Approaches to Designing

This note is about designing as a method for exploration, imagination, generation of new knowledge, new relationships, new futures.

Cf.

- Design, see the children notes of this concept note, for example probes.examples.design.speculative (Private), Participatory Design.

- Speculation, on the concept and uses of speculation across disciplines.

- critical approaches to multiple disciplines, e.g., critical GIS, Critical Animal Studies, critical data studies, etc.

Table of Contents

Designing

For the purposes of this note, a brief clarification about design:

- Design is not about constructing arbitrary desires to sell products by making them visually or symbolically appealing.

- It is a way to foster innovation and imagine consequences of decisions that aim to address systemic issues such as health, wellbeing, and justice.

Principles

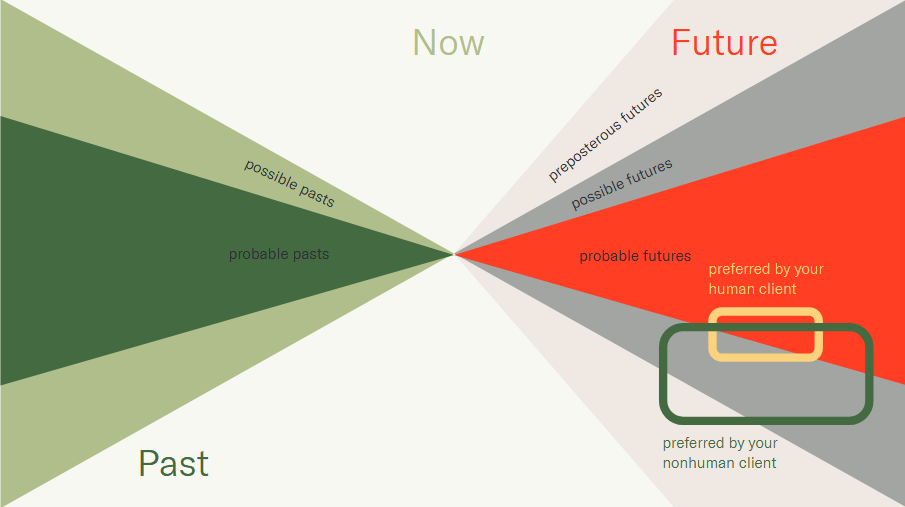

Orientation Towards the Future

- Focus on envisioning possible futures rather than solving current problems.

- Encourage imaginative and forward-thinking scenarios.

On ethics, politics, and aesthetics as a narrative about designing for more-than-human cultures, see:

Roudavski, Stanislav. “Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design.” In Proceedings of Design Research Society (DRS) 2020 International Conference: Synergy, edited by Stella Boess, Ming Cheung, and Rebecca Cain, 731–50. London: Design Research Society, 2020. https://doi.org/10/ghj48x.

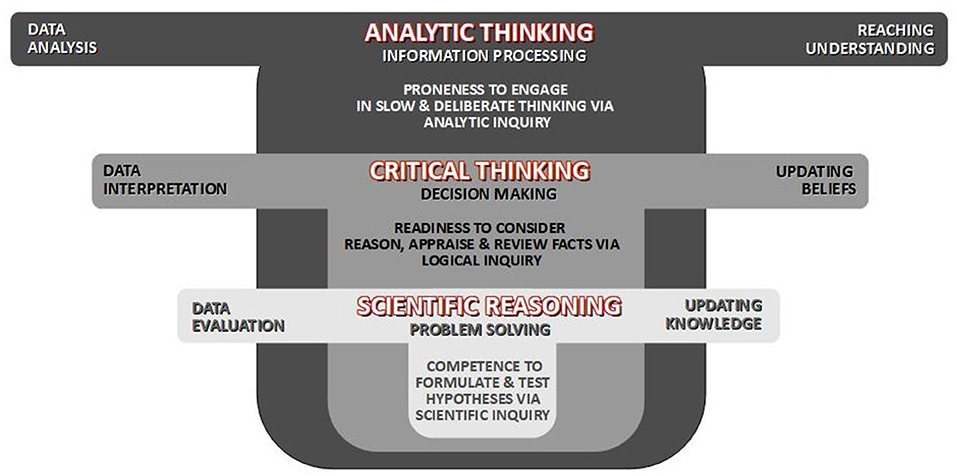

Analytical Thinking, Critical Thinking, and Scientific Reasoning

'Critical thinking' is readiness to consider, reason, appraise, review, and interpret facts to update existing beliefs.

Encompassing to 'critical thinking' is 'analytical thinking' or slow and deliberate processing of information to mitigate biases and reach an objective understanding of facts.

Underlying critical thinking is 'scientific reasoning' or the commitment to use principles and measurement for the evaluation of facts.

Gjoneska, Biljana. “Conspiratorial Beliefs and Cognitive Styles: An Integrated Look on Analytic Thinking, Critical Thinking, and Scientific Reasoning in Relation to (Dis)Trust in Conspiracy Theories.” Frontiers in Psychology 12 (2021): 736838. https://doi.org/10/gqbqq2.

Failure in any of the integrated domains can lead to an increase in conspiratorial beliefs as a signal of 'crippled epistemology'.

Sunstein, Cass R., and Adrian Vermeule. “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures.” Journal of Political Philosophy 17, no. 2 (2009): 202–27. https://doi.org/10/bdd3hg.

- Challenge existing norms and assumptions.

- Use design to provoke thought and discussion about societal issues.

- Aim to reduce uncertainty through measurement in all situations.

- Use best available and verifiable evidence to inform decisions.

Readiness to Engage with Pluralism

Dominant approaches to the construction of knowledge and to practice often exclude worldviews of less powerful stakeholders such as political opponents, humans with different education, knowledge from other disciplines, or the expertise of non-human entities.

- Include diverse stakeholders and expert, consider differing worldviews, and knowledge systems.

- Adopt integrative, comparative or alternative approaches.

Roudavski, Stanislav, ed. “Design for All Life.” Special issue. Architect Victoria 3 (2022): 32–75. https://doi.org/10/gr3wfb.

For the discussion on the multiple worlds in relationship to design, see:

Escobar, Arturo. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Narrative Exposition of Stakeholder Experiences

- Create compelling stories to express complex and unobvious relationships and experiences.

- Use narratives to make abstract concepts tangible and relatable.

Ethical Considerations

- Consider ethical implications of future-oriented decisions.

- Consider the impact on various stakeholders, including non-human entities.

Methods

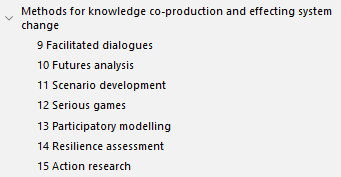

Methods are ways to operationalize the principles of designing. This section includes some methods that can be used to explore speculative and future-oriented design.

In this handbook, they fall under the rubric of methods for co-production and effecting system change.

Biggs, Reinette, Rika Preiser, Alta De Vos, Maja Schlüter, Kristine Maciejewski, and Hayley Clements. The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods for Social-Ecological Systems. London: Routledge, 2021.

Agonistic Design

- Create designs that provoke debate and highlight conflicts within society.

- Use design to surface and address contentious issues and power dynamics.

PocketPedal: The Movie, a participatory game to support co-design of urban cycling.

Holland, Alexander, and Stanislav Roudavski. “Mobile Gaming for Agonistic Design.” In Fifty Years Later: Revisiting the Role of Architectural Science in Design and Practice: The 50th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association, edited by Jian Zuo, Lyrian Daniel, and Veronica Soebarto, 299–308. Adelaide: Architectural Science Association, The University of Adelaide, 2016. https://doi.org/10/czsc.

Björgvinsson, Erling, Pelle Ehn, and Per-Anders Hillgren. “Agonistic Participatory Design: Working with Marginalised Social Movements.” CoDesign 8, no. 2–3 (2012): 127–44. https://doi.org/10/f24gm9.

Design Activism

- Use design as a tool for social and political change.

- Create projects that challenge the status quo and advocate for marginalized communities.

For some literature on design activism, see:

Busch, Otto von. Making Trouble: Design and Material Activism. Designing in Dark Times. London: Bloomsbury, 2022.

Fuad-Luke, Alastair. Design Activism: Beautiful Strangeness for a Sustainable World. London, UK: Earthscan, 2009.

Julier, Guy. “From Design Culture to Design Activism.” Design and Culture 5, no. 2 (July 2013): 215–36. https://doi.org/10/gc8zv3.

Thorpe, Ann. Architecture and Design Versus Consumerism: How Design Activism Confronts Growth. Abingdon: Earthscan, 2012.

Design Experiments

- Conduct experiments to test speculative designs in real-world settings.

- Use experimental methods to gather data and insights on the feasibility and impact of designs.

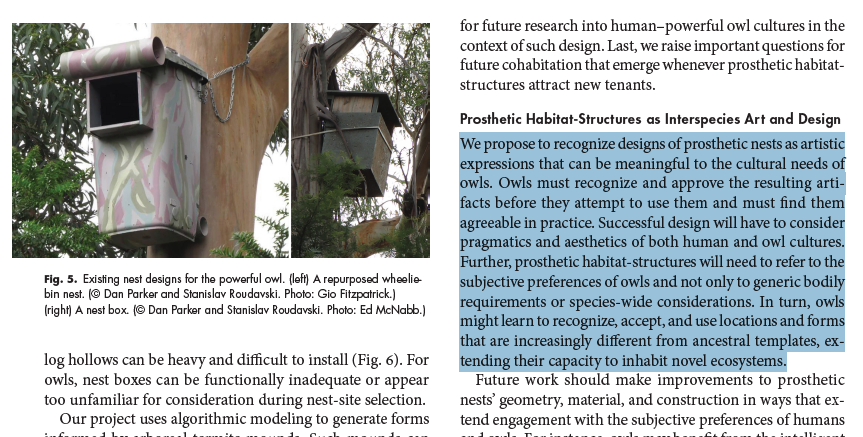

For our example of an interspecies design experiment, see:

Parker, Dan, Stanislav Roudavski, Bronwyn Isaac, and Nick Bradsworth. “Toward Interspecies Art and Design: Prosthetic Habitat-Structures in Human-Owl Cultures.” Leonardo 55, no. 4 (2022): 351–56. https://doi.org/10/hwkm.

For our example of artificial trees as design experiments aiming to learn from innovations developed by living trees, see:

Holland, Alexander, and Stanislav Roudavski. “Participatory Design for Multispecies Cohabitation: By Trees, for Birds, with Humans.” In Designing More-than-Human Smart Cities: Beyond Sustainability, Towards Cohabitation, edited by Sara Heitlinger, Marcus Foth, and Rachel Clarke, 93–128. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10/m7z3.

For our example of an approach to ecological design through a located data game framed as a design experiment, see:

Roudavski, Stanislav, Alexander Holland, and Julian Rutten. “Data Games for Ecological Design.” In Learning, Prototyping and Adapting, Short Paper Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), edited by Weixin Huang, Mani Williams, Dan Luo, and YiXin Wu, 115–20. Hong Kong: CAADRIA, 2018. https://doi.org/10/gfspv2.

Roudavski, Stanislav, Alexander Holland, and Julian Rutten. “Mould Racing, or Ecological Design through Located Data Games.” In Proceedings of the 24th International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA), edited by Rufus Adebayo, Ismail Farouk, Steve Jones, and Maleshoane Rapeane-Mathonsi, 193–200. Durban: Durban University of Technology, 2018. https://doi.org/10/czgc.

For a discussion of design experiments, see:

Felson, Alexander J., and Steward T. A. Pickett. “Designed Experiments: New Approaches to Studying Urban Ecosystems.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3, no. 10 (2005): 549–56. https://doi.org/10/dwfkkc.

Prototyping

In addition to traditional prototyping, which aims to refine and perfect a product, speculative and experimental prototypes are designed to provoke thought, stimulate discussion, and explore “what if” scenarios.

- Build prototypes of speculative designs to test and demonstrate ideas.

- Use low-fidelity and high-fidelity prototypes to explore different aspects of the design.

- Use prototypes as conversation starters to engage audiences in discussions about the future.

Role-Playing and Make-Belief

- Engage participants in role-playing exercises to experience speculative scenarios.

- Use simulations to explore the dynamics and consequences of future systems.

Communal Imagination, Workshops, and Co-Design

- Conduct workshops with stakeholders to collaboratively explore speculative ideas.

- Use co-design methods to incorporate diverse perspectives and insights.

Rich and Evocative Representation

- Use visualizations, films, and other media to communicate speculative concepts.

- Stage virtual, immersive and interactive environments to play through and explore the consequences.

Computational Modelling and Simulation

- Develop computational models to simulate future scenarios and systems.

- Use simulations to analyse the potential impacts and outcomes of design decisions.

Design Fiction

- Create fictional artefacts, scenarios, and prototypes to explore future possibilities.

- Use speculative objects to stimulate discussion and reflection.

Design fiction is the practice of creating prototypes of possible futures to expand the search space and assess consequences of decisions.

What Is Design Fiction?, a video introduction by NearFutureLaboratory

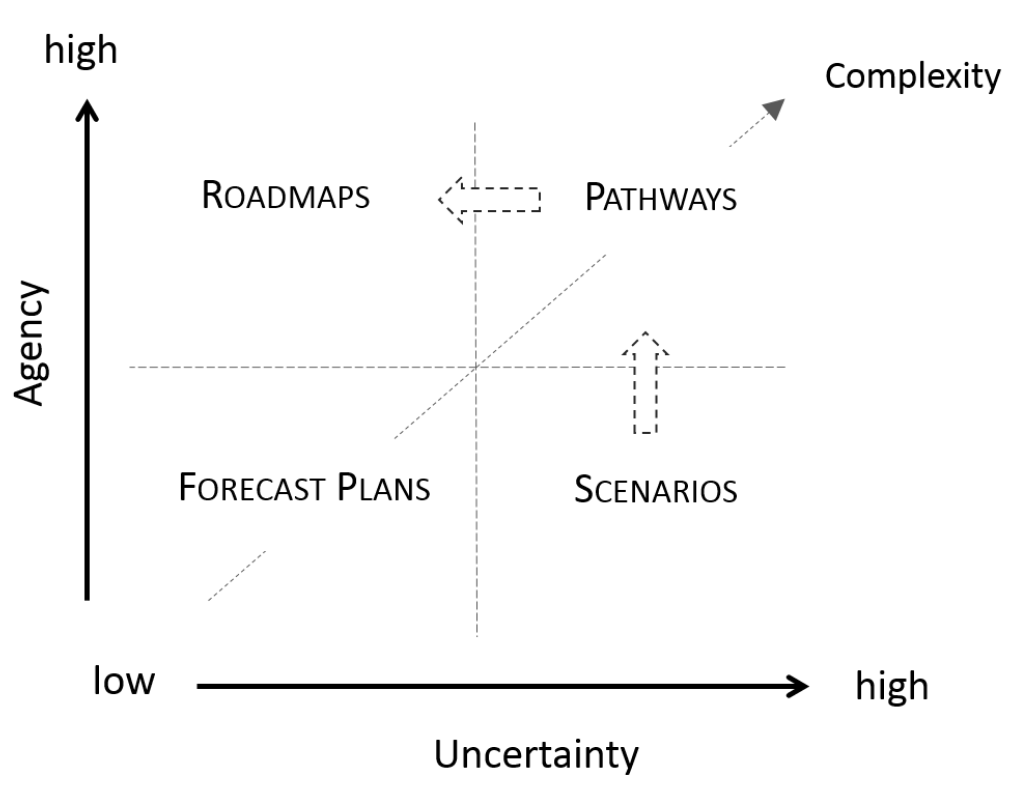

Scenario Building

- Develop detailed scenarios that describe potential futures.

- Use scenarios to explore the implications of different design choices.

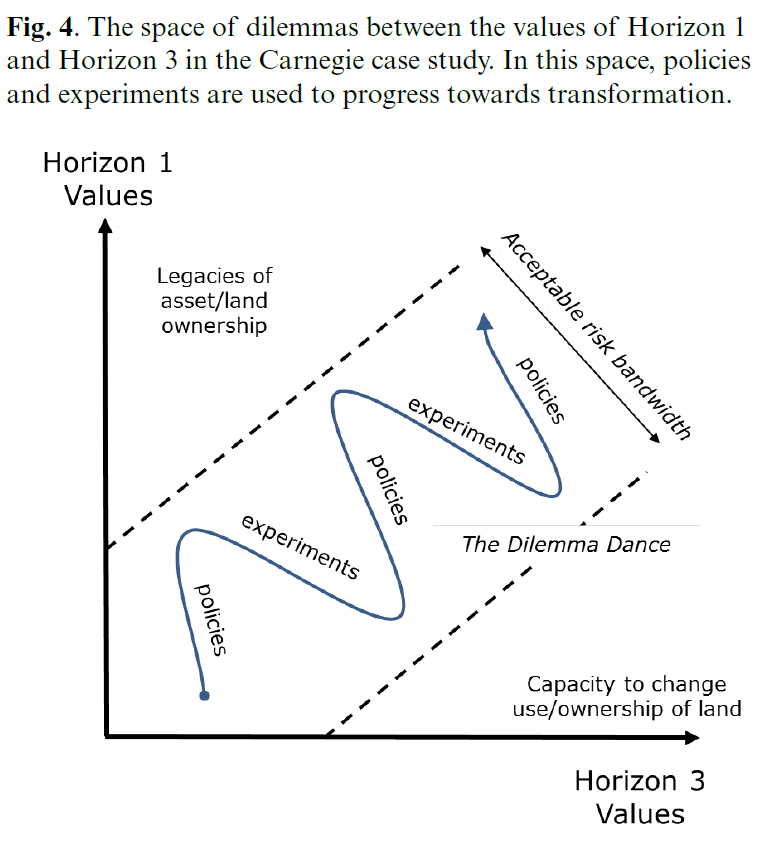

Global environmental change necessitates substantial changes in human and nonhuman individuals, institutions, societies, and cultures. Yet, research on practices for transformative change is less substantial than research on the nature of the problems.

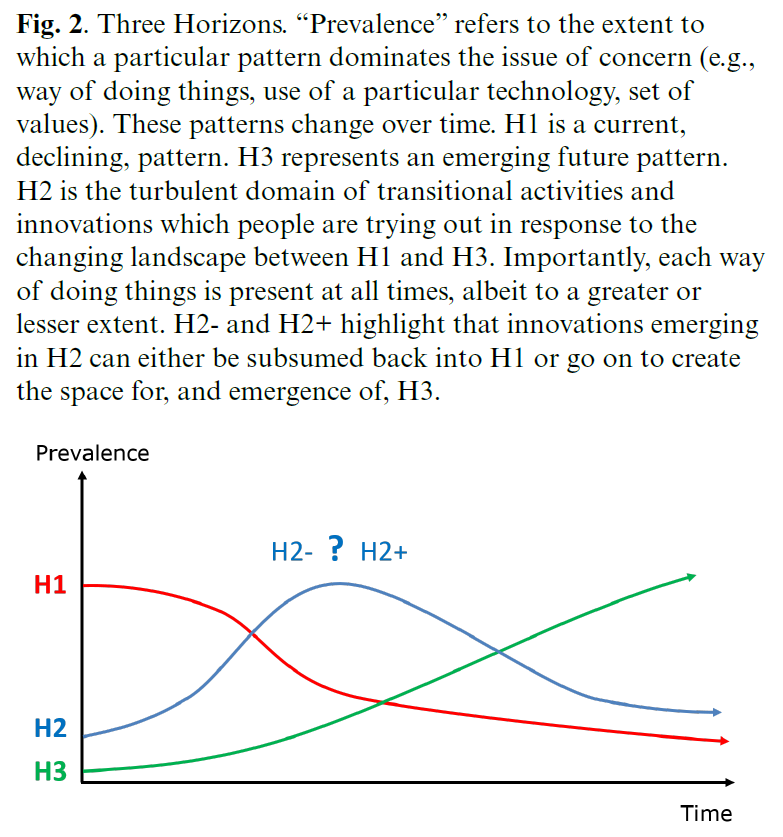

For example, the Three Horizons framework advocates the following:

- Providing a simple structure for working with complexity

- Helping develop future consciousness (an awareness of the future potential in the present moment)

- Helping distinguish between incremental and transformative change

- Making explicit the processes of power and patterns of renewal

- Enabling the exploration of how to manage transitions

- Providing a framework for dialogue among actors with different mindsets

Sharpe, Bill, Anthony Hodgson, Graham Leicester, Andrew Lyon, and Ioan Fazey. “Three Horizons: A Pathways Practice for Transformation.” Ecology and Society 21, no. 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10/gf636k.