10 Narrativ

The Task

3 contrasting sections, what to vary

dynamic transitions scales

Aspects of Change

types of change (climate, weather, events) duration of change speed of change volume of change

change from the perspective of the participants

Examples

How should we assess a design project? This case uses Junya Ishigami’s Art Biotop Water Garden in Nasu, Japan to test critical questions.1,2

What it claims to be

Designers frame the project as a poetic synthesis of landscape history and delicate preservation.

Their narrative invokes a palimpsest: former rice paddies, a mossy forest, and meadow layered into a contemplative water–tree matrix.

They position:

- The relocation of 318 trees as rescue from clearing for adjacent development.

- The insertion of 160 shallow ponds as crafting an ecology of reflection, slowness, and immersion.

The project adopts rhetoric of care, precision, and persistent research: five years of modelling, observation, and spatial calibration. Its imagery, including mist, reflections, hovering trunks, soft moss, seeks a narrative of effortless naturalness, as if the site had tended toward this condition and design merely revealed it.

Awards,3 peer acclaim, stylised drawings, and highly curated photographs stabilise that narrative.

The project claims that it:

- preserves life

- honours site memory

- composes a living field of subtle atmospheric experience

- offers sustainable beauty

What it is

The project is a commercial hospitality venture.

Materially, it is an engineered composition that stages ecological subtlety while depending on intensive intervention. Builders uprooted, transported, replanted, and recomposed trees for spatial effect.

2018: a tree extracted for relocation. Root loss, soil disturbance, and rupture of underground communication networks occur. Image from PublicDelivery

The result: uniform, straight, branch-poor trunks revealing interior forest origin now exposed to wind stress.

Limited plant diversity, canopy layering, and understorey complexity remove habitat features.

Set into pits smaller than crown spreads and separated by impermeable barriers, trees cannot form the mycorrhizal and root networks that underpin resilience.

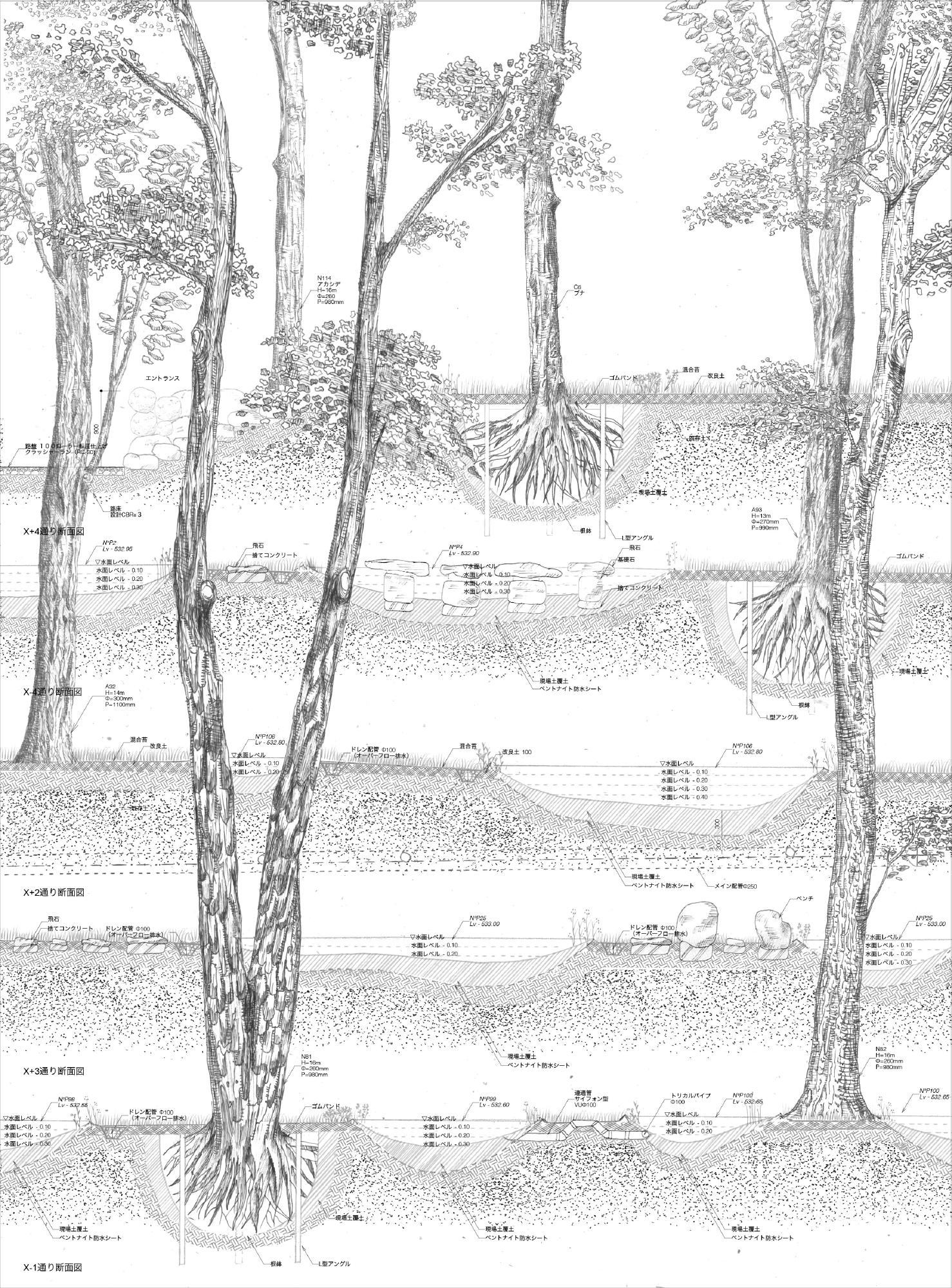

Small insulated root bowl; crown width usually mirrors root reach. Impermeable surfaces constrain exploration, communication, reproduction, and ecosystem service provision. Image by PublicDelivery

The water bodies are excavated, lined cavities enabling pond adjacency incompatible with the natural tolerances of the selected deciduous species (beech, oak, others).

Hydrological performance relies on controlled inflow via an existing sluice and irrigation infrastructure.

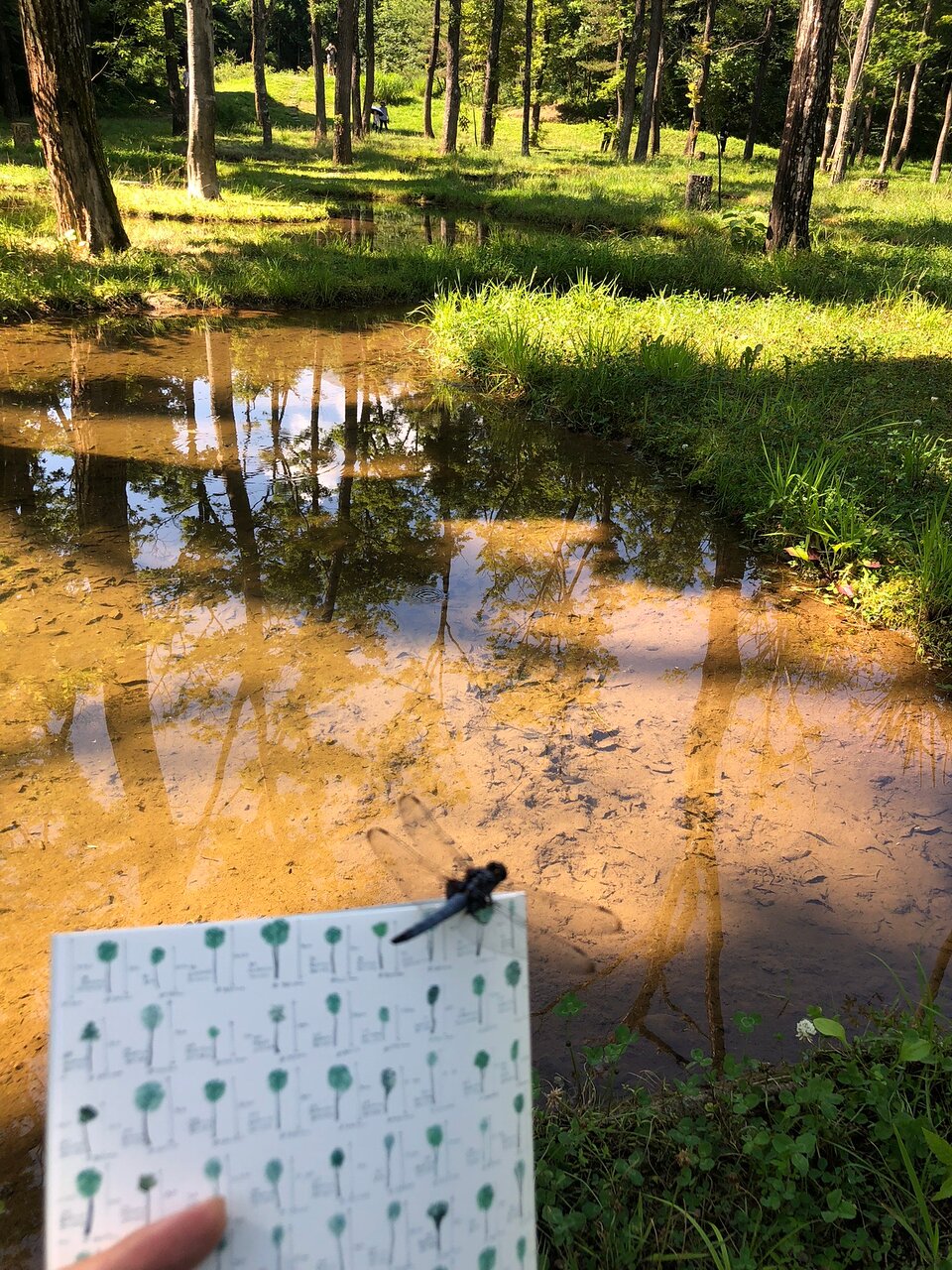

The moss layer proved fragile; visitor photographs (2020–2021) show patch loss, bare soil, algal or stagnant water, tree stress, mortality, stumps, exposed synthetic pond edges, and probable geotextile or polymer liners subject to degradation and microplastic persistence.

October 2020: moss largely gone; the water looks lifeless; stressed and dead trees. Visitor images

October 2020: background trees likely beyond the site perimeter. Visitor images

October 2020: continued decline. Visitor images

July 2021: tree removals visible as stumps. Visitor images

October 2020: exposed liner edges; likely limited-life polymer textiles, future microplastic sources. Visitor images

The claim of gentle preservation obscures resource expenditure (energy, materials, labour), ecological disruption (soil disturbance, altered microbial and root networks), and long-term maintenance burdens.

Ethically, questions arise around labour (reports of unpaid intern involvement), instrumental relocation of organisms for aesthetic capital, and absence of ecological monitoring or stewardship obligations.

Closure in 2023 contradicts the narrative of durable, evolving equilibrium.

The project operates more as a curated image of natural harmony than a resilient biophysical and social system.

It shows how narrative framing can displace scrutiny of environmental cost, decay, and injustice toward nonhuman lives.

Critical questions about design narratives

Outcomes were predictable. Was the project successful, and was it ethical?

Use this case to interrogate any design narrative:

Origin narrative

What story of the site is told, and what is omitted?

Example: rice paddy memory and forest preservation foregrounded; disruptive tree extraction and altered hydrology minimised.

Preservation claims

Is “saving” a net ecosystem gain or an aesthetic relocation?

Example: trees “saved” yet placed in an artificial hydric regime that induced stress and mortality.

Simulation vs authenticity

Are visual cues substituted for ecological function?

Example: mossy woodland atmosphere depends on liners enabling improbable pond–tree adjacency.

Temporal performance

Does the narrative admit possible decline or failure?

Example: images imply timeless calm; visitor photographs document degradation.

Hidden infrastructure

What enabling systems remain concealed?

Example: exposed edges show reliance on synthetic liners with finite life.

Maintenance economy

What labour and cost sustain the aesthetic?

Example: fragile moss and stressed trees imply intensive, undisclosed care.

Ecological metrics

Are biodiversity, soil health, water quality, or carbon impacts measured?

Example: compositional precision displaces reporting of outcomes.

Ethical labour relations

Were all contributors paid fairly?

Example: reports of unpaid interns conflict with claims of care.

Nonhuman agency

Are organisms partners or props?

Example: trees treated as modular spatial units, not living beings.

Resource footprint

What materials, energy, and emissions were required?

Example: “delicacy” rhetoric masks extractive inputs.

Reversibility and end-of-life

Can removal avoid persistent pollutants?

Example: polymer liners risk long-term microplastic dispersion.

Public accessibility and longevity

Who benefits, for how long, under what governance?

Example: closure undercuts claims of enduring cultural or ecological value.

Representation techniques

How do media exclude failure?

Example: professional imagery omits stumps, liner exposure, moss loss.

Success criteria

Is success equated with aesthetic reception?

Example: acclaim substitutes for environmental accountability.

Systematic questioning of this type can usefully separate narrative scaffolding from material, ecological, temporal, and ethical realities.

Benefitting from such separation, this case-study example shows how storytelling can aestheticise disturbance, stabilise an image of “light touch,” and defer scrutiny of maintenance, decline, and responsibility.

A focused analysis of outcomes can encourage higher quality project and better reflect needs, capacities, power, and site relationships or human and nonhuman stakeholders.

Further reading

On intellectual honesty and self-deception:

Frankfurt, Harry G. 2005. On Bullshit. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

On problems with creativity:

Schaefer, Stephan M., and Olof Hallonsten. 2024. “What’s Wrong with Creativity?” Organization 31 (5): 820–28. https://doi.org/10/gsdfmf.

Better alternatives

Better alternatives include Miyawaki mini forests (also from Japan) and other methods that restore or create ecosystems with lower intervention and higher self-sustainability.

Further reading

Miyawaki forests background:

Lewis, Hannah, and Paul Hawken. 2022. Mini-Forest Revolution: Using the Miyawaki Method to Rapidly Rewild the World. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Comparative urban and peri-urban ecosystems:

McDonnell, Mark, Amy Hahs, and Jürgen H. Breuste. 2009. Ecology of Cities and Towns: A Comparative Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Footnotes

Winner of the €100,000 Obel Award; the commissioned report is not publicly available.˄