Ladder

Cf.

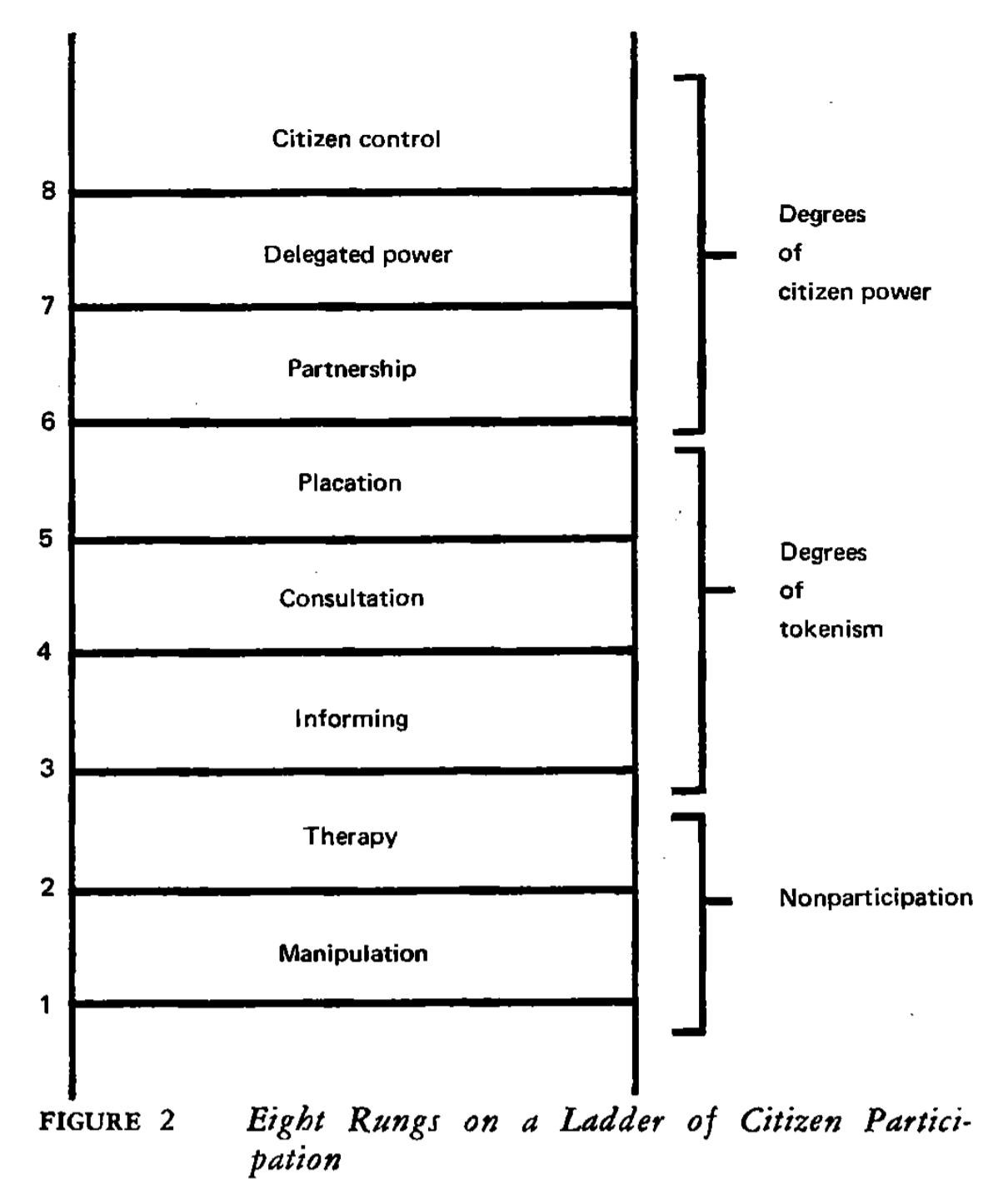

Sherry Arnstein published her seminal article "A Ladder of Citizen Participation" in the Journal of the American Institute of Planners in 1969.

- Metaphor: a ladder with eight rungs describing varying levels of citizen power.

- Lower rungs: "nonparticipation" (manipulation and therapy).

- Middle rungs: "tokenism" (informing, consultation, and placation).

- Upper rungs: "citizen power" (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control).

- Origin: developed from Arnstein's experience with US federal social programmes (anti-poverty, urban revitalisation).1

- Influence: remains one of the most influential conceptual tools; widely applied in urban planning, health, environmental management, education, smart city governance, and multispecies design.

Lauria, Mickey, and Carissa Schively Slotterback, eds. Learning from Arnstein’s Ladder: From Citizen Participation to Public Engagement. New York: Routledge, 2020.

Framework Evolution

- Scope expansion: influenced participatory design, citizen science, and co-creation models.

- Smart cities: shift from hierarchical models to networked participation, emphasising data sovereignty and techno-politics.2

- Health & transport: integrates co-governance and co-creation, promoting equal roles for all actors.3

Limitations and Criticisms

- Arnstein's self-critique:

- Power is not distributed as neatly as the rungs suggest.

- Real-world complexity might require 150 degrees of gradation.4

- Omitted roadblocks: racism, paternalism, resistance from powerholders, and the disorganisation of low-income communities.

- Bureaucratic tokenism: legal mandates often fail to deliver genuine empowerment.5

- Structural flaws (Tritter & McCallum):

- "Missing rungs, snakes, and multiple ladders."6

- Fails to differentiate method, user category, and outcome.

- Ignores prerequisites (trust, capacity building, establishing consensus around agendas).

- Ignores the balance between participation intensity and population breadth.

- Context & purpose (Collins & Ison):

- Focus on power is insufficient; the ladder is devoid of context ("a ladder must lean against something").

- Provides no means of making sense of the context in which it is used.

- Fails to address what participation is for.7

- Risks of control:

- "Tyranny of the majority" may disadvantage minorities.

- Delegation does not automatically ensure control (and questions if "control" is what one wants).6

- Oversimplification: presents a linear hierarchy, ignoring iterative and context-dependent processes.8

- Narrow focus: focuses on power redistribution, neglecting cultural, social, and technological dimensions.9

- The "Arnstein Gap" (Bailey & Grossardt):

- Measures the difference between experienced and desired participation.10

- Consistent across 25 countries: citizens and professionals aspire to Partnership (Level 6), not Citizen Control (Level 8).

- Suggests complete redistribution of decision-making power is neither desired nor useful.

- Transitional justice: fails to convey the complexity, notions of power, agency, space, and engagement of victims and affected communities.11

Redesigns

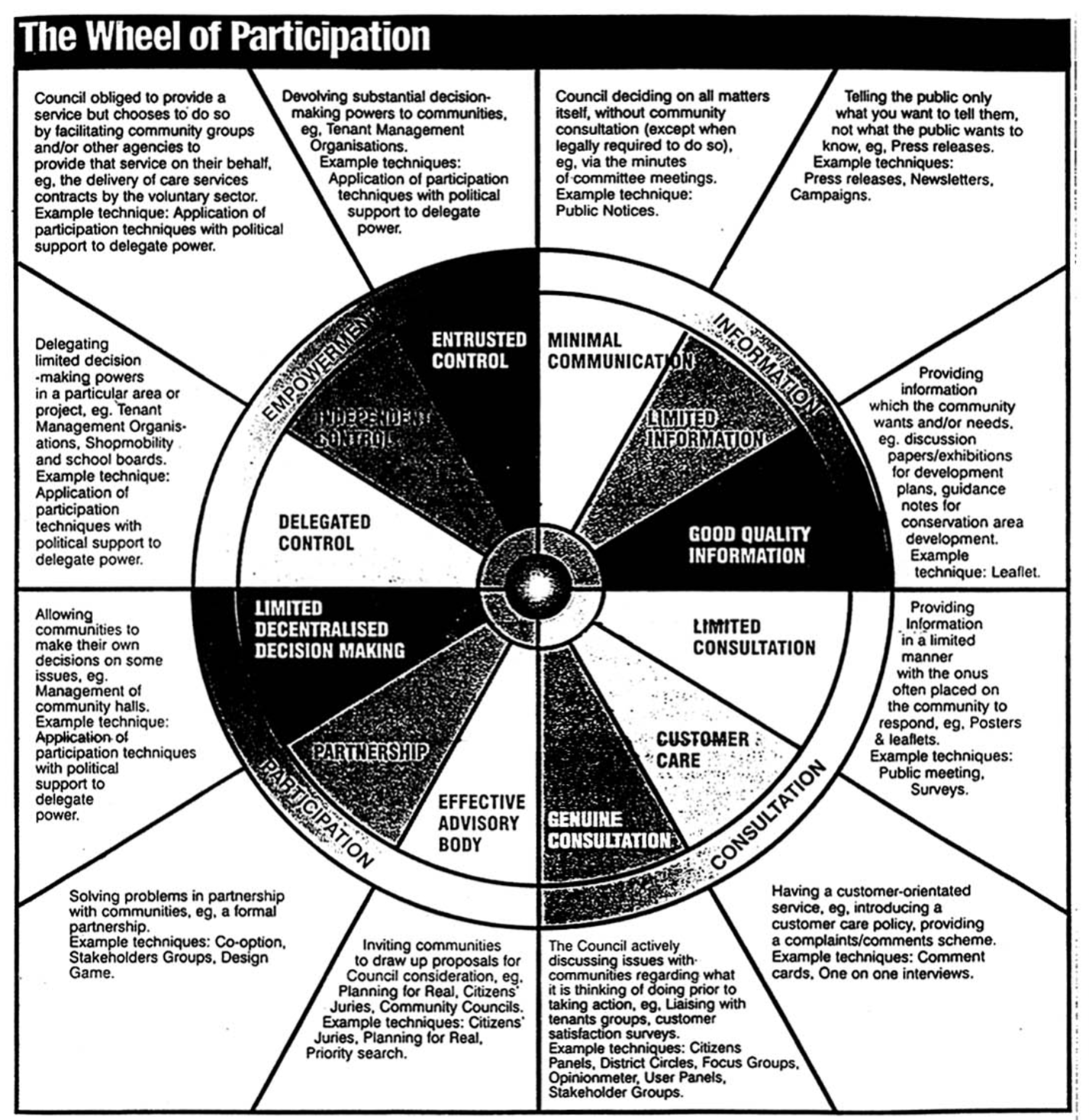

- Wheel of Empowerment: Davidson, S. (1998).

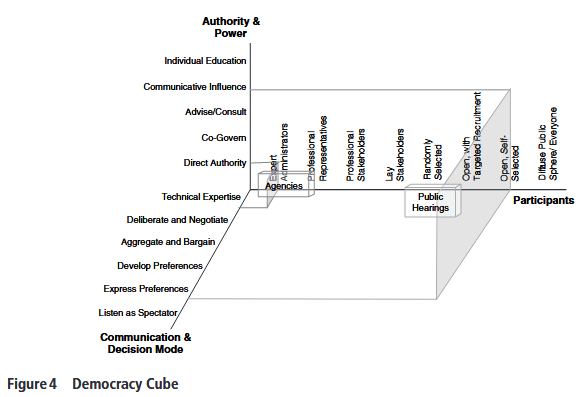

- Democracy Cube (Fung): adds participant selection and communication mode to the power dimension.12

- Mosaic (Tritter & McCallum): captures complex, dynamic relationships between users, communities, voluntary organisations, and governance systems. Illustrates how diverse elements integrate. (Criticised for lacking visual illustration/methodology, validating Arnstein's simplicity).13

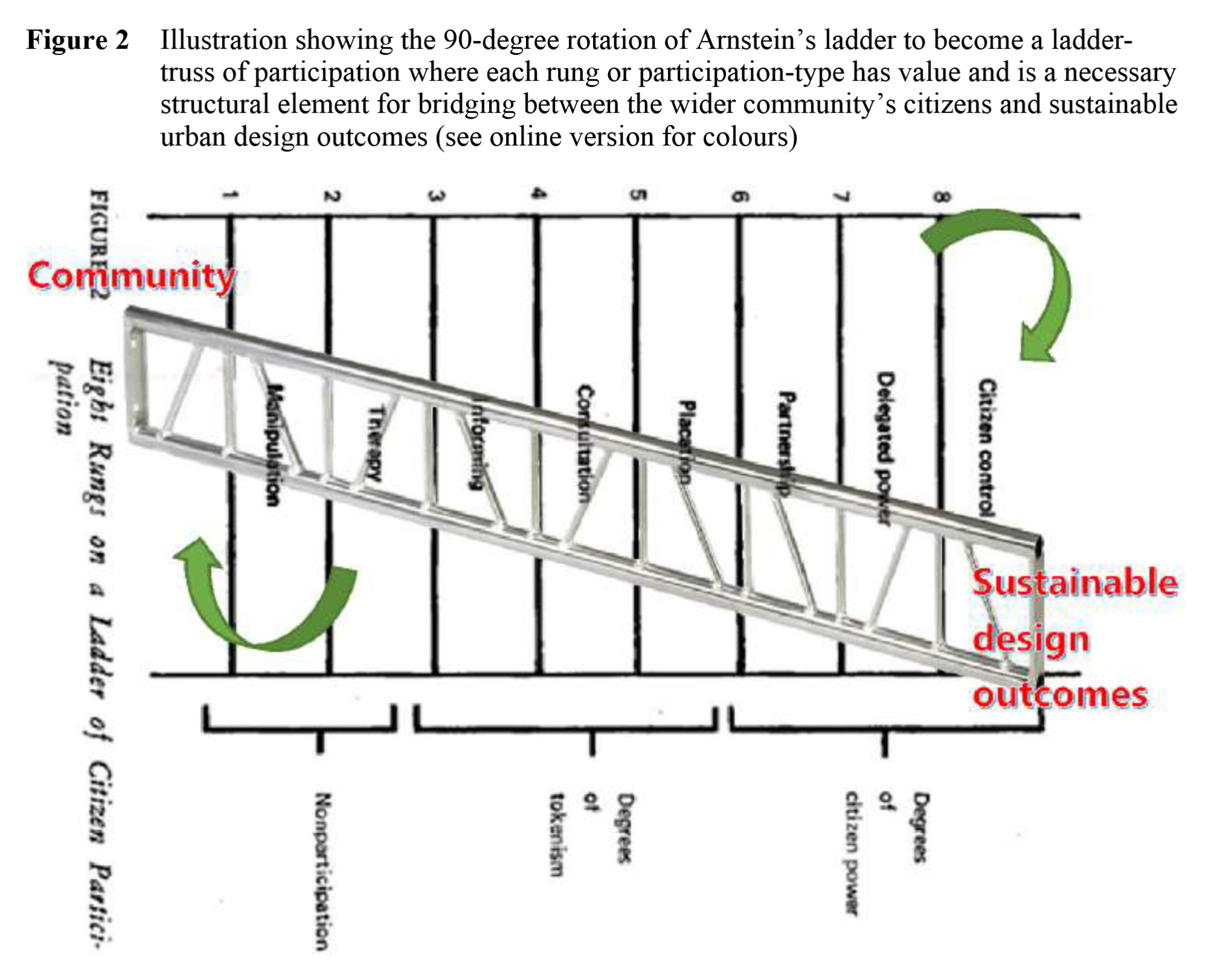

- Ladder-Truss (White & Langenheim):

- Rotates framework 90 degrees.

- All rungs are equally important structural elements bridging community needs and design outcomes.

- Reframes "manipulation" as skilful presentation of sustainability issues/trade-offs.14

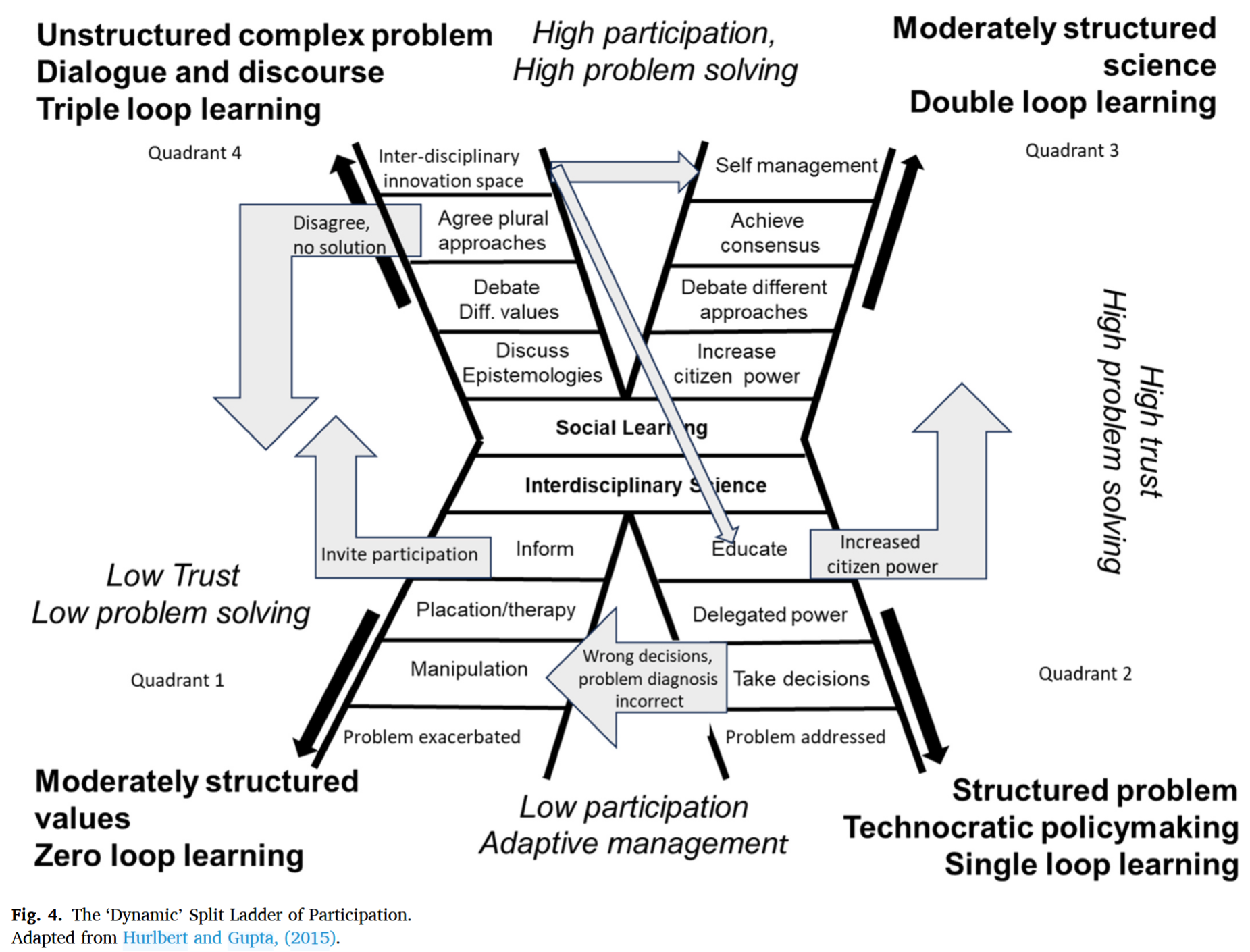

- Dynamic Split Ladder (Hurlbert & Gupta):

- Incorporates single, double, and triple-loop learning (transformational change, engaging uncertainty in science and values).15

- Participation needs vary by problem structure (structured vs unstructured).

- Moves beyond "more participation is better"; extensive participation may be unnecessary if science/values are agreed.

- Revised after eight years; applied in environmental science, water, energy, health, and education.

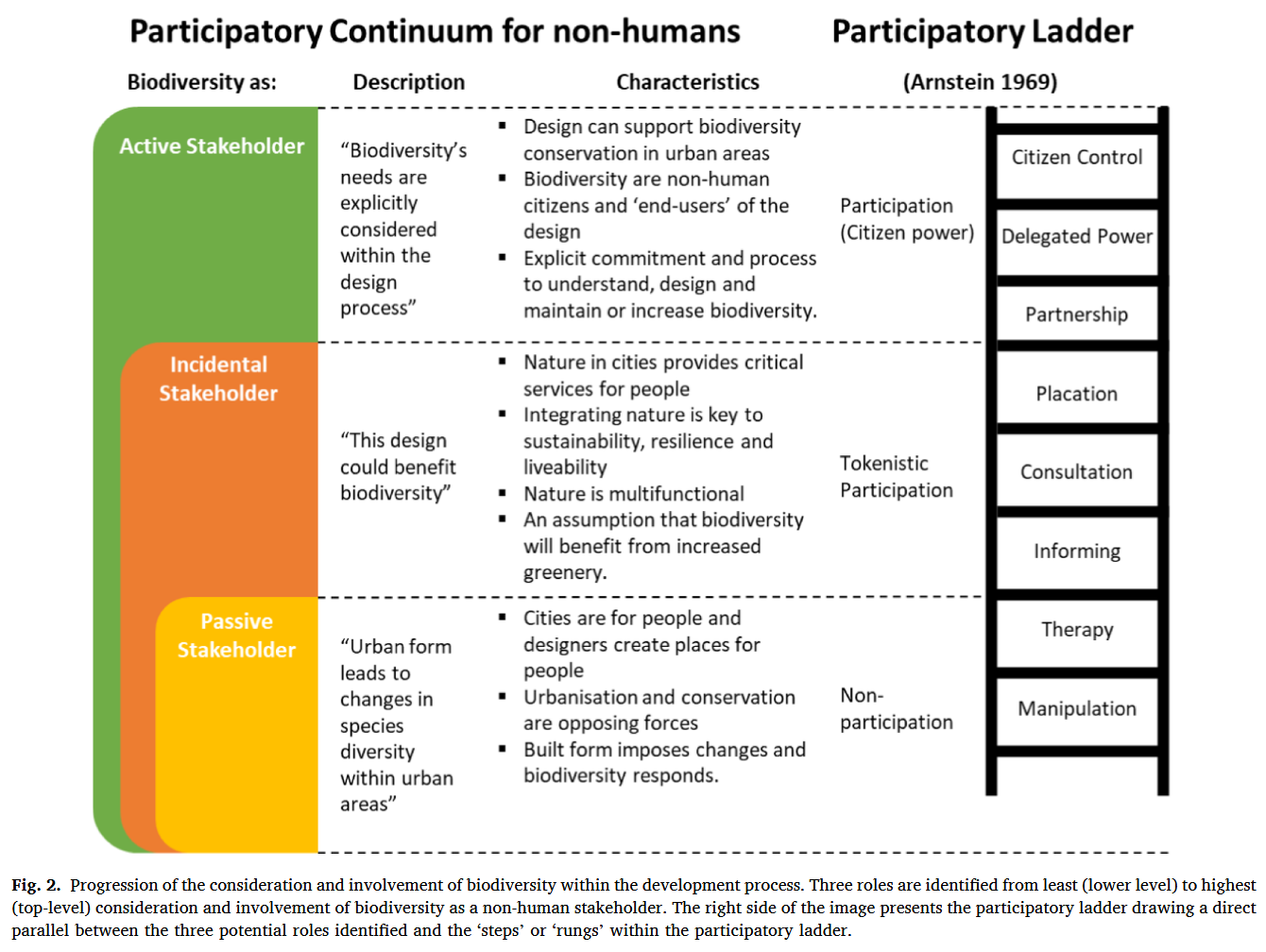

Biodiversity and Nonhuman Relations

- Biodiversity: human-driven consideration of non-human stakeholders.16

- Legitimacy of biosphere reserves.17

- Citizen participation in governance of nature-based solutions.18

- Stakeholder participation in environmental management.22

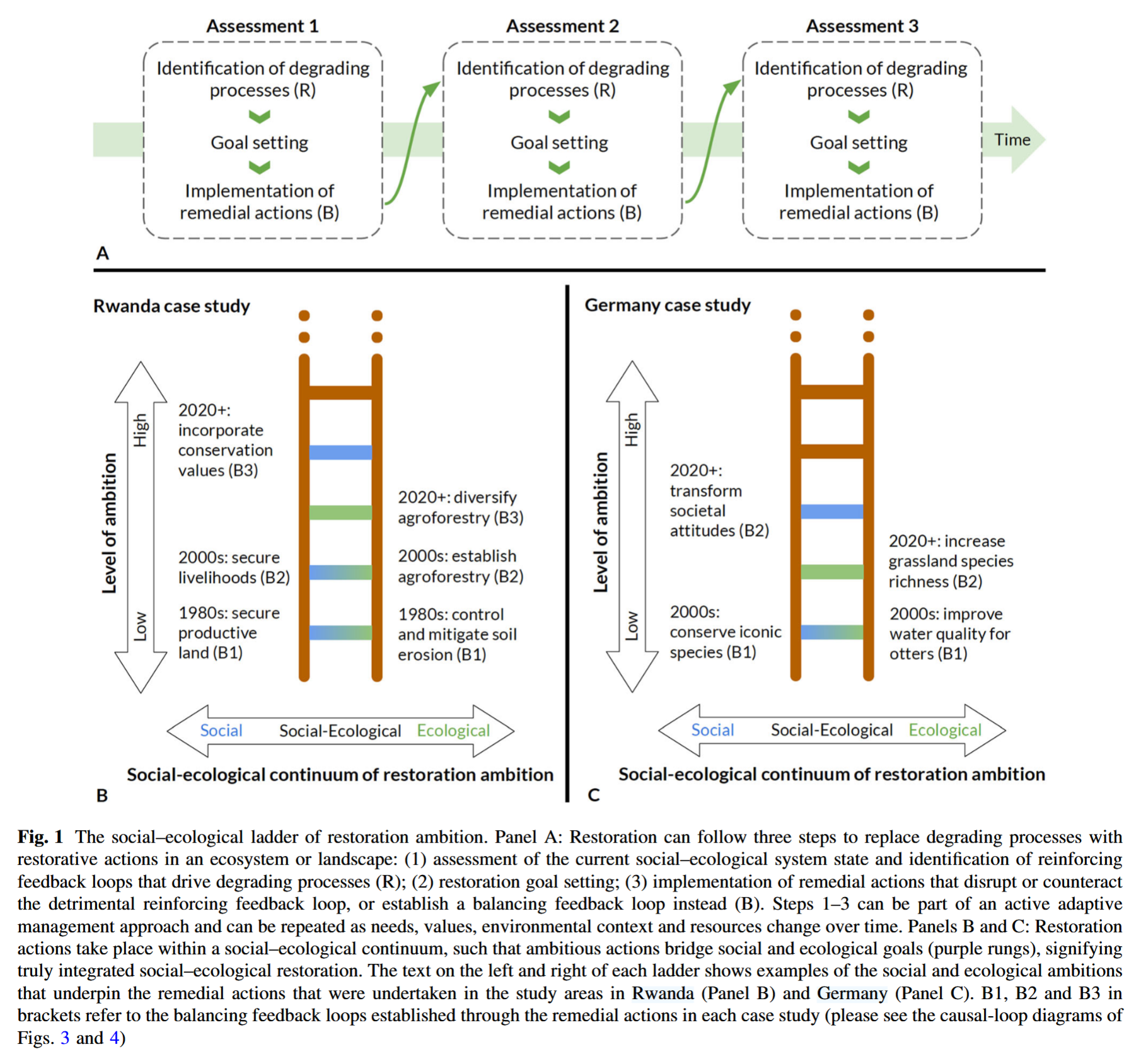

- Social-Ecological Ladder (Frietsch et al.): integrates participatory methods with adaptive management (causal loops, scenario planning) for restoration ambition and long-term projects.19

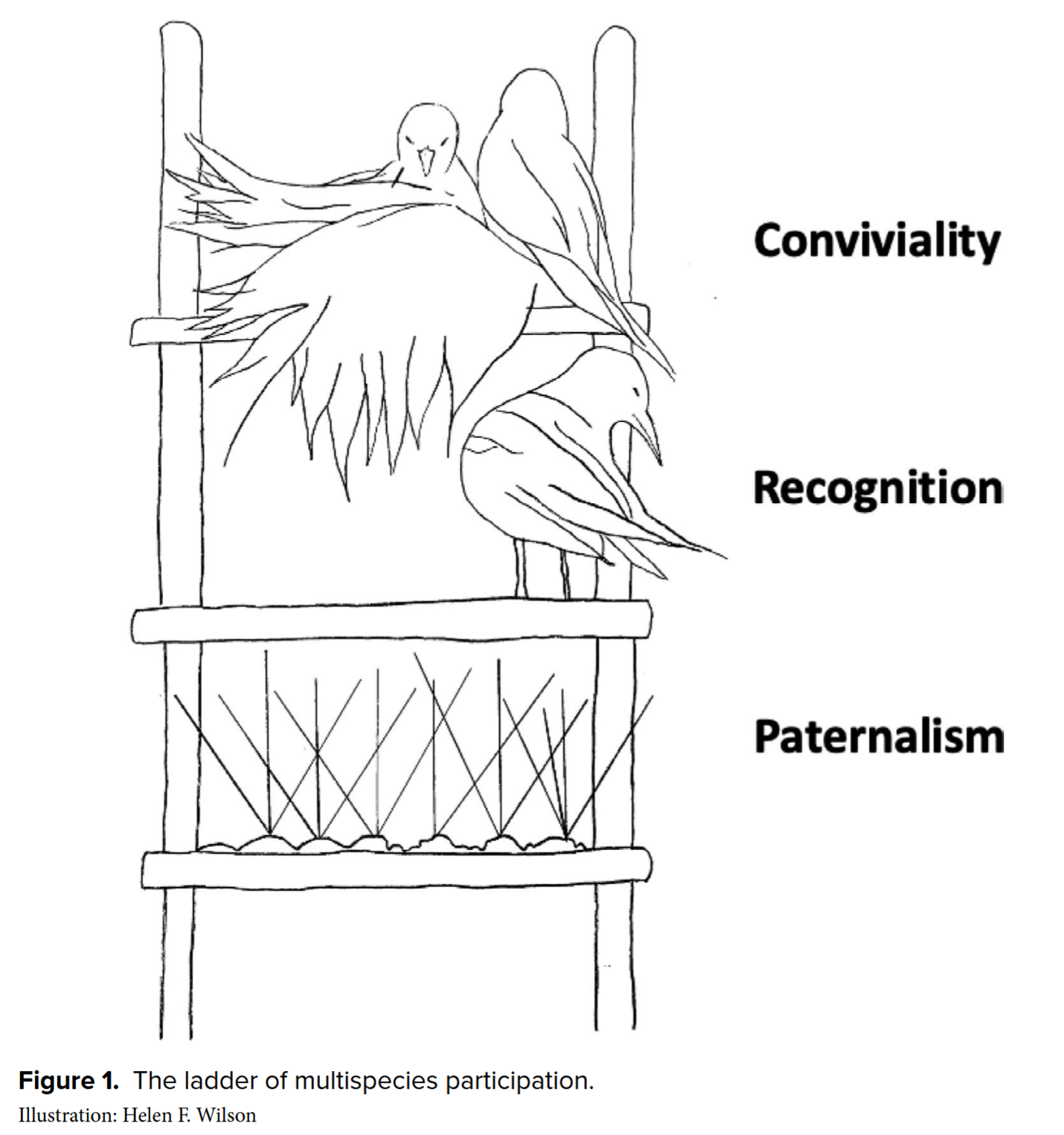

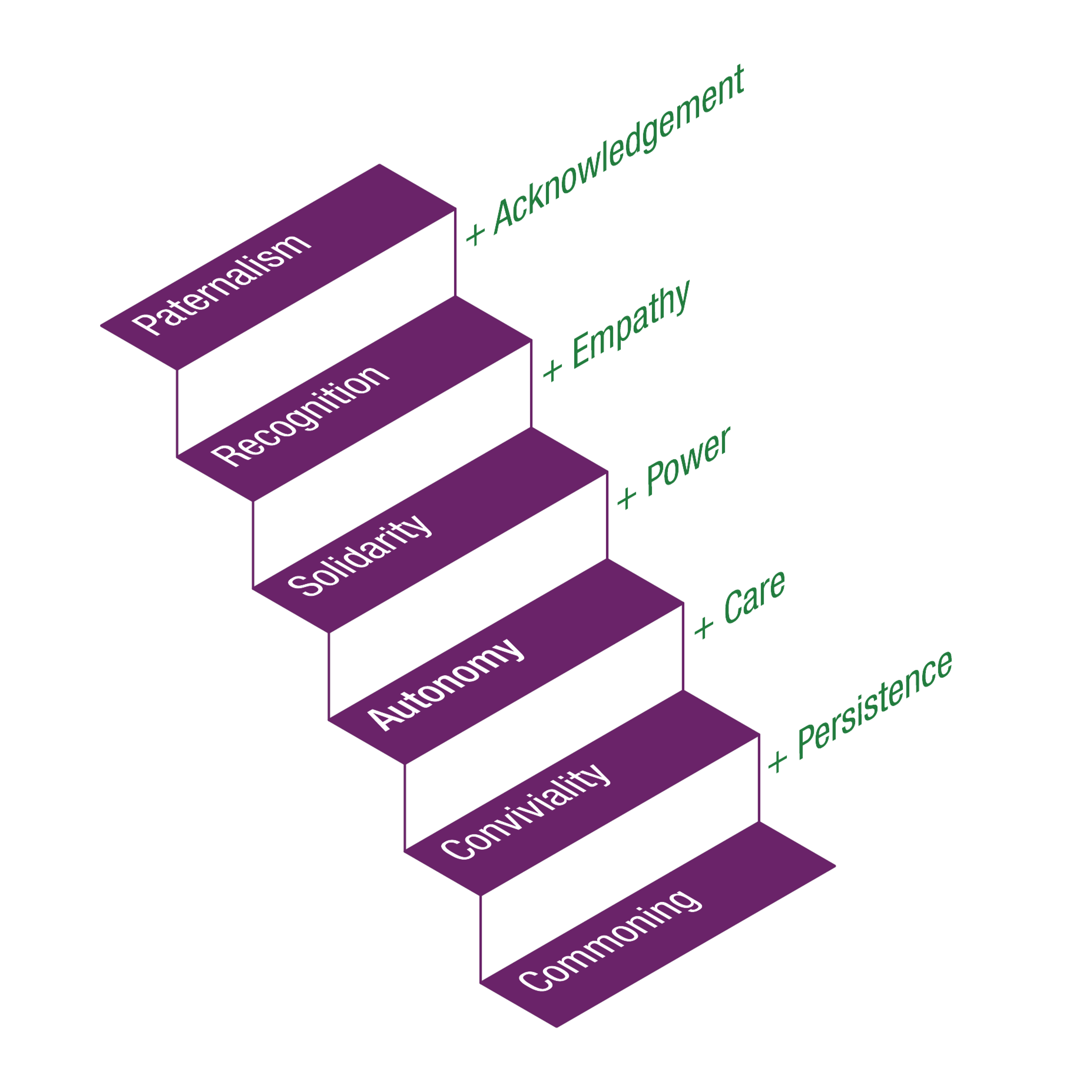

- Ladder of Multispecies Participation (Førde et al.):

- Specifically for urban planning; examines how planners can become better attuned to how other species make place.

- Case study: kittiwakes in Norwegian cities.

- Bottom: paternalism (exclusion/deterrents).

- Middle: recognition (acknowledging nonhuman presence).

- Top: conviviality (the "messy business of living together").20

The Ladder of More-Than-Human Participation

Roudavski, Stanislav. “The Ladder of More-than-Human Participation: A Framework for Inclusive Design.” Cultural Science 14, no. 1 (2024): 110–19. https://doi.org/10/g8nn27.

Advantages

- Metaphor: inherits the ladder but shifts focus from political/legal power.

- Purpose: explicitly aims for health, wellbeing, and thriving.

- Context: Collins and Ison argue that Arnstein's ladder is devoid of context and has no means of making sense of the context in which it operates. Roudavski grounds the ladder in evolutionary and planetary community dynamics such as niche construction and symbiosis, providing a "wall" for the ladder to lean against.

- Translation: allows for communications and transpositions beyond a single understanding of power.

- Knowledge creation: Collins and Ison propose social learning as an alternative to power struggles. Roudavski aligns with this by framing participation as collective problem-solving through recognition, solidarity, and commoning.

- Goal reframing: Arnstein positions "citizen control" as the top rung. Roudavski replaces this with "commoning," emphasising persistence and care over domination.

- Temporal scales: Holland and Roudavski note that human cultures typically operate on shorter time scales. Roudavski's ladder accommodates both fast changes such as microorganism evolution and slow processes such as forest formation.

- Non-adversarial: Tritter and McCallum criticise Arnstein for framing participation as a zero-sum contest between two parties wrestling for control. Roudavski redefines autonomy as conviviality, blending autonomy with care rather than competition.

- Multiple expertise: Tritter and McCallum call for complementarity between forms of knowing rather than hierarchy. Roudavski recognises nonhuman beings as capable of innovation and design leadership, as demonstrated in work by Rutten, Holland, and Roudavski on plants as designers.

- Justice orientation: Roudavski draws on Baxter's theory of ecological justice and Donaldson's work on animal citizenship to move from charity to justice, calling for political recognition of nonhuman rights.

- Hybrid Geographies: Cloke and Jones argue that nonhuman agency often manifests as Resistance to human ordering (e.g., trees disrupting cemetery boundaries).21 This suggests that "participation" is not always a cooperative act invited by humans, but an inherent capacity of the nonhuman to alter shared spaces.

Limitations

- Simplification: Førde and colleagues acknowledge that Roudavski's model, like Arnstein's original, remains a reductive abstraction of complex processes.

- Heuristic status: a tool for thinking, not a complete description of reality.

- Empirical testing: requires validation through practical application.

- Scepticism: Roudavski acknowledges the approach faces criticism as naïve or impractical given perceived human selfishness.

- Causality: Roudavski notes difficulty demonstrating benefits within complex systems, especially when advantages fall outside human perceptual scales.

- Complexity: Roudavski observes that engaging in more-than-human design increases project difficulty in team composition, communication, and goal setting.

- Conflict: Roudavski recognises heightened likelihood of disagreements between diverse life forms with incompatible needs.

- Knowledge gaps: Roudavski identifies the profound lack of knowledge about nonhuman systems as a complication for planning.

- Human interests: Roudavski concedes the approach may require counterintuitive curtailment of short-term human priorities.

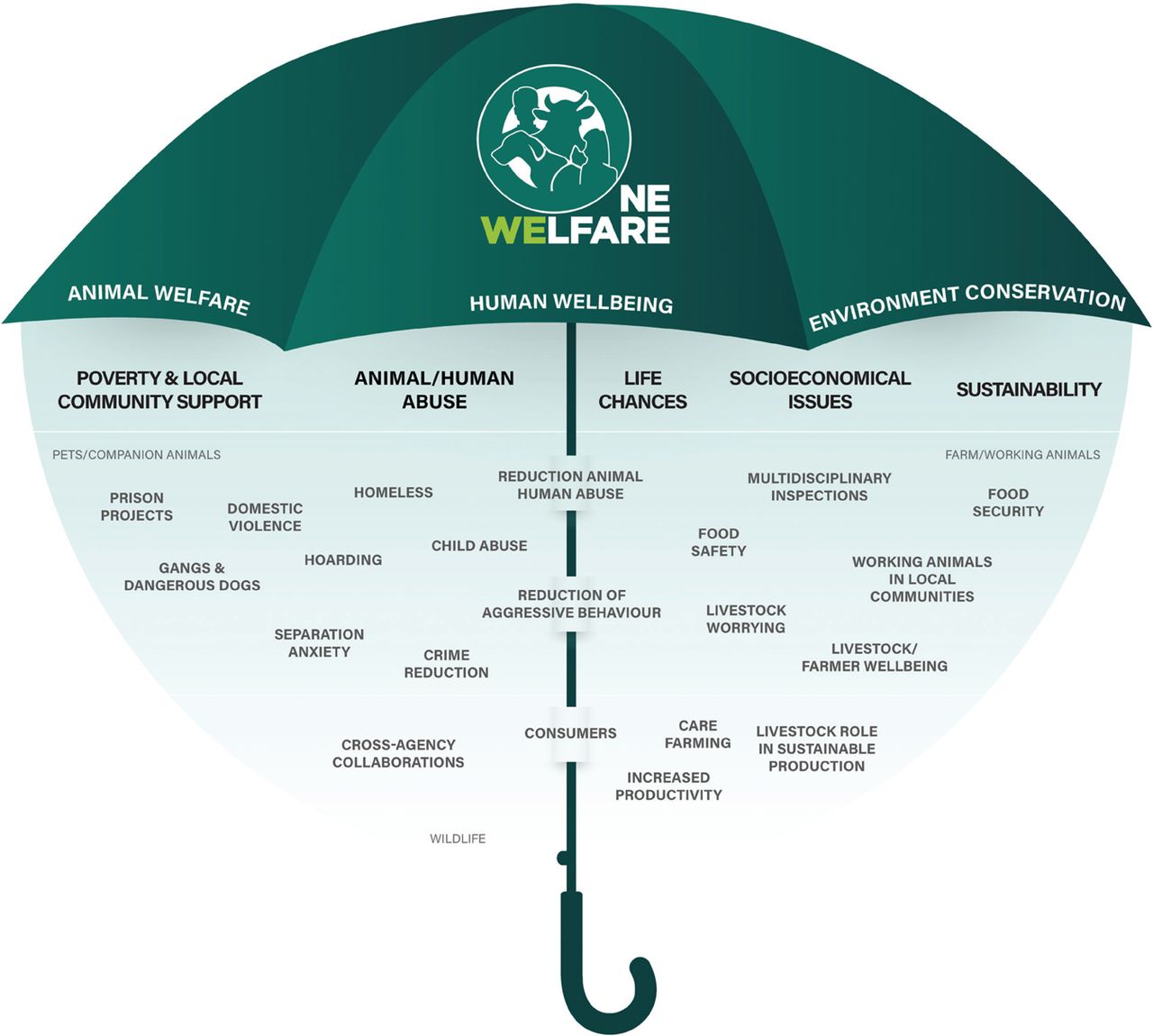

Solidarity

- Interspecies empathy: Elisa Aaltola notes emotions are socially constructed, opening paths to solidarity.

- One Welfare: extension of the One Health approach (cf. Health).

What is ‘One Welfare’? – RSPCA Knowledgebase

Pinillos, R. García, Michael C. Appleby, Xavier Manteca, Freda Scott-Park, Charles Smith, and Antonio Velarde. ‘One Welfare: A Platform for Improving Human and Animal Welfare’. Veterinary Record 179, no. 16 (2016): 412–13. https://doi.org/10/gfspxp.

Commoning

Rockström, Johan, Louis Kotzé, Svetlana Milutinović, Frank Biermann, Victor Brovkin, Jonathan Donges, Jonas Ebbesson, et al. “The Planetary Commons: A New Paradigm for Safeguarding Earth-Regulating Systems in the Anthropocene.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, no. 5 (2024): e2301531121. https://doi.org/10/gtfk3h.

Transformation

- Aggregates transitions between ladder steps.

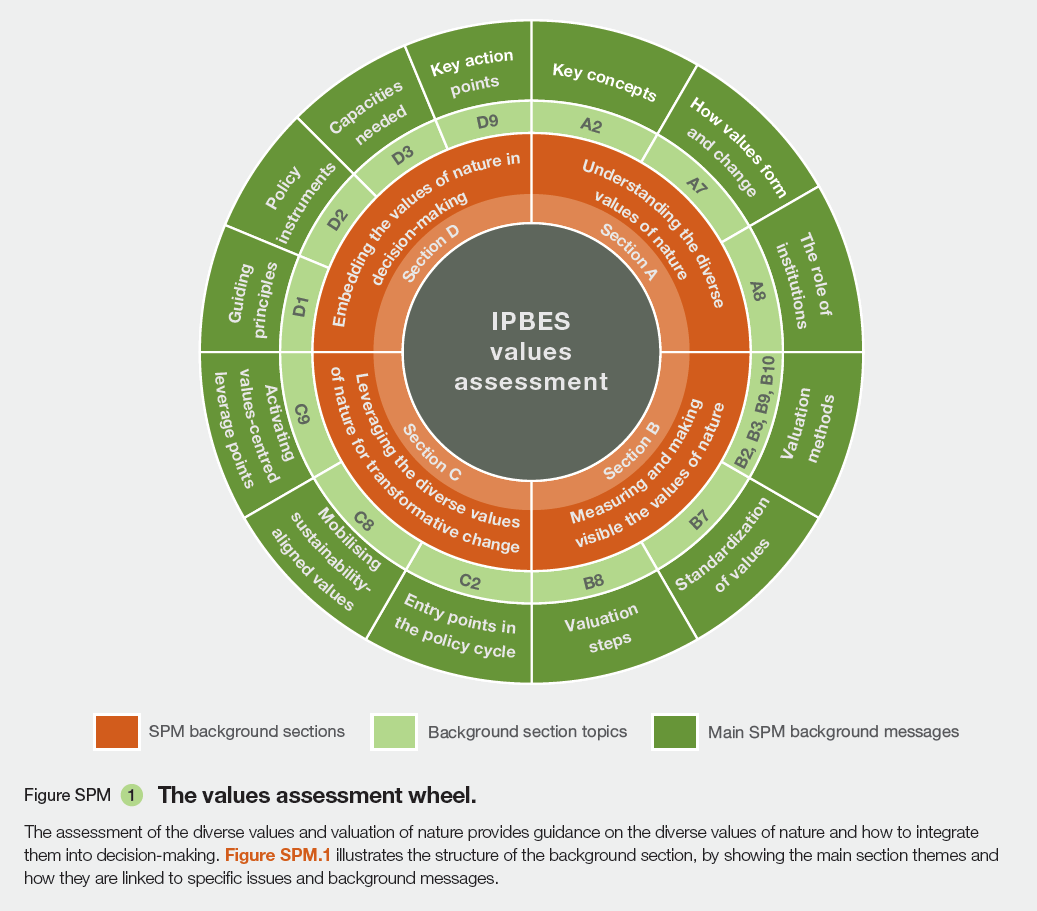

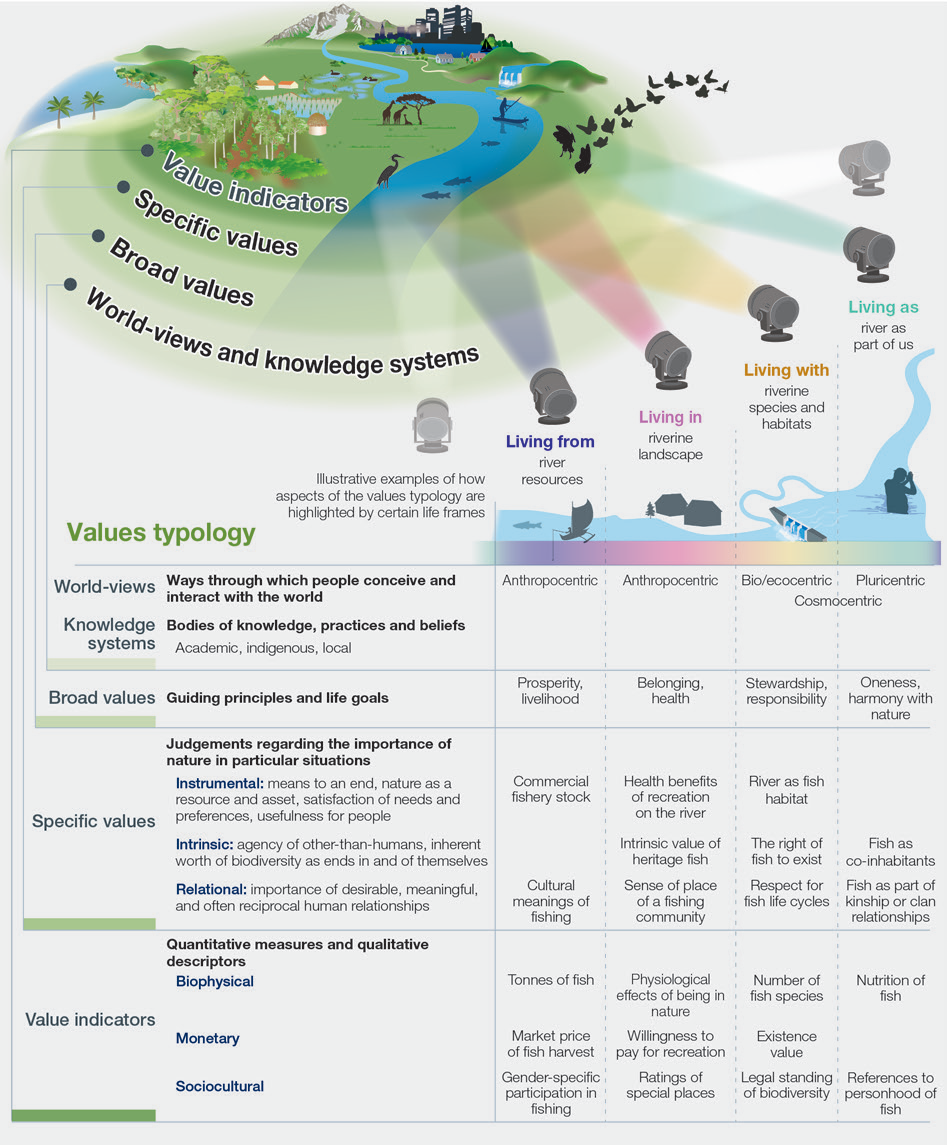

Precedents and Alternatives

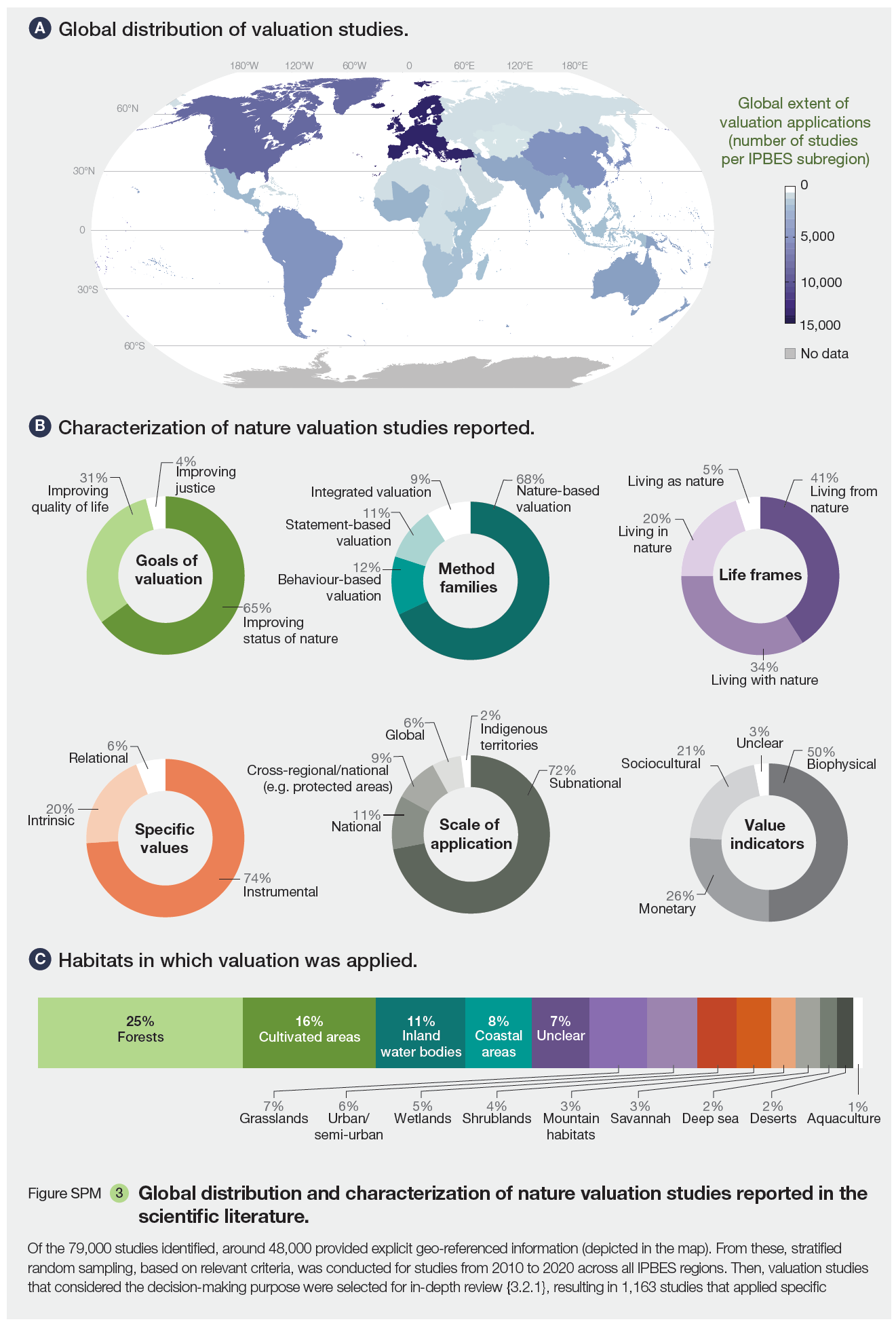

IBPES, Unai Pascual, Patricia Balvanera, Michael Christie, Brigitte Baptiste, David González-Jiménez, Christopher B. Anderson, et al. Summary for Policymakers of the Methodological Assessment of the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Bonn: Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, 2022.

Raymond, Christopher M., Christopher B. Anderson, Simone Athayde, Arild Vatn, Ariane M. Amin, Paola Arias-Arévalo, Michael Christie, et al. “An Inclusive Typology of Values for Navigating Transformations towards a Just and Sustainable Future.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 64 (2023): 101301. https://doi.org/10/gv8sv9.

References

Borthwick, Madeleine, Martin Tomitsch, and Melinda Gaughwin. “From Human-Centred to Life-Centred Design: Considering Environmental and Ethical Concerns in the Design of Interactive Products.” Journal of Responsible Technology 10 (2022): 100032. https://doi.org/10/gqgzfv.

On inclusion in design:

Hamraie, Aimi. Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Footnotes

Sherry R. Arnstein, "A Ladder of Citizen Participation," Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35, no. 4 (1969): 216–224.˄

Calzada, Igor. Smart City Citizenship. Waltham: Elsevier, 2020.˄

Nieuwenhuijsen, Mark, and Haneen Khreis, eds. Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning: A Framework. Cham: Springer, 2019.˄

Gokulan Theyyan, "Arnstein's Ladder of Citizen Participation: A Critical Discussion," Asian Academic Research Journal of Multidisciplinary 2, no. 7 (2015): 245.˄

Hou, Jeffrey. “Citizen Design: Participation and Beyond.” In Companion to Urban Design, edited by Tridib Banerjee and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, 329–40. London: Routledge, 2011.˄

Jonathan Quetzal Tritter and Alison McCallum, "The Snakes and Ladders of User Involvement: Moving beyond Arnstein," Health Policy 76 (2006).˄

Collins, Kevin, and Raymond Ison. 2006. “Dare We Jump off Arnstein’s Ladder? Social Learning as a New Policy Paradigm.” Proceedings of PATH (Participatory Approaches in Science & Technology) Conference (Edinburgh), 2006, 1–15.˄

Bratteteig, Tone, and Ina Wagner. Disentangling Participation: Power and Decision-Making in Participatory Design. Cham: Springer, 2014.˄

Carpenter, Nico. “Power as Participation’s Master Signifier.” In The Participatory Condition in the Digital Age, edited by Darin Barney, Gabriella Coleman, Christine Ross, Jonathan Sterne, Tamar Tembeck, Darin Barney, Gabriella Coleman, Christine Ross, Jonathan Sterne, and Tamar Tembeck, 3–19. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.˄

Keiron Bailey and Ted Grossardt, "The Arnstein Gap: Twenty Years On, What Has Changed?," in REAL CORP 2025 Proceedings, ed. M. Schrenk et al. (Vienna: REAL CORP, 2025).˄

Firchow, Pamina, and Yvette Selim. “Meaningful Engagement from the Bottom-up? Taking Stock of Participation in Transitional Justice Processes.” International Journal of Transitional Justice 16, no. 2 (2022): 187–203. https://doi.org/10/g7t2hg. Evrard, Elke, Gretel Mejía Bonifazi, and Tine Destrooper. “The Meaning of Participation in Transitional Justice: A Conceptual Proposal for Empirical Analysis.” International Journal of Transitional Justice 15, no. 2 (2021): 428–47. https://doi.org/10/gqdgf6.˄

Fung, Archon. 2006. “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance.” Public Administration Review 66 (s1): 66–75. https://doi.org/10/cwtd76.˄

Varwell, Simon. 2022. “A Literature Review of Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation: Lessons for Contemporary Student Engagement.” Exchanges: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal 10 (1): 108–44. https://doi.org/10/hbcjdc.˄

White, Marcus, and Nano Langenheim. 2021. “A Ladder-Truss of Citizen Participation: Re-Imagining Arnstein’s Ladder to Bridge between the Community and Sustainable Urban Design Outcomes.” Journal of Design Research 19 (1/2/3): 155. https://doi.org/10/hbcjfq.˄

Hurlbert, Margot, and Joyeeta Gupta. 2024. “The Split Ladder of Participation: A Literature Review and Dynamic Path Forward.” Environmental Science & Policy 157: 103773. https://doi.org/10/hbcjjf.˄

Hernandez-Santin, Cristina, Marco Amati, Sarah Bekessy, and Cheryl Desha. “Integrating Biodiversity as a Non-Human Stakeholder within Urban Development.” Landscape and Urban Planning 232 (2023): 104678. https://doi.org/10/grwwhh.˄

Mohedano Roldán, Alba, Andreas Duit, and Lisen Schultz. “Does Stakeholder Participation Increase the Legitimacy of Nature Reserves in Local Communities? Evidence from 92 Biosphere Reserves in 36 Countries.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21, no. 2 (2019): 188–203. https://doi.org/10/gjbtzj.˄

Kiss, Bernadett, Filka Sekulova, Kathrin Hörschelmann, Carl F. Salk, Wakana Takahashi, and Christine Wamsler. “Citizen Participation in the Governance of Nature-Based Solutions.” Environmental Policy and Governance 32, no. 3 (2022): 247–72. https://doi.org/10/gpsrkd.˄

Reed, Mark S. “Stakeholder Participation for Environmental Management: A Literature Review.” Biological Conservation 141, no. 10 (2008): 2417–31. https://doi.org/10/bvq7xj.˄

Frietsch, Marina, Manuel Pacheco-Romero, Vicky M. Temperton, Beth A. Kaplin, and Joern Fischer. 2024. “The Social–Ecological Ladder of Restoration Ambition.” Ambio 53 (9): 1251–61. https://doi.org/10/hbckr2.˄

Førde, Anniken, Tone K. Reiertsen, Cecilie Sachs Olsen, Ingeborg Solvang, and Helen F. Wilson. 2025. “The Ladder of Multispecies Participation: Moving towards a More Convivial Urban Planning.” Nordic Journal of Urban Studies 6 (1–2026): 1–18. https://doi.org/10/hbcksh.˄

Cloke, Paul, and Owain Jones. “Turning in the Graveyard: Trees and the Hybrid Geographies of Dwelling, Monitoring and Resistance in a Bristol Cemetery.” Cultural Geographies 11, no. 3 (2004): 313–41. https://doi.org/10/cvzrxd.˄

Backlinks