More-than-Human Explorations

Objectives

What should change after the "exploration" has completed? For whom and how?

Worldview

The exchange so far highlighted the tension between the world "out there" and the traversable datasets.

I think it would be interesting to acknowledge that many entities, including nonliving systems, are storing and processing information away from any human-constructed datasets as well as when interfacing with them. Recent discussions based on scientific advances lean toward literal agreement with panpsychism (this is likely beyond scope but I think significant as a possibility).4

For example, dunes or river channels are memories (databanks) of past events. So are animal paths. Cf. cognitive ecology, sensory ecology, biosemiotics, ecology of fear,7 etc. Information acquisition, storage, processing, and interpretation often (always) happen across systems, including across cells, tissues, organs, organisms, species, families, communities, etc. For example, a bird calls and a ground predator knows to look for it as it is juicy, or to be cautious of the venomous snake the bird announces, etc.

This is directly related to the information processing capabilities, including volumes of data, speed of processing in multilevel interpretative systems (flatter systems in reptiles or amphibians versus more hierarchical ones in mammals (see Example 1), etc.).

The outcome of this is the impact on collective decision-making and thus on design.8

Example 1

Here is a clear example of what I mean:

Male frogs gather in large, noisy groups to call for mates. This creates a problem: the same calls that attract females could also attract predators like bats. So, frogs have evolved to exploit the time a mammalian brain takes to process sound to achieve more sophisticated integration of inputs that also include vision, olfaction, etc. (humans have, what, 35 senses?) Mammals run incoming vibrations through sophisticated neural circuits. Frogs have a simpler system with ears that are internally connected, creating a basic pressure-difference detector. The overlapping calls by frogs can be perceived by frogs as they process the information faster but not by bats who take longer.5 Frogs have evolved to occupy a favourable information-processing niche: they communicate in a way that their intended receivers (other frogs) can decode, but their predators (mammals) cannot. Such "precedent effects" are common in resolving competition for location and perception.6

Example 2

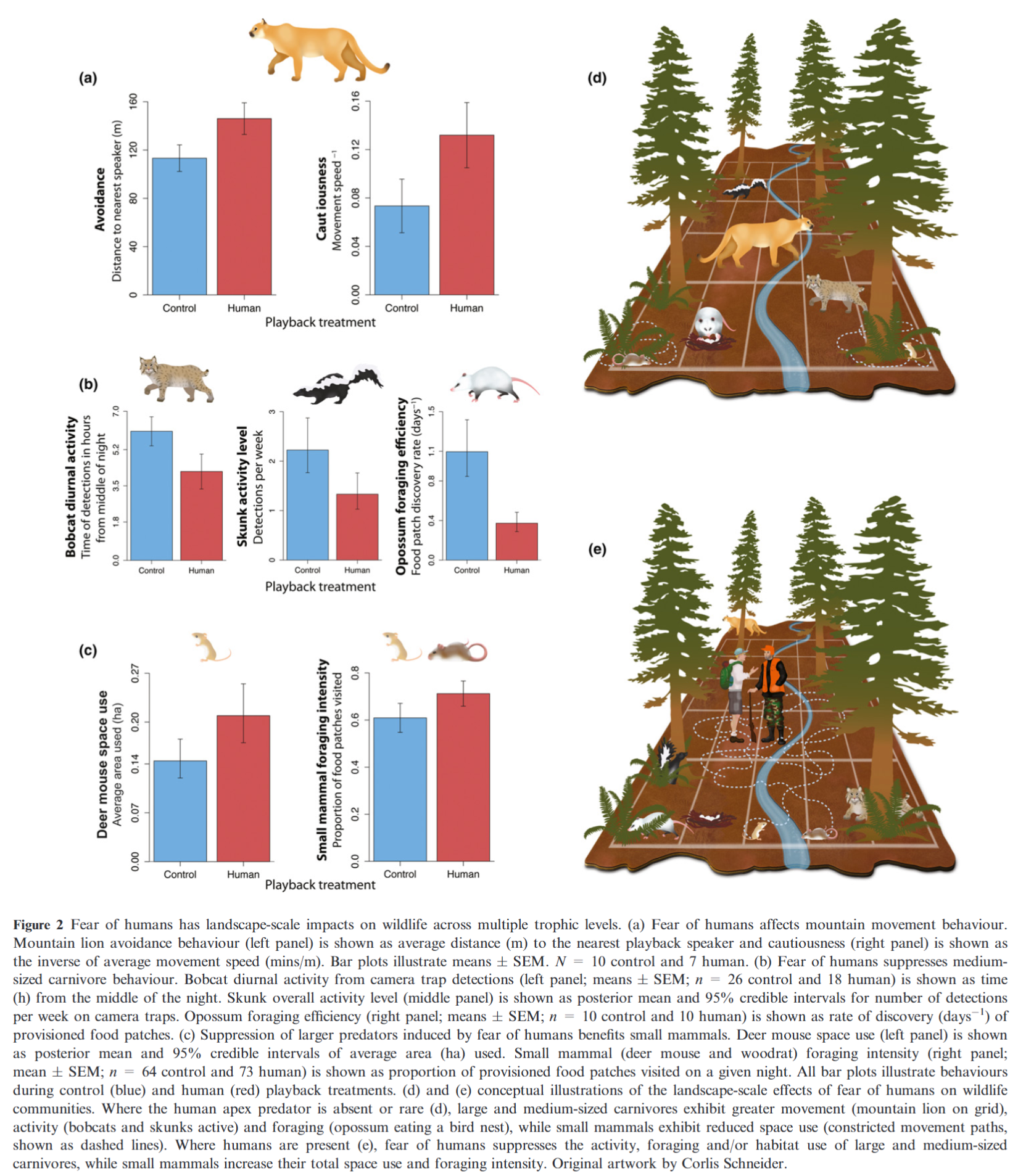

Here is another example of human impact on fear landscapes:

Suraci, Justin P., Michael Clinchy, Liana Y. Zanette, and Christopher C. Wilmers. “Fear of Humans as Apex Predators Has Landscape-Scale Impacts from Mountain Lions to Mice.” Ecology Letters 22, no. 10 (2019): 1578–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13344.

Tensions and Challenges

- Presence of different interpreters (with different capabilities, biases, needs, etc.). Maybe our take on the "capabilities" approach is useful to think with about concrete nonhuman agents.3

- Human actions distorting, discounting, disconnecting nonhuman information processing and actions

- Human biases in attention, data collection, interpretation (anthropocentrism, speciesism, see the concept of bias, evidence of human bias)

- Ethical challenges of representing nonhuman entities (privacy, fuzzy boundaries, lack of consent, lack of an ideal state)

Possible Activities

- Simulate. Probe and perform information processing nodes (beings, communities): capabilities, speed of processing, data input, limits on actions. Cf. cardboard computing approaches, performances, games.

- Remodel. Re-describe or prototype known entities (attitudes, objects, interactions, places) from the perspective of various information processors (animals, plants, rivers, dunes, weather systems, etc.). Maybe our "learning with owls" effort is relevant, it involved walking.2

- Deliberate. Can participants or groups represent nonhuman individuals or aggregate personas and them come into negotiation with other such entities?

- Empower. Look for "weak signals" and see if they can be amplified to have a greater effect on the social or ecological systems. Prototype interventions. Maybe our ladder/stair could be handy?1

- Meet. Can we bring an actual living nonhuman being into this "exploration" or consider what it would take to do that in the future?

Footnotes

Fields, Chris, and Michael Levin. “Life, Its Origin, and Its Distribution: A Perspective from the Conway-Kochen Theorem and the Free Energy Principle.” Communicative & Integrative Biology 18, no. 1 (2025): 2466017. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2025.2466017.˄

Zanette, Liana Y., and Michael Clinchy. “Ecology of Fear.” Current Biology 29, no. 9 (2019): R309–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.042.˄

Roudavski, Stanislav, and Douglas Brock. “From Dingoes to AI: Who Makes Decisions in More-than-Human Worlds?” TRACE ∴ Journal for Human-Animal Studies 11 (2025): 56–96. https://doi.org/10.23984/fjhas.145720.˄

Jones, Douglas L., and Rama Ratnam. “Are Frog Calls Relatively Difficult to Locate by Mammalian Predators?” Journal of Comparative Physiology A 209, no. 1 (2023): 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-022-01594-7.˄

Litovsky, Ruth Y., H. Steven Colburn, William A. Yost, and Sandra J. Guzman. “The Precedence Effect.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 106, no. 4 (1999): 1633–54. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.427914.˄

Parker, Dan, Kylie Soanes, and Stanislav Roudavski. “Interspecies Cultures and Future Design.” Transpositiones 1, no. 1 (2022): 183–236. https://doi.org/10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.183.˄

Parker, Dan, Kylie Soanes, and Stanislav Roudavski. “Learning with Owls: Human–Wildlife Coexistence as a Guide for Urban Design.” People and Nature 7, no. 7 (2025): 1619–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70067.˄

Roudavski, Stanislav. “The Ladder of More-than-Human Participation: A Framework for Inclusive Design.” Cultural Science 14, no. 1 (2024): 110–19. https://doi.org/10.2478/csj-2024-0015.˄