Agent

This domain encompasses various types of agents that can act as stakeholders in design, research, politics, and law.

Cf.

- Agency

- Autonomy

- enactivism: cognitive processes occur in the world rather than solely in the mind. Perception, action, reflection, imagination, and mathematical reasoning exemplify skilful responses to affordances 1

- radical constructivism

Types of Agents

- genes and genotypes

- organisms and phenotypes

- species and higher taxa

- populations

- collectives, such as social groups, communities, families, and kinship groups

- ecosystems, including abiotic components

- hybrid entities, such as rivers, hills, or bioregions

- earth beings 2, a concept drawn from inclusive traditional-knowledge philosophies

- animal, vegetal, and mineral bodies

- ecological subjecthood 3

Relative Importance

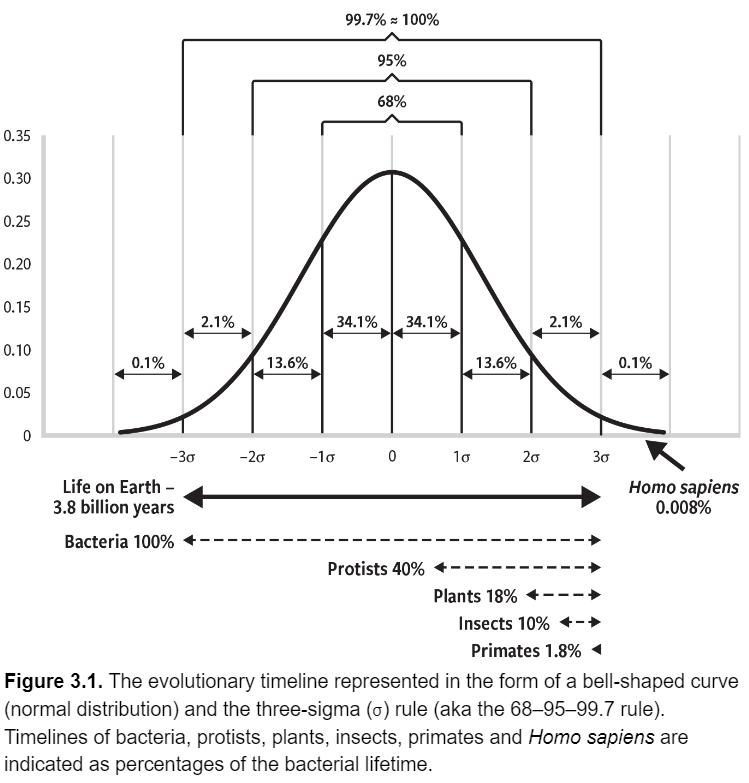

Homo sapiens are relatively insignificant in the "flow of Gaia" as a statistical outlier with an uncertain future.

Slijepcevic, Predrag. Biocivilisations: A New Look at the Science of Life. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2023.

Individuality

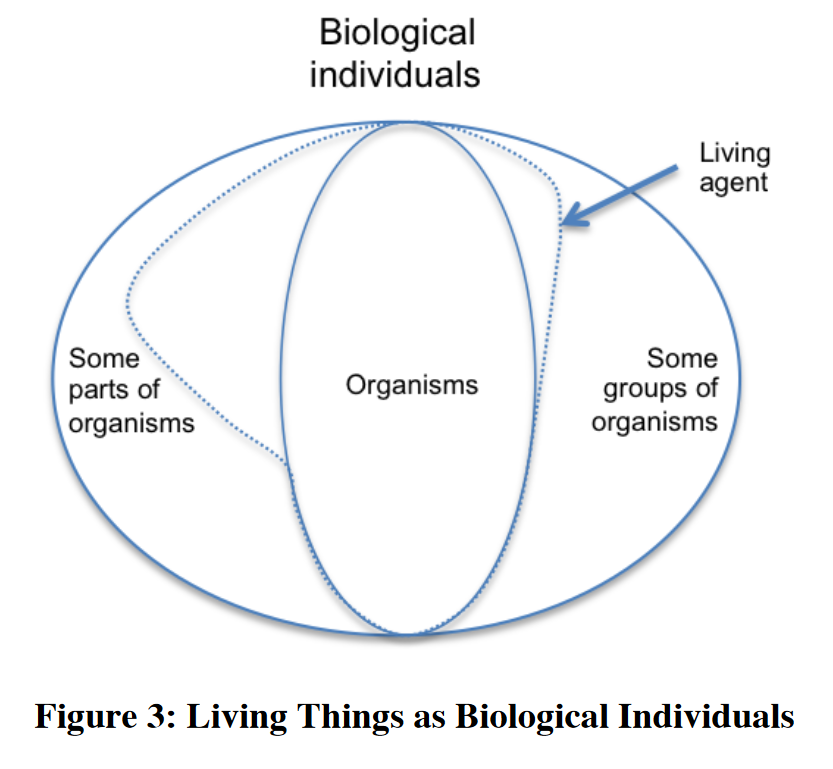

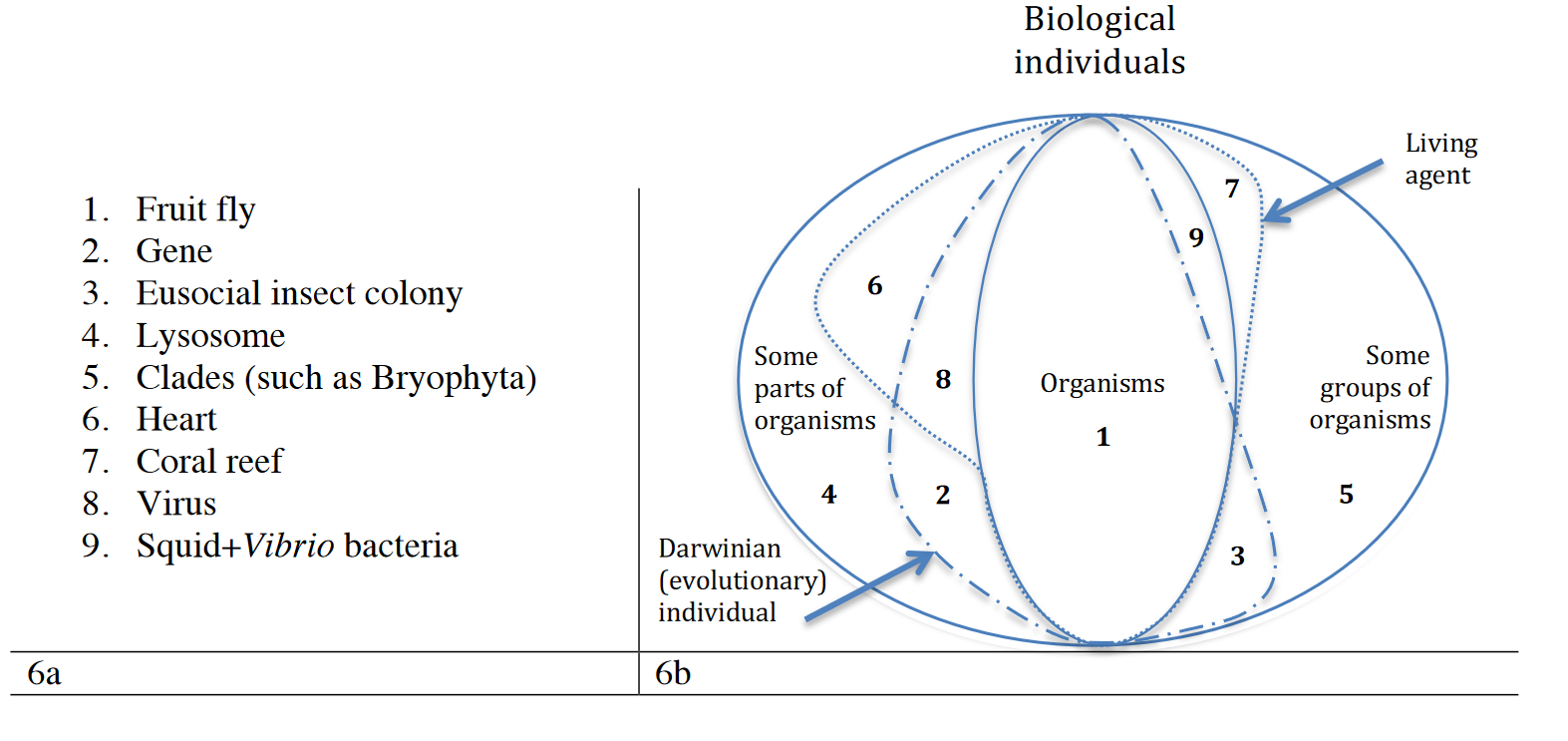

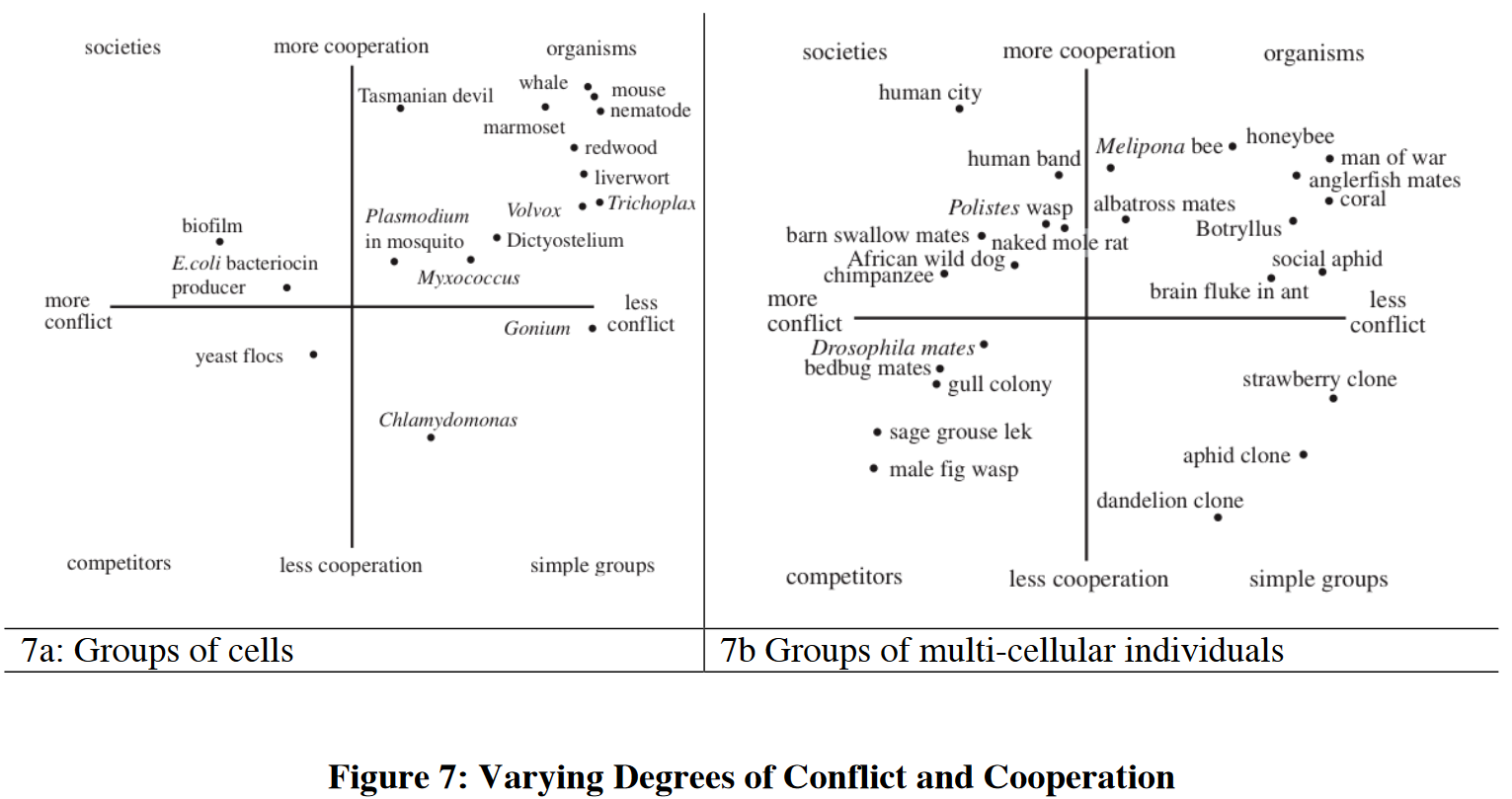

Biological individuality is a gradual property, and its nature remains debated. Individuality does not equate to an organism.

Some scholars consider the Earth’s Life (with a capital ‘L’)—that is, the Last Universal Common Ancestor and all its descendants—as a biological individual, analogous to the current understanding of species.

Mariscal, Carlos, and W. Ford Doolittle. ‘Life and Life Only: A Radical Alternative to Life Definitionism’. Synthese 197, no. 7 (2020): 2975–89. https://doi.org/10/gfvq4d.

The history of life is the history of constructing more complex biological individuals from simpler ones.

Some equate biological individuals with their life cycles, although this view is not widely accepted.

Queller, David C., and Joan E. Strassmann. ‘Beyond Society: The Evolution of Organismality’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364, no. 1533 (2009): 3143–55. https://doi.org/10/bzccvb.

Wilson, Robert A., and Matthew J. Barker. ‘Biological Individuals’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. 2007. Reprint, Stanford: Stanford University, 2019.

Perspectivism or Epistemological Pluralism

Cf.

Perspectivism refers to the idea that biologists may use contradictory terms to label phenomena associated with living beings, such as leaves or plants.

Epistemological pluralism recognises that no single approach or theory can capture the complexity and diversity of the world. Instead, multiple perspectives can complement and enrich one another. In contrast, monism asserts that only one valid way of knowing exists, while reductionism seeks to explain all phenomena in terms of a few basic entities or principles.

Related concepts include:

- as-if-ism: a philosophical practice of using models or hypotheses that are not literally true to explain or predict phenomena. For example, the atomic model as a solar system. Scientific theories serve as tools for organising and manipulating observations, rather than as true descriptions of reality 4

- scientific pluralism: the view that science is not unified in its metaphysics, epistemology, research methods, or models

- conceptual nominalism: the world consists of singular and particular things. Universals are mental representations, a middle position between extreme nominalism (which denies similarities between particulars) and realism (which asserts that universals exist independently of particulars) 5

- map analogy: concepts relate to reality as maps relate to landscapes. Maps are useful for navigation but are partial, and multiple different maps are possible 6

- epistemological anarchy (or "anything goes"): a conception by Feyerabend, who argued against the unity of the scientific method. He reasoned that multiple approaches are more likely to support creativity. Multiple theories and methods can coexist and compete without the need to judge them against a single truth 7

- epistemic pluralism 8

- legal pluralism

Subnotes

- Amphibians

- Animals

- Beaver

- Birds

- Cell

- Companion Animals

- Cow

- Coyote

- Dog

- Fire

- Fish

- Fungi

- Grey Box

- Ice

- Insects

- Koala

- Mangrove

- Microbe

- Near Surface Ecologies

- Owl

- Oyster

- Personhood

- Pigeon

- Plant

- Soil

- Spiders

- Turtle

- Water

- Whale

Footnotes

Gallagher, Shaun. Enactivist Interventions: Rethinking the Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.˄

Cadena, Marisol de la. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean Worlds. 2011. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.˄

Davies, Emma Shea. “Ecological Subjecthood.” PhD Thesis, The Australian National University, 2019.˄

Vaihinger, Hans. The Philosophy of ’As If: A System of the Theoretical, Practical and Religious Fictions of Mankind. Translated by Charles K. Ogden. 2011. Reprint, Mansfield Center: Martino, 2009. Just the original use of the term, there are recent publications and debates on this.˄

Panaccio, Claude. ‘Nominalism and the Theory of Concepts’. In Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science, edited by Henri Cohen and Claire Lefebvre, 2nd ed., 1115–33. 2005. Reprint, San Diego: Elsevier, 2017.˄

Woodger, Joseph H. Biological Principles: A Critical Study. New York: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1929.˄

Feyerabend, Paul. Against Method. 3rd ed. 1975. Reprint, London: Verso, 1993.˄

Carter, J. Adam, and Anne-Kathrin Koch. ‘Epistemic Pluralism’. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs, edited by Phil Harris, Alberto Bitonti, Craig S. Fleisher, and Anne Skorkjær Binderkrantz, 1–4. Cham: Springer, 2020.˄

Backlinks