Treves. “Toward Multispecies Justice in Human–Wildlife Coexistence: Reply to Clark et. Al.” Conservation Biology 35, no. 4 (2021): 1337–40. https://doi.org/10/hbcvqc. Riley, Sophie. “Listening to Nature’s Voice: Invasive Species, Earth Jurisprudence and Compassionate Conservation.” Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law 22, no. 1 (2019): 117–36. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpz.˄

Santiago-Ávila, Francisco J., and Adrian Treves. “Toward Multispecies Justice in Human–Wildlife Coexistence: Reply to Clark et. Al.” Conservation Biology 35, no. 4 (2021): 1337–40. https://doi.org/10/hbcvqc. Tschakert, Petra, David Schlosberg, Danielle Celermajer, Lauren Rickards, Christine Winter, Mathias Thaler, Makere Stewart-Harawira, and Blanche Verlie. “Multispecies Justice: Climate-Just Futures with, for and beyond Humans.” WIREs Climate Change 12, no. 2 (2021): e699. https://doi.org/10/ghq9vw.˄

Roudavski, Stanislav. “The Ladder of More-than-Human Participation: A Framework for Inclusive Design.” Cultural Science 14, no. 1 (2024): 110–19. https://doi.org/10/g8nn27. Light, Ann. “More-than-Human Participatory Approaches for Design: Method and Function in Making Relations.” Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2024: Exploratory Papers and Workshops (New York), PDC ’24, vol. 2 (2024): 1–6. https://doi.org/10/g8p392.˄

Haldrup, Michael, Kristine Samson, and Thomas Laurien. “Designing for Multispecies Commons: Ecologies and Collaborations in Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022, edited by Vasilis Vlachokyriakos, Joyce Yee, Christopher Frauenberger, Melisa Duque Hurtado, Nicolai Hansen, Angelika Strohmayer, Izak Van Zyl, et al., 2:14–19. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2022. https://doi.org/10/gq6sfx. Roudavski, Stanislav. “Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design.” In Proceedings of Design Research Society (DRS) 2020 International Conference: Synergy, edited by Stella Boess, Ming Cheung, and Rebecca Cain, 731–50. London: Design Research Society, 2020. https://doi.org/10/ghj48x. Houart, Carlota, Jaime Hoogesteger, and Rutgerd Boelens. “Power and Politics across Species Boundaries: Towards Multispecies Justice in Riverine Hydrosocial Territories.” Environmental Politics 34, no. 1 (2025): 49–69. https://doi.org/10/hbcvqs. Light, Ann. “More-than-Human Participatory Approaches for Design: Method and Function in Making Relations.” Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2024: Exploratory Papers and Workshops (New York), PDC ’24, vol. 2 (2024): 1–6. https://doi.org/10/g8p392.˄

Tschakert, Petra, David Schlosberg, Danielle Celermajer, Lauren Rickards, Christine Winter, Mathias Thaler, Makere Stewart-Harawira, and Blanche Verlie. “Multispecies Justice: Climate-Just Futures with, for and beyond Humans.” WIREs Climate Change 12, no. 2 (2021): e699. https://doi.org/10/ghq9vw. Steinhardt, Margarita, Susanne Pratt, and Daniel Ramp. “Re-Thinking Felid–Human Entanglements through the Lenses of Compassionate Conservation and Multispecies Studies.” Animals 12, no. 21 (2022): 2996. https://doi.org/10/hbcvpv. Carter, Neil H., and John D. C. Linnell. “Building a Resilient Coexistence with Wildlife in a More Crowded World.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Nexus 2, no. 3 (2023): pgad030. https://doi.org/10/j2tx. Fieuw, Walter, Marcus Foth, and Glenda Amayo Caldwell. “Towards a More-than-Human Approach to Smart and Sustainable Urban Development: Designing for Multispecies Justice.” Sustainability 14, no. 2 (2022): 948. https://doi.org/10/gn7k62.˄

Carter, Neil H., and John D. C. Linnell. “Building a Resilient Coexistence with Wildlife in a More Crowded World.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Nexus 2, no. 3 (2023): pgad030. https://doi.org/10/j2tx.˄

Brakes, Philippa, Emma Carroll, Sasha Dall, Sally Keith, Peter McGregor, Sarah Mesnick, Michael Noad, et al. “A Deepening Understanding of Animal Culture Suggests Lessons for Conservation.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288, no. 1949 (2021): 20202718. https://doi.org/10/gjr2tm. Pooley, Simon, Saloni Bhatia, and Anirudhkumar Vasava. “Rethinking the Study of Human–Wildlife Coexistence.” Conservation Biology 35, no. 3 (2021): 784–93. https://doi.org/10/gkr7bg.˄

Komi, Sanna, and Anja Nygren. “Bad Wolves? Political Ecology of Responsibility and More-than-Human Perspectives in Human–Wildlife Interactions.” Society & Natural Resources 36, no. 10 (2023): 1238–56. https://doi.org/10/hbcvqv. Pooley, Simon. “Coexistence for Whom?” Frontiers in Conservation Science 2 (2021): 726991. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.726991.˄

Bhattacharyya, Jonaki, and Scott Slocombe. “Animal Agency: Wildlife Management from a Kincentric Perspective.” Ecosphere 8, no. 10 (2017): e01978. https://doi.org/10/gch9v4. Paul, Andrew, Robin Roth, and Saw Sha Bwe Moo. “Relational Ontology and More-than-Human Agency in Indigenous Karen Conservation Practice.” Pacific Conservation Biology 27, no. 4 (2021): 376–90. https://doi.org/10/hbcvp5. Parsons, Meg. “Governing with Care, Reciprocity, and Relationality: Recognising the Connectivity of Human and More-than-Human Wellbeing and the Process of Decolonisation.” Dialogues in Human Geography 13, no. 2 (2023): 288–92. https://doi.org/10/hbcvqx.˄

Tsutsui, Kazushi, Ryoya Tanaka, Kazuya Takeda, and Keisuke Fujii. 2024. “Collaborative Hunting in Artificial Agents with Deep Reinforcement Learning.” eLife 13: e85694. https://doi.org/10/hbfdvp.˄

Vail, Alexander L., Andrea Manica, and Redouan Bshary. 2014. “Fish Choose Appropriately When and with Whom to Collaborate.” Current Biology 24 (17): R791–93. https://doi.org/10/hbff4z.˄

Vail, Alexander L., Andrea Manica, and Redouan Bshary. 2013. “Referential Gestures in Fish Collaborative Hunting.” Nature Communications 4 (1): 1765. https://doi.org/10/f4tx5d.˄

Sampaio, Eduardo, Martim Costa Seco, Rui Rosa, and Simon Gingins. 2021. “Octopuses Punch Fishes during Collaborative Interspecific Hunting Events.” Ecology 102 (3): 1–4. https://doi.org/10/gv45z8.˄

Busemeyer, Jerome R., and James T. Townsend. 1993. “Decision Field Theory: A Dynamic-Cognitive Approach to Decision Making in an Uncertain Environment.” Psychological Review 100 (3): 432–59. https://doi.org/10/ftnp84.˄

Franks, Nigel R., Anna Dornhaus, Jon P. Fitzsimmons, and Martin Stevens. 2003. “Speed versus Accuracy in Collective Decision Making.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 270 (1532): 2457–63. https://doi.org/10/fqxzpc.˄

Backlinks