Budj Bim

This note is about the UNESCO World Heritage site of Budj Bim, in south-western Victoria, Australia.

"The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape was continuously inhabited by the Gunditjmara after the eruptions of Mt. Eccles and Mt. Napier (c. 18,000–28,000 BC) and during the subsequent formation of Lake Condah around 9000–6000 BC (Builth et al. 2008; Rose et al. 2016, pp. 590–592). The Gunditjmara constructed closely grouped dry-stone houses from basalt rocks and inhabited them on a permanent to semipermanent basis (Clark 1991). Population levels were high, and the eel fishery provided an abundant source of food that may have also been smoked for storage (Builth 2002; Builth et al. 2008; Clark 1991). According to Wettenhall with the Gunditjmara (2010; see also Rose et al. 2016, p. 592), eels were a valuable trade commodity at large, intergroup meetings (up to 1000 people). Ethnohistorical observations at European contact record an economy based on complex exchange systems (Builth 2002, p. 7; Lourandos 1980a, b, 1991).

The enormous landscape modification at Budj Bim resulted in artificial spatial expansion and temporal extension of wetland ecosystems (Builth 2014; McNiven et al. 2012, pp. 44–45). This wetland enhancement regulated and augmented eel production by allowing juvenile eels (elvers) the physical means to reach suitable, expanded wetland habitats and, as eels are catadromous fish, also allowed the means to return to the ocean to spawn (Builth 2016, pp. 12, 16). Once in the system, young shortfin eels were contained and grown in anthropogenically modified waterbodies, creating a long- and short-term eel fishery where the management of elvers was an investment in their future production. Furthermore, suitable expanded environmental conditions ensured greater numbers of adults for spawning (Builth 2016, p. 12; McNiven et al. 2012, pp. 44–45). As this system involved controlling a part of the eel life cycle (movement of juveniles into captive environment), it is classified as domestication level 2. This system not only ensured perennial availability of younger eels, but habitat expansion would also have ensured greater availability of other wetland resources including freshwater fish, such as tupong (Pseudaphritis urvillii) and common galaxias (Galaxias maculatus), and swamp vegetation, such as tubers, corms, and roots of reeds, beyond their normal seasons (Builth 2016, pp. 4–5; Builth et al. 2008, p. 414; Rose et al. 2016). Builth et al. (2008, p. 414) also suggested that the extensive system of channels would have “…countered rainfall variability by facilitating controlled drainage in periods of heavy rainfall and retaining water during dry periods. The system would have therefore contributed to the stability of the economy and population.” In addition, downstream migrating eels in autumn would have been highly nutritious, containing at least 55% greater fat content compared to feeding eels (Builth 2016, p. 11). This anthropogenic system facilitated the easy capture of shortfin eels (juveniles and adults) throughout the year (Builth 2016, pp. 4–5, 16; Builth et al. 2008, p. 414; McNiven and Bell 2010; Rose et al. 2016)."

From:

Rogers, Ashleigh J. “Aquaculture in the Ancient World: Ecosystem Engineering, Domesticated Landscapes, and the First Blue Revolution.” Journal of Archaeological Research 32, no. 3 (2024): 427–91. https://doi.org/10/gstp97.

References

Jackson, Sue. “Caring for Waterscapes in the Anthropocene: Heritage-Making at Budj Bim, Victoria, Australia.” Environment and History 29, no. 4 (2023): 591–611. https://doi.org/10/g93qpk.

Koster, Wayne, Ben Church, David Crook, David Dawson, Ben Fanson, Justin O’Connor, and Ivor Stuart. “Factors Influencing Migration of Short-Finned Eels (Anguilla Australis) over 3 Years from a Wetland System, Lake Condah, South-East Australia, Downstream to the Sea.” Journal of Fish Biology 104, no. 6 (2024): 1824–35. https://doi.org/10/g93qq2.

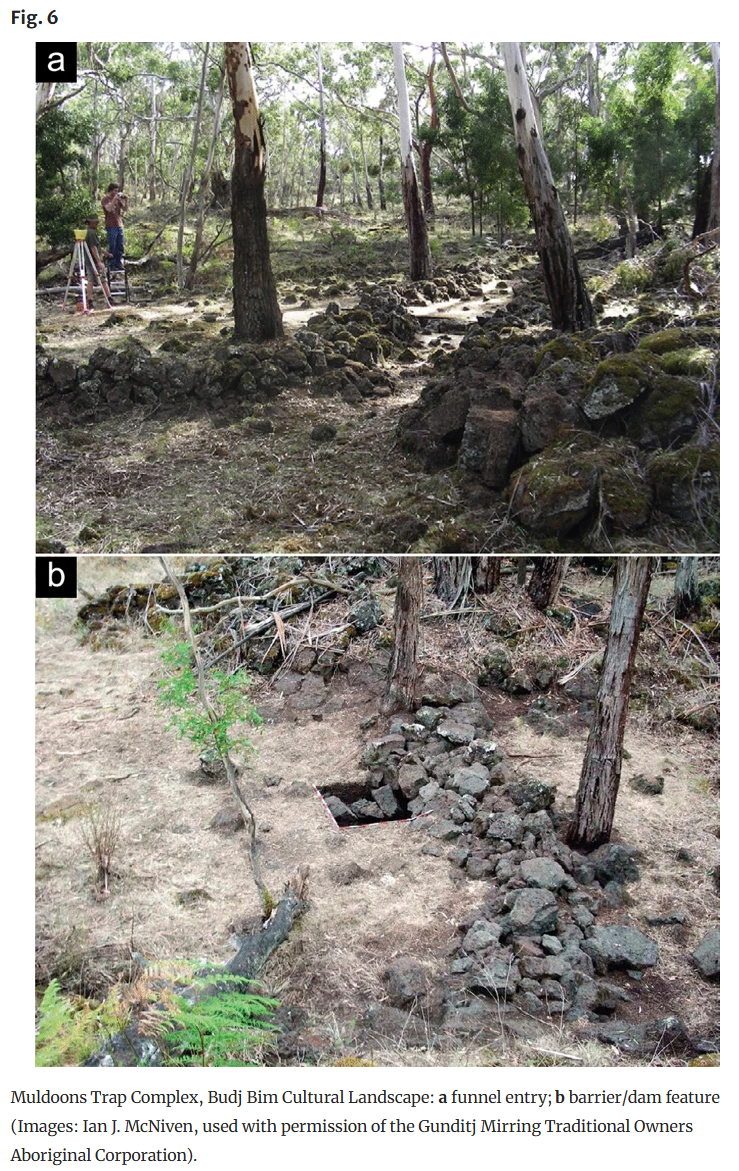

McNiven, Ian, Joe Crouch, Thomas Richards, Kale Sniderman, Nic Dolby, and Gunditj Mirring. “Phased Redevelopment of an Ancient Gunditjmara Fish Trap over the Past 800 Years: Muldoons Trap Complex, Lake Condah, Southwestern Victoria.” Australian Archaeology 81, no. 1 (2015): 44–58. https://doi.org/10/grxv7b.

Stuart, Ivor G., Timothy J. Marsden, Matthew J. Jones, Matt T. Moore, and Lee J. Baumgartner. “Rock Fishways: Natural Designs for an Engineered World.” Ecological Engineering 206 (2024): 107317. https://doi.org/10/g93qq4.