Representation

Donoso, Alfonso. ‘New Politics: Sovereignty, Representation, and the Nonhuman’. In Global Changes: Ethics, Politics and Environment in the Contemporary Technological World, edited by Luca Valera and Juan Carlos Castilla, 45–55. Cham: Springer, 2020.

Donoso, Alfonso. ‘Representing Non-Human Interests’. Environmental Values 26, no. 5 (2017): 607–28. https://doi.org/10/gfspzh.

The foundational conditions of representation are to do with the disaggregated experience of the world by heterogenous agents. For example, all lifeforms experience the workld differently, due to species-, organism, community- specific subjectivities. All perceptions are also partial. Thus, in collectives, there is a need to transmit and translate information. There is also a need to do this compactly and reliably.

Definitions

Typical Objectives

- accurate transmission

- compact transmission

- intuitive transmission

- ability to resist errors in transmission

- translatable transmission

Typical Audiences

- self now

- self in the future (short, distant)

- self in diverse contexts with specific demands (exam, public presentation to a general audience, business or a competition pitch, persistent record for a website (personal site, company site, research group site, topical site, etc.))

- self as a holobiont (self as a part of a larger system, such as a family, a community, a society, an ecosystem, etc.)

- other selves, families, communities, societies, ecosystems, the biosphere

Trade-offs

This is a template table to map and compare types of representations.

Sender

An entity producing a representation.

Examples:

- a human mother asking her child to put on shoes (oral representation)

Intended Receiver

An entity senders have in mind or are evolved/constructed to address their representations to.

Examples:

- an architect designing a family home makes sketches and notes for the client family

| Sender | Intended Receiver | Context of Reception | Time | Objectives | Instruments | Gains | Costs | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Examples

- sketching as a way to think about complex problems, in design, in physics or mathematics, etc.

- writing notes as a way to aggregate knowledge on complex long-term problems, in all disciplines, in writing (writing as thinking)

Ethical Concerns

Cf. Ethics

- amplification of the less powerful voices

- resistance to bias

- preservation of diversity (geo, bio, cultural, etc.)

- long-term persistance

- economy and sustainability (example: how to minimise the costs of electronic information storage and transmission, the need to erase and forget)

- resilience in the face of change (example: how to tell future generations about nuclear waste storage facilities, the need to talk to unknown/imagined agents)

Types of 'Speakers' and 'Listeners'

Cf. Agent

- humans

- animals

- plants

- ecosystems

- communities

- machines

- organisations

Power Conditions

Cf. Power

Representation is always political because it happens in communities, between agents. This implies complex dynamic relationships with uneven distribution of needs, power, abilities, etc. Therefore, it is important to consider methods that account for power misbalances and seek to protect weaker voices.

For example, the dominant condition of today is the extractive economy or 'fossil capitalism'. This condition results in the structures of human societies that promote the market, jobs, and other action-structuring inventions that maximise activity and efficiency but distribute power and benefits unevenly. These structures also depend on the uncompensated destruction of the nonhuman world and warrant resistance on multiple grounds.

Types of Representation

By Sensory Ability

Visual representation Textual representation Aural representation

Political Representation

Cf. Biosemiotics. Political representation is still a system for transmitting meaning. For example, in a democratic system, it is a challenge of transmitting meanings from heterogenous groups, back to those groups (e.g., publics), to other groups (e.g., countries), into decisions (e.g., to legal entities, firms, bureaucracies).

Political considerations extend beyond humans and make additional difficult but also interesting challenges for representation. Non-human Democracy

Political Representation (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Political representation, on almost any account, will exhibit the following five components:

- Some party that is representing (the representative, an organization, movement, state agency, etc.);

- Some party that is being represented (the constituents, the clients, etc.);

- Something that is being represented (opinions, perspectives, interests, discourses, etc.); and

- A setting within which the activity of representation is taking place (the political context).

- Something that is being left out (the opinions, interests, and perspectives not voiced).

In addition to liberal ideas of representation as a delegate or trustee relationship, recent scholarship argues for other forms of representation for disadvantaged groups.

Mediation. Williams, Melissa. ‘The Uneasy Alliance of Group Representation and Deliberative Democracy’. In Citizenship in Diverse Societies, edited by Will Kymlicka and Wayne J. Norman, 124–53. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Advocacy. Urbinati, Nadia. ‘Representation as Advocacy: A Study of Democratic Deliberation’. Political Theory 28, no. 6 (2000): 758–86. https://doi.org/10/brm9rr.

For an overview, see Urbinati, Nadia, and Mark E. Warren. ‘The Concept of Representation in Contemporary Democratic Theory’. Annual Review of Political Science 11, no. 1 (2008): 387–412. https://doi.org/10/d8pxx2.

For forms of representations that concern nonhuman animals, see: Donaldson, Sue, and Will Kymlicka. Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Scientific Representation

Scientific Representation (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Science provides representations of atoms, elementary particles, polymers, populations, genetic trees, economies, rational decisions, aeroplanes, earthquakes, forest fires, irrigation systems, and the world’s climate. To a large degree, humans learn about the world through these representations. There are multiple accounts of scientific representation that describe how scientific models represent their target systems.

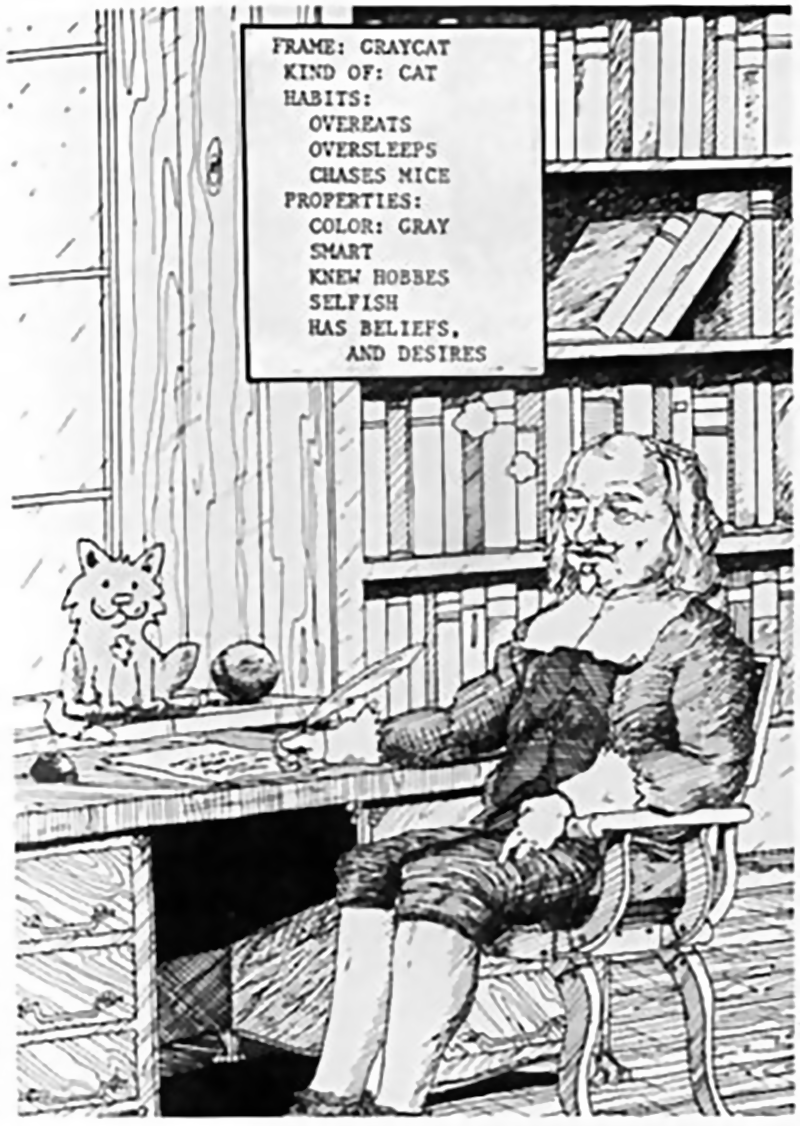

Mental Representation

The structure of mental representation is a topic of active debate in philosophy and science. Introduction to Mental Representation

Mental Representation (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

"'Representational Theory of Mind' that postulates the existence of semantically evaluable mental objects, including philosophy’s stock-in-trade mentalia – thoughts, concepts, percepts, ideas, impressions, notions, rules, schemas, images, phantasms, etc. – as well as the various sorts of “subpersonal” representations postulated by cognitive science."

"Such states are said to have “intentionality” – they are about or refer to things, and may be evaluated with respect to properties like consistency, truth, appropriateness and accuracy. (For example, the thought that cousins are not related is inconsistent, the belief that Elvis is dead is true, the desire to eat the moon is inappropriate, a visual experience of a ripe strawberry as red is accurate, an imaging of George Washington with dreadlocks is inaccurate.)"

Representation and Action

- The direct approach of representation focuses on the sensory side.

- Here, representations are internal reflections of external circumstances.

- They are destinations of sensory processes that translate the environmental state of affairs into a set of mental representations.

- However, an outward orientation also exists.

- Representations are the starting point for processes that lead to the external environment.

- This behavioural aspect of representation has received less attention.

- Behaviour is a phenomenon which is independent from mind. Ants, for example, behave even if it s not clear whether they have minds.

Keijzer, Fred A. Representation and Behavior. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Representation and Innovation

In humans, thinking requires representation.

Cf.

- representational talkback

- emergent information

- information/knowledge gardening

Design Representation

Definitions of Design Representation

Design representation makes ideas, innovations, and futures visible and shareable.

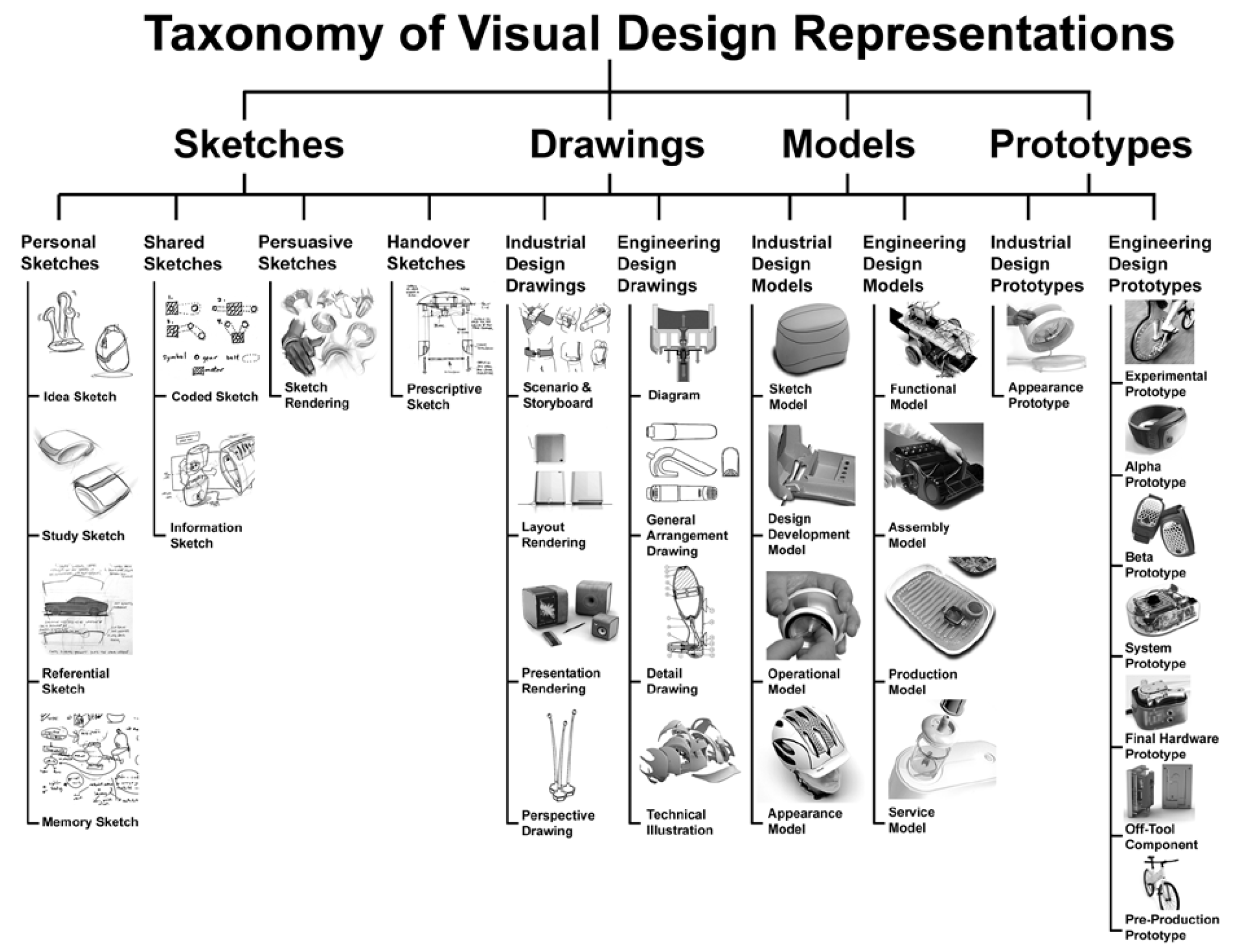

Taxonomies of Design Representation

Taxonomy of visual design representations in industrial and engineering design.

Pei, Eujin, Ian Campbell, and Mark Evans. ‘A Taxonomic Classification of Visual Design Representations Used by Industrial Designers and Engineering Designers’. The Design Journal 14, no. 1 (2011): 64–91. https://doi.org/10/cp5wjp.

Graphic Design

Representation is a process through which people make something that expresses an interest in some particular aspect of something else and that is motivated by both context and intent.

Representations may be expressions of intangible ideas, concepts, or feelings in some physical form (for example, a gesture, a drawing, or a poem). They may also communicate information about tangible objects, people, or places in the real world in a different physical form (for example, diagrams, photographs, or maps). And in other instances, one representational form may be substituted for another, such as a film for an oral history or a picture of five apples for the Arabic numeral 5.

The most basic unit of representation is the sign, which is something that stands for something else to someone in some respect.

"A depiction of something (an idea, concept, quality, person, place, thing, or event) in a form other than the one in which it originated; or, a process through which such forms are created that is motivated by context and intention."

Davis, Meredith. Graphic Design Theory. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012, 26.

Architecture

In a common understanding in architecture, representation in the design process is a visual testing of the results of the conceptual process that leads to the production of the intended object. Most architects rely on and most clients demand some visual verification of the concept, especially considering the enormous cost of materialising the concept.

Yates, Gabriela. ‘Distance and Depth’. In Design Representation, edited by International Design Thinking Research Symposium, Gabriela Goldschmidt, and William L. Porter, 3–36. London: Springer, 2004.

Parametric modelling is one form of design representation. Like any design representation, parametric modelling can be used towards several ends. "A motivation for many is form-finding, the use of a hypothesized external influence to guide the physical shape and material composition of a design. Form-finding is an extremely common strategy in engineering design, where the word optimization labels a specific formal device for discovery of utility-maximizing solutions to a set of constraints. In architecture, some of the best uses of the strategy have occurred in collaboration with engineering structural designers. Cf. Frei Otto, Cecil Balmond, Ove Arup, Edmund Happold.

Woodbury, Robert, Shane Williamson, and Philip Beesley. ‘Prarmetric Modelling as a Design Representation in Architecture: A Process Account’. 2006: Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA), 2011. https://doi.org/10/gk78x2.

Landscape Architecture

In landscape architecture, growth of plants is the main material. The key way to engage with this material is through direct action. Here, common uses of representation as for the description of design become hard or at least less prominent.

As Raxworthy discusses:

"Representation of plant material can only ever either specify a start or provide set reactions to predicted contingencies. Any specification for maintenance must predict potential situations; this makes it the same as the planting plan in that it simulates a future, even if that future is a catastrophic one.

However, if we accept that growth is the material of plants, such an approach to change is negative and pessimistic. Since a plant will never end up looking exactly as predicted, because each plant is a genetically different individual, emerging characteristics and traits during the growth process should be encouraged and engaged with. Nevertheless, representation will never be the key to this. Instead, real-time action in response to the plant, also known as gardening, provides a better tool to optimize serendipitous characteristics emerging from growth. Representation, where it is used, should instead be post-factum, as a means of documenting effects to allow for a learning process to inform later practice."

Raxworthy, Julian. Overgrown: Practices Between Landscape Architecture & Gardening. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

Representation and Decision-Making

Decision-making is the generalized form of design.

Key Types of Representation

- Different types of representation in human psychology

This is a book by a Nobel Prize winner on the noise or random deviation in human judgement but also in inter-human systems. His earlier book is even more relevant because it considers (in a simplified way) human decision making as an integration of two systems: System 1 (spontaneous, fast, effort-saving) and System 2 (attempting to be rational, slow and effortful).

Kahneman, Daniel, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment. London: William Collins, 2021.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Non-representation

Emphasise the embodied experience. Cf. Nigel Thrift

A critique of representation, especially in geography, particularly. Focuses on embodied practices which precede or exceed reflexive or cognitive understanding. Focuses on the role of the sensing body. Focuses on the now rather than on the after-stories.

Nonrepresentational Theory - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

References

Coppi, Alessia Eletta, Alberto Cattaneo, and Jean-Luc Gurtner. ‘Exploring Visual Languages Across Vocational Professions’. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training 6, no. 1 (2019): 68–96. https://doi.org/10/gpt3sv.

Dym, Clive L., and David C. Brown. Engineering Design: Representation and Reasoning. 2nd ed. 1994. Reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Bodker, Susanne. 1998. “Understanding Representation in Design.” Human–Computer Interaction 13 (2): 107–25. https://doi.org/10/dhqrz9.

Backlinks