Design

Definitions

The term design refers to collective processes of constructing conditions that can support life in response to novel circumstances.

Goals

- Reverse the past, ongoing and future human-induced damage

- Improve wellbeing

- Respect for 'nature' and designing 'with' 'nature' are not enough, the existing and locked-in damages are too great

- Design for nonhuman stakeholders, explicitly

Challenges

- It is not possible to make everyone 'better off'

- It is not always good to have more biomass or more biodiversity

- Environments without humans have plenty of suffering

- It is not clear what success looks like

Commercial design is really a way to pray on powerful evolved mechanisms inherent to human beings such as patterns of feeding, information seeking, socialising, having sex, etc. Successful products claim to predict new needs, such as social media or smartphones, but actually depend on human inability to control urges. This is mining of urges, a form of extractivism and enslavement.

Synonyms

- Ecocentric Design

- more-than-human design

- animal-computer interaction

- self-design, design in nature, ecosystem engineers,1 ecosystem engineers can be invasive, niche construction

- design without designers, vernacular design, etc.

- Interspecies Design, design conducted with other species

- ecological design Ecological Engineering

- Ecological Engineering

- Rewilding, Rewilding

- nature-positive, net-positive design

- Animal Aided Design

- nature-centred design

- green, sustainable and transition design, green skyscrapers

- cradle to cradle

- Biomimicry

- regenerative design 3

- permaculture

- living machines 4

- urban villages

- resource-autonomous buildings

- deep design 2

- reuse, repair, retrofitting

Mineral Construction

Uniquely in the Solar system the Earth has some 4000 minerals. Other planets that have advanced further along the line of planetary 'evolution' many have up to 1000. The rest are the results of the living process on Earth.

Limitations

Earth is unsubstitutable, it cannot be replicated in a laboratory and always escapes the hubris of those who would remake and master it.

Neyrat, Frédéric. The Unconstructable Earth An Ecology of Separation. Translated by Drew S. Bruk. New York: Fordham University Press, 2019.

Current Impact and Opportunities for Contribution

The common understanding of the role of design severely diminishes its actual impact in the eye of the human stakeholders.

The consequence is commodification of design.

Another form of a negative impact is 'design blindness'. This is also an serious, substantial and readily available opportunity for contribution.

Birkeland, Janis. “Design Blindness in Sustainable Development: From Closed to Open Systems Design Thinking.” Journal of Urban Design 17, no. 2 (2012): 163–87. https://doi.org/10/gqg4v8.

"Over time, regulations evolved from end-of-pipe environmental controls, to middle-of-pipe cleaner production, to front-of-pipe eco-efficiency, and finally to closed-pipe systems design." p. 167

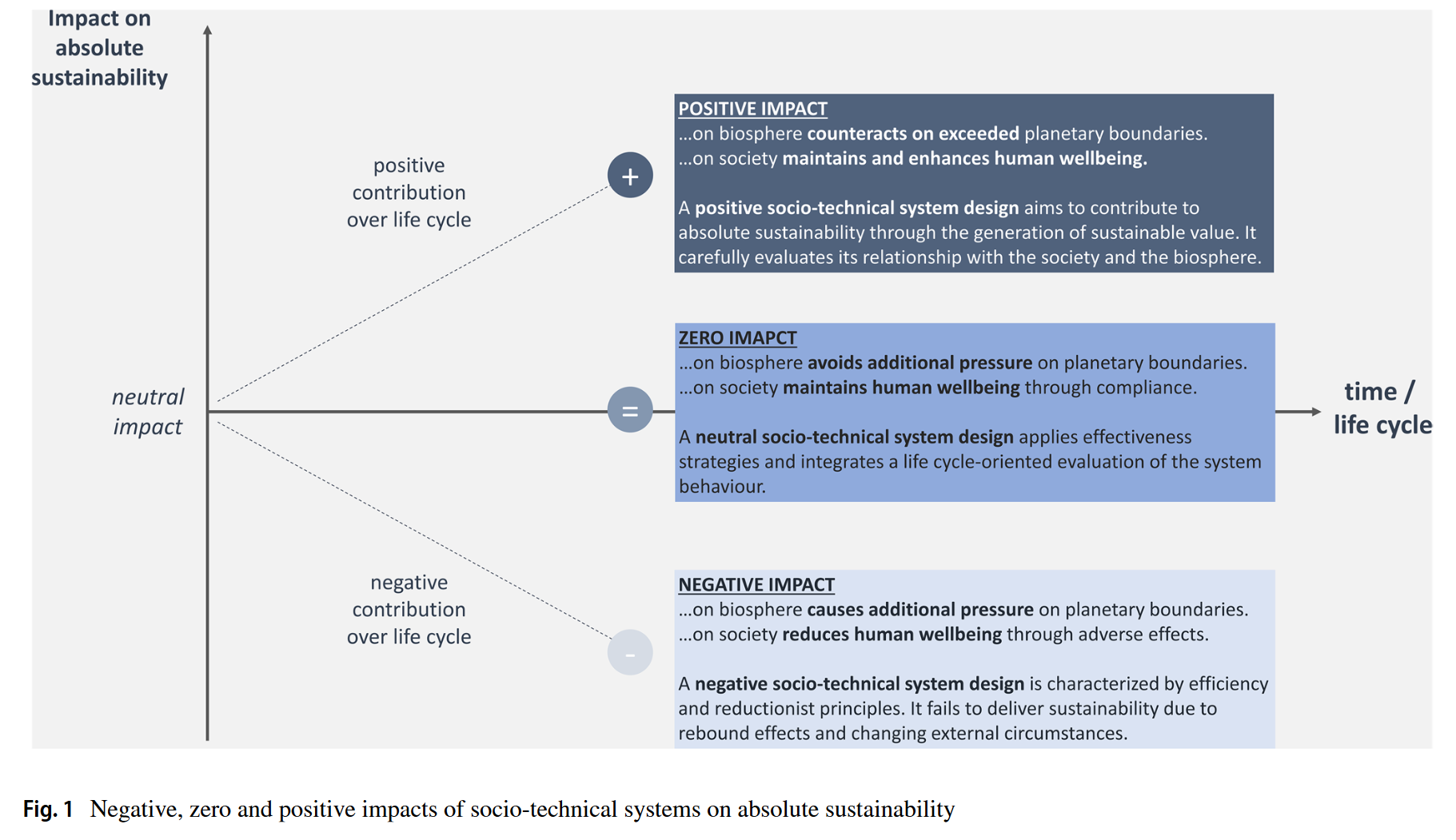

Making a positive contribution to compensate for the damage is another opportunity.

Gebler, Malte, Max Juraschek, Sebastian Thiede, Felipe Cerdas, and Christoph Herrmann. “Defining the ‘Positive Impact’ of Socio-Technical Systems for Absolute Sustainability: A Literature Review Based on the Identification of System Design Principles and Management Functions.” Sustainability Science, 2022. https://doi.org/10/gqg4wm.

What is Design?

What are the core, irreducible properties of 'design'?

- objectives

- directionality, which we can also interpret as the creation of novelty, innovation

- local resistance to entropy, in this way design is synonymous with all life

- constraints

- path dependency, for all practical considerations, there is history, it defines what is possible

- resource finality (space, reach, time, energy, materials, information...)

- contingency and imperfection of all possible solutions

- evolution (of all types), the conditions of constraint change, however fast or slow (one of the things that makes perfection in design impossible and attempts at it problematic)

It is hard to define what design 'is'. It is not a phenomenon out there but rather a pragmatic concept with some usefulness. Thus, it is easier to:

- discuss what it means to certain stakeholders in certain settings

- access the benefits of each interpretation, against transparent criteria (better justice, more thriving, more freedom, more life, more innovation, etc.)

Do We Need to Rethink Designing?

Another important question to answer is whether it is reasonable or necessary to broaden the conventional understanding of design in the way suggested above. Our answer here is that conventional design-practices are clearly inadequate. It is also clear that these practices are driven by the current definitions. A modest update to the current definitions might be possible in principle. However, it is not clear where the boundary of this modesty should lie. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the full spectrum of possible updates before deciding what is adequate to the challenges in question.

Designing by Human Individuals or Opportunistic Groups

A typical presumption is that design is done by human individuals or human groups that are specifically assembled to address a particular topic, for example architecture, or a specific project, for example a bridge.

Such human design - professionally - is a responsibility for making plans for some future. As such, it is always biased, towards the current moment, towards the client, towards the available knowledge, or the current style/fashion, or towards the financial opportunities.

It is biased towards humans and their particular ways of being: human spatial scales, human time scales, human narratives, etc. Design is subdivided by discipline and by project. These are defined by the contingencies of careers, regulations, financial or electoral cycles, etc.

A large range of issues lifestyles and concerns are not accessible to this form of design.

Designing by Human Collectives

Notions such as participatory or situated design recognise that design projects always involve heterogeneous stakeholders many of whom are not professional designers. These interpretations recognise contingent, emergent, and relational nature of design decisions and design outcomes.

The point here is that human designing seen as provision of platonic blueprints is a form of delusion that depends on the unwitting or wilful exclusion of externalities.

In reality, designing is always collective, always contingent, always hazy. Rather than goals, it has tendencies. Any individual goal is always partial and in relationship plus tension with other goals.

Continuing from here, all goals are illusions. They are temporally, spatially, and cognitively local interpretations of the process by agents with limited capabilities (time, information processing resources, etc.).

Designing by More-than-Human Collectives

From first principles, one could attempt to define design as characteristic of all life. From this standpoint, designing is a biotic phenomenon.

If designing is a collective endeavour and the collective includes nonhuman lifeforms, the consequences are more complicated and open-ended. In a more-than-human collective, there are multiple umwelten, multiple information-processing modes, multiple needs and goals, all evolving.

Here, design is always a composite, like cubism, composed from patchworks of perspectives but more than cubism because the perspectives can be substantially different as is evident in the research into sensory ecologies and behavioural ecologies of nonhuman begins.

In this interpretation, there is no privileged view on design or its components such as decisions, criteria, etc. All stakeholders have views and all views are partial. All decisions are biased and the decisions that become implemented are an expression of stakeholder imposition, that can be more violent or more negotiated.

Designing by Nonhuman Individuals or Close Groups

In our interpretation the discussion of individuals or close groups is not very meaningful given the relational and processual nature of all beings. However interpretations that focus on individuals are very common. For example, such interpretations can focus on the survival and 'design' by genes, individual organisms, kinship-based groups such as families, and so on.

Designing in/by Non-Living Systems

Directionality and dynamics of non-livings systems are inseparable from life. Thus, it is possible to say that non-living world self-designs too.

The debate on the relevant issues is very open but cf. the computational nature of the universe, the primacy of information, panpsychism, universal sentience, etc.

Examples of self-design in the nonliving world include geological formations, the emergence of atmospheres on Planets or stars, weather dynamics, the emergence of tectonic plate dynamics, the convection mechanisms in the magma, and, therefore, the magnetic field on the Earth (and the current absence of this on the now-cold Mars), the dynamics of water flows in the oceans in the Earth with its contemporary 10,000-year cycle, and many other phenomena.

References

These are on topic but appear here for the context, without critique or endorsement.

Wakkary, Ron. Things We Could Design: For More Than Human-Centered Worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

Pawlyn, Michael, and Sarah Ichioka. Flourish: Design Paradigms for Our Planetary Emergency. Axminster: Triarchy, 2022.

Deep Design Lab on Design

Holland, Alexander, and Stanislav Roudavski. ‘Participatory Design for Multispecies Cohabitation: By Trees, for Birds, with Humans’. In Designing More-than-Human Smart Cities: Beyond Sustainability, Towards Cohabitation, edited by Sara Heitlinger, Marcus Foth, and Rachel Clarke, 93–128. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10/m7z3.

Parker, Dan, Stanislav Roudavski, Bronwyn Isaac, and Nick Bradsworth. ‘Toward Interspecies Art and Design: Prosthetic Habitat-Structures in Human-Owl Cultures’. Leonardo 55, no. 4 (2022): 351–56. https://doi.org/10/hwkm.

Parker, Dan, Kylie Soanes, and Stanislav Roudavski. ‘Interspecies Cultures and Future Design’. Transpositiones 1, no. 1 (2022): 183–236. https://doi.org/10/gpvsfs.

Roudavski, Stanislav. ‘Interspecies Design’. In Cambridge Companion to Literature and the Anthropocene, edited by John Parham, 147–62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Roudavski, Stanislav. ‘Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design’. In Proceedings of Design Research Society (DRS) 2020 International Conference: Synergy, edited by Stella Boess, Ming Cheung, and Rebecca Cain, 731–50. London: Design Research Society, 2020. https://doi.org/10/ghj48x.

Subnotes

Footnotes

Cuddington, Kim, ed. Ecosystem Engineers: Plants to Protists. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 2007.˄

Mang, Pamela, and Ben Haggard. Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability. Hoboken: Wiley, 2016.˄

Todd, Nancy Jack, and John Todd. From Eco-Cities to Living Machines: Principles of Ecological Design. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 1994.˄

Wann, David. Deep Design: Pathways to a Livable Future. Washington: Island Press, 1995.˄

Backlinks